Fonograf Editions, 2025, 184 pp.

Forty years after he said he had stopped writing poems, thirty after his death, and a decade after the first book-length English translation of his work appeared, Jaime Gil de Biedma (1929-1990) finally had his pop culture moment: The Consul of Sodom, a 2009 movie based on his life, which was nominated for Spanish awards, praised by Spanish critics, and denounced as luridly hypersexual by the Spanish novelist Juan Marsé—who was also portrayed in it. And no wonder: Gil de Biedma led a life—or perhaps a few lives—that seems made for a sexy movie, one you could only shoot, produce, and distribute in a society where queerness is no longer condemned.

Gil de Biedma neither grew up nor wrote his greatest poems in such a society. Raised in Barcelona, well-off thanks to his tobacco-importing family, the poet studied in Oxford, then kept his adult life divided: between his left-ish literary allies, who risked persecution under Francisco Franco’s regime, and the buttoned-up needs of his family business, where he became an executive; between Barcelona, with its Gauche Divine, and Manila, with its Anglophone elite; between the reflective knowingness he shared with his beloved Eliot and Auden and the passionate, homoerotic nostalgia—“O for a youth of sensations rather than thoughts!”—that no one in English or Spanish had yet carried off so well (though he might have found models in Proust).

Postwar Spain gave Gil de Biedma ways to imagine joy, though he had to imagine himself as immature, childish, or incomplete in order to do it: Adulthood meant sadness, suits, and straight, bourgeois rules. “Even the air in those days,” as James Nolan puts it in translation, “seemed / somehow arrested” (“estuviera suspenso”), as in “arrested development”; songs from far away had to bring him “the white heat that breaks your heart” (“la intensidad que aflige al corazón”). No wonder he imagined, or relived, or built for himself, a gay adolescence.

For an effete aesthete, he wore his heart on his silky short sleeve. Even the poem titles show what he wanted to do—how much he pursued, and cherished, and embodied, and regretted that double sensibility: “Mañana de ayer, de hoy” (yesterday’s tomorrow, today); “Un cuerpo es el mejor amigo de hombre” (the body is a man’s best friend); “Himno a la juventud” (hymn to youth); “No volveré a ser joven” (I’ll never be young again). The same poet who wanted to live as if he could stay out all night, as if he could revel forever in the moment, with pleasures both innocent and sexual—the scent of poplars, poolside nudity, more—also kept seeing his life as already over, a ghost looking back on how good he had it, how good we all have it. His strongest work can feel like the last act of Our Town put into Spanish, if the last act of Our Town included reflections on gorgeous blowjobs.

Gil de Biedma’s eroticized, deeply felt, as-if-posthumous views start early, with the “aparecidos” (apparitions; ghosts) and “desenterrados vivos” (people disinterred, or un-buried, alive) in his first mature book, Compañeros de Viaje (Fellow Travelers) published in 1959: They’re people unable to live their full lives, thanks to ill luck, or to what we now call the closet, or to the repressive atmosphere of Franco’s Spain. In them, Gil de Biedma recognized parts of himself, never more so than in the great and avowedly posthumous poems of his last writing years, collected in 1968’s Poemas Pósthumos, published (despite the title) very much during the poet’s lifetime: “Después de la Muerte de Jaime Gil de Biedma” (after the death of Jaime Gil de Biedma), “Contra Jaime Gil de Biedma” (against Jaime Gil de Biedma), “Amor más poderoso que la vida” (love stronger than life). The second edition of his collected poems, published in 1982, concluded with an almost flirtatious “autobiographical note” explaining why he had stopped writing: “I believed that I wanted to be the poet but really” (al fondo) “I wanted to be the poem. And in a way, in the worst way, I did it” (lo he conseguido).

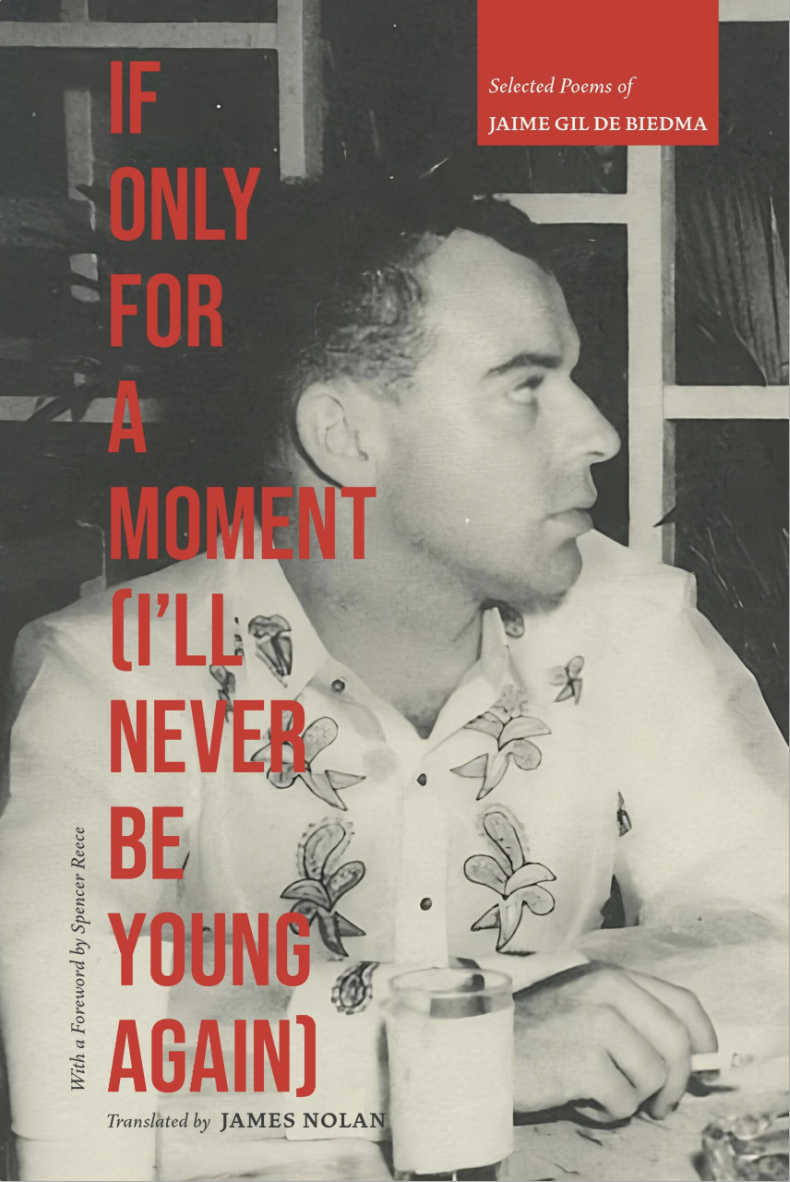

All but two of the poems I’ve named so far appear—along with the poet’s note—in reliable, conversational translations in what seems to be the first and only book of Gil de Biedma’s work in English: Nolan’s If Only for a Moment (I’ll Never Be Young Again). The book first came out in 1993 from City Lights under the title Longing; Fonograf has retitled and republished it, with a new preface by Spencer Reece.

Nolan’s foreword and afterword get the poet right: a figure of strong emotion who made his own “dramatic masks”; an Anglophile in nationalist, Catholic Spain; “Prufrock waking up with a hangover” (presumably in bed with a man); a figure of multiplicity, a set of “friends you only know through their images in mirrors.” Nolan understandably focuses on the longer poems and on the ones in free verse. The quatrains, and the exemplary political sestina “Apología y Petición,” require (as Nolan says) another kind of hand.

The work Nolan did choose to translate benefits both from his light touch and from the book’s en face originals. Take, almost at random, the “figuras diminutas / que se quedan atrás para siempre, en la memoria, / como peones camineros”—“tiny figures / left behind in memory forever / like men working on the road.” Nolan gets the conversational cadence, the breathy ending on the penultimate line, the hard stop at the English end. I like it. I also notice that “peones” have become not peons or navvies or hard-hats or laborers or road workers (or pawns, as in chess) but just men. Nolan consistently makes the humanizing, the demotic, perhaps even the American, choice: It’s as if Gil de Biedma’s attitudes made him seem artificial enough, precious enough, and the translator means to bring him closer to us.

Nolan’s style fits the kinds of nostalgia, at once elevated and intimate, that brought me to Gil de Biedma’s side and made me love him as soon as I found him, three decades ago, in J. M. Cohen’s Penguin Book of Spanish Verse—on the one hand, a writerly mind that could not stop reflecting on its reflections; on the other, a heart that wants to keep dancing like we’re twenty-two (or eighteen). I found in him, too, a poet fleeing from a haute bourgeoisie he never disowned; a poet aspirationally international, and yet still tied to the weird leafy place of his birth (in his case: Barcelona; in mine: the white-dominated, private-school layer of Washington, D.C.). No wonder when I first read him I felt so seen. No wonder I couldn’t stop adapting, or quasi-translating, or something, his work into versions that reflected not his experience but my own: a child of privilege, half-closeted, who never had the chance to live as a girl, to go through endless best-friend breakups in sparkly handwritten notes, cast endless spells with Barbies, or lose my first sleepover-love to the relentless approach of heterosexuality, which (of course) would pass me by.

Sometimes you find a writer, in another language, who just understands you in ways that you don’t understand yourself: That’s what happened to Gil de Biedma and me, or maybe to Gil de Biedma’s personae and me. He called his collected poems Las Personas del Verbo, which is a pun: “the persons of the verb,” as in first, second, third person—tengo, tienes, tiene, and so on—but also “the people of the verb,” the affiliates of action, and “the masks of the word,” since persona in Latin means mask, and “the people of the word,” we literary types, who no sooner act than write, who kiss and tell. In these personae, I found—in Spanish, with almost no gendered pronouns to spoil them—the poems that Celia might have written to Rosalind, some at the time, some decades afterwards, unbothered by Oliver, bothered a little by Orlando, with Barcelona as the Forest of Arden.

It probably helped that when I found him, he and I were both living effortfully international lives—me, happily half-in, half-out of the closet in Oxford, discovering among British and Irish poets a scene more congenial than what the late poetry wars—all heart or all brain, rarely both—had offered my tiny, white slice of America. And it certainly helped that I wasn’t sure if I was really, or could ever become, a girl: me but not me, a mind and a body at odds, believing my deepest yearnings impossible to justify or explain.

I did not make, or claim to make, accurate translations, having neither the wish nor the skill. Instead, imitating the writers from Chaucer to Merwin who imitated the writers they read, I incorporated slices and reactions to his poetry into my own, starting with my first published poems, taking shelter under the label “after,” and tagging Gil de Biedma by name. Here’s part of “Despues de la muerte de Jaime Gil de Biedma” from Poemas Pósthumos:

Agosto el jardín, a pleno día.

Vasos de vino blanco

dejados en la hierba, cerca de la piscina,

calor bajo los árboles. Y voces

que grita nombres.

Ángel,

Juan. María Rosa. Marcelino. Joaquina

—Joaquina de pechitos de manzana.

Tú volverias riendo del teléfono

anunciano más gente que venía:

te recuerdo correr,

la apagada explosion de tu cuerpo en el agua.

Here’s Nolan, with no concern except getting it right:

Glasses of white wine,

left in the grass near the pool,

heat under the trees. And voices

shouting names.

Ángel,

Juan. María Rosa. Marcelino. Joaquina—

Joaquina with the little apple breasts.

You come laughing from the phone,

announcing more people on the way.

I remember you running,

the dull plop of your body into the water.

Here’s what I did with the same passages, in 1995, complete with deliberate calques and intentional phonetic mistranslations:

It’s your garden. It’s August. Wine in vases,

tipsy incursions into your swimming pool,

soft heat under the trees. Voices bring

names: Angel, Juan, Marcelino, Maria

Rosa, Joaquina — Joaquina first of all,

the girl with the whispery, almost-invisible breasts.

The telephone laughed and you came back outdoors

and more of us, you said, would be on their way.

I remember, then, your one-yard run,

the flash of your body exploding into the water.

And here is a memorial for the man who hosted the actual party, at an actual swimming pool in northwest D.C., that I had in mind: the most complete hedonist I ever met, and the first out bisexual, and part of my first threesome (I don’t think he’d mind my sharing that detail). He later became an exemplary bicycling activist. I wish I had shown him the poem.

Without that bicycle activist’s real-life example, I’m not sure how long it would have taken me to even consider kissing boys—which, as it turned out, wasn’t my thing—but I did need to run the experiment to discover I wasn’t straight. Sometimes you have to try on ways of life, personae, scary new worlds, in order to learn which ones work for you. In almost the same way—maybe in just the same way—without the literary example of Gil de Biedma, I do not know if I would have kept on writing poems. Nor do I know how long it would have taken me to figure out that I’m really a girl. The personae, the pleasures, the double lives, and the regrets in his poems really do seem, to me, that powerful—at least if you’re coming (as I was and am) from another speech community, another poetic tradition. I wonder if he himself felt that way about Auden.

Was Gil de Biedma trans? No more so than Merrill or Auden. Was he a Gen Xer who grew up near I-95 and spent (I won’t say wasted) his high school years on a TV quiz show team? Again, no way. Nor did I grow up under a dictator, though I may well die under one. Did his reflections on divided identity, on the allure of bodies and verdant nights, on parties he’d never attended or would never attend again, on swimming with friends who might have been lovers, speak to a trans girl’s sense of her own developing or perhaps never-to-develop body? Fuck yes. Yes way. No poet I had read up to that point—not even Randall Jarrell (and I wrote a book about him)—spoke more deeply, or more often, to those particular slices of my wishes and my memories. I have no idea how many other people—maybe none! maybe five dozen!—found Gil de Biedma in that way. I do know that he’s admired in Spain as a bridge to modern queer writing, as a model for the young (the province of Segovia gives one young poet a prize each year in his name), as a way to pursue the artfulness of art.

Nolan’s preface says he moved to Spain in the late 1970s to translate Federico García Lorca, but then discovered in Gil de Biedma an urbane figure closer to his own heart—an alternative to Lorca’s mythic, ruralist Other: a sentimental poet, in Schiller’s sense, rather than a naïve one (though Nolan doesn’t use those terms). A naïve poet is nature, and speaks for nature; sentimental poets (in Schiller’s sense) speak to nature, and search for lost nature, either across woods and seas or within themselves. Those of us who read poetry mostly in English don’t need many more naïve poets; nor do we need another mythic pagan figure we can never recapture. We don’t need more Lorca, or even much more Neruda. We—at least I, and the poets closest to me—need models for our divided, practical, yearning, all too well-read selves. Gil de Biedma gave me that model, and he’ll go on doing as much, even after the republishing and remarketing of this faithful, accessible, demotic, and as gay as anything (just remember to use your own pronouns) translation. The future, long after (so to speak) the literal death of Jaime Gil de Biedma, could not ask for anything more.

✶✶✶✶

Stephanie Burt is Donald and Katherine Loker professor of English at Harvard. Her latest book of poetry is We Are Mermaids; new critical books include the anthology-with-essays Super Gay Poems, out now, and a book about Taylor Swift, out in Oct. 2025.

✶

Whenever possible, we link book titles to Bookshop, an independent bookselling site. As a Bookshop affiliate, Another Chicago Magazine earns a small percentage from qualifying purchases.