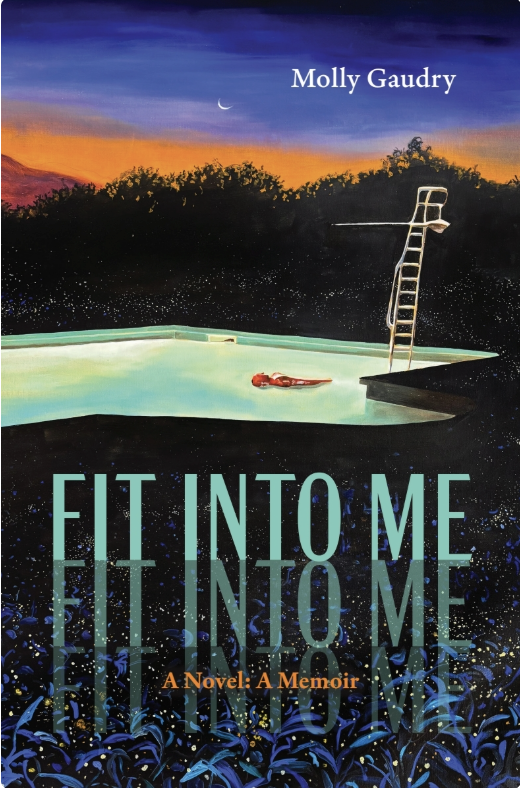

“Fit Into Me,” Rose Metal Press, 2025, 208 pp.

Abandon your expectations of both fiction and nonfiction. In Fit Into Me: A Memoir: A Novel, poet and author Molly Gaudry’s signature hybridity is boldly on display. She draws no linear lines in her work. Told in lyrical fragments, the book oscillates between the fictional story of a woman who must uphold the family teahouse business and Gaudry’s memoir—of her recovery from a traumatic brain injury and of entering a Midwestern American family as a three-year-old transnational Korean adoptee. Fit Into Me is not a traditional novel or memoir; it’s not even both of these things simultaneously. It’s formally inventive and lyrically written throughout the entirety of the text. Gaudry has created a satisfying and creative puzzle, an opportunity to look deeply and read slowly.

Gaudry’s verse novel, We Take Me Apart (Ampersand Books), used fairytale and poetic lyricism to explore mother-daughter relationships and was a finalist for the Asian American Literary Award and shortlisted for the PEN/Joyce Osterweil Award for Poetry. Her next book, Desire: A Haunting (Ampersand Books), continued her formally inventive style, exploring magical connections between spirits, both animal and human, as well as living and dead. Gaudry’s ruminations on what it means to long for connections with family and lovers continue to evolve in Fit Into Me. Though the three books may be read in any order, Gaudry’s body of work builds on itself, forming new connections and pathways upon further readings.

Identity and estrangement are focal points for Gaudry. In the memoir portion, she wrestles with adopted family, biological family, and the racial implications of being Korean yet estranged from her heritage. Similarly, the fictional portion’s protagonist—referred to as the “Tea House Woman”—must grapple with how to exist as an individual, instead of only in her role as a daughter. The Tea House Woman is estranged from her dreams and her own self, defined solely by family: “[S]he was seventeen years old, only a week away from turning eighteen and becoming a tea house woman—the tea house woman.”

Consider the contrast here between Gaudry and the Tea House Woman as daughters. For Gaudry, her traditional role as biological daughter is denied. For the Tea House Woman, there is an all-consuming imagining of such a role. It smothers individualism even as it enhances identity through collectivism. The choice to place this fictional narrative alongside her memoir showcases the conflict between a life we build and a legacy we inherit. Gaudry asks us to understand the complications, but refrains from offering conclusions—a strategy that pulls us closer to both narratives.

The title comes from Margaret Atwood’s poem “You Fit Into Me,” a borrowed line that helps Gaudry translate her own feelings. The phrase “fit into me” can act as both a plea and a demand, asking us to place ourselves inside the characters—but borrowed language can also act like a mirror, reflecting our own experiences back at us rather than revealing hers. Atwood’s poem brutally describes “a fish hook / an open eye,” blindness at the point of union. The “fit” is not meant to be romantic; it is meant to be dangerous.

Distancing and loneliness are another way the nonfiction and fiction portions use Atwood’s fish hook/open eye to mirror one another. Although the Tea House Woman takes lovers, she is emotionally removed. The lovers seem more like a projection of desire than fully realized characters. Similarly, Gaudry notes her own difficulty allowing emotional intimacy with her partners. In one example, the Tea House Woman’s Portuguese lover is the same as Gaudry’s lover, or perhaps nothing like Gaudry’s lover: “I would turn him [Gaudry’s lover] into the Portuguese lover, but the Portuguese lover is a fiction. Everything about the Portuguese lover is a fiction.” This oscillation in Gaudry’s prose leads us into her intimate world only to destroy our vision of it once again. It functions as a reminder that we are engaging with her art, not her personally. Art is a distinct category, an abstract piece.

Gaudry draws on the words of others to exemplify that language is a borrowed concept, a way to translate the self by fitting into another person’s words. When Gaudry arrived in the United States, she did not speak English; English is something from outside of the self that was imposed on her, a tool to make meaning of her experiences. At times, these sections are so beautiful that readers may realize they’ve lost their narrator, adrift in the language of others. Gaudry describes her process: “The other writer’s words are there, guiding, encouraging, leading the way. The result is both a strange new thing and an extended ode.” This device also serves as a protection against exploiting the self, a filter to avoid baring too much. By using the borrowed words of others, Gaudry reminds us of the universal within the specific. We can relate to her and to this chorus of voices that connect us all despite being strangers. Other writers’ voices are poignant, tiny word snapshots.

Gaudry’s signature move is to take us on detours, distracting us before we can stare too long at any one spot. Consider Gaudry’s brief comment: “Because when I was nine years old my parents adopted another little girl from Korea, six years old. Because I think she only lived with us for three years? Because I can’t remember, and I don’t ask—we don’t talk about her.” The topic is dropped and we are not invited in for any more memories of this temporary sister. We can only speculate as to what this experience meant to Molly or how it may have impacted her family unit. This strategy maintains the formal structure and the emotionally evasive tone, but it’s a detail of her memoir that feels underdeveloped. It is a crucial piece of her family puzzle that is relegated to a brief note.

The book carries a momentum that is equally built on structure and narrative, despite this blind spot. The text begins in small paragraphs, sometimes only single sentences left to stand alone. Some pages are populated in quotations floating as paragraphs. The subject content changes back and forth in confusion. Later, continuous unbroken paragraphs span pages as Gaudry recounts a roller skating accident that left her with a concussion, which impacted her vision and abilities to read and write. Her words begin to dominate, replacing the pages full of quotations. Subjects are held for longer spans.

We are shown what it is to read and comprehend in fragments and make sense of the pieces. Then, we glide toward recovery. Led back into these stories, flushed out so that what was murky becomes clear. Gaudry writes, “I might have simply suggested that the hybrid forms I specialized in reflected back the mixed and multiple identities of my own lived experiences, my students’, and when you really thought about it just about everyone’s.”

In Fit Into Me, Gaudry’s technique lures in her reader, offering fierce vulnerability, only to pivot into avoidance, reminding the reader that they will never quite know her. Consider the moment she recalls sentimental items given to her from her biological family: “In my hand,” she writes, “a delicate gold necklace with a tiny diamond pendant, which, unlike the leather skirt, I do still have. (Actually, that’s a lie. I lost the necklace, too, but it’s horrible to admit).” Gaudry pulls the reader closer, then let’s go, denying the emotions she brought forward once again.

✶✶✶✶

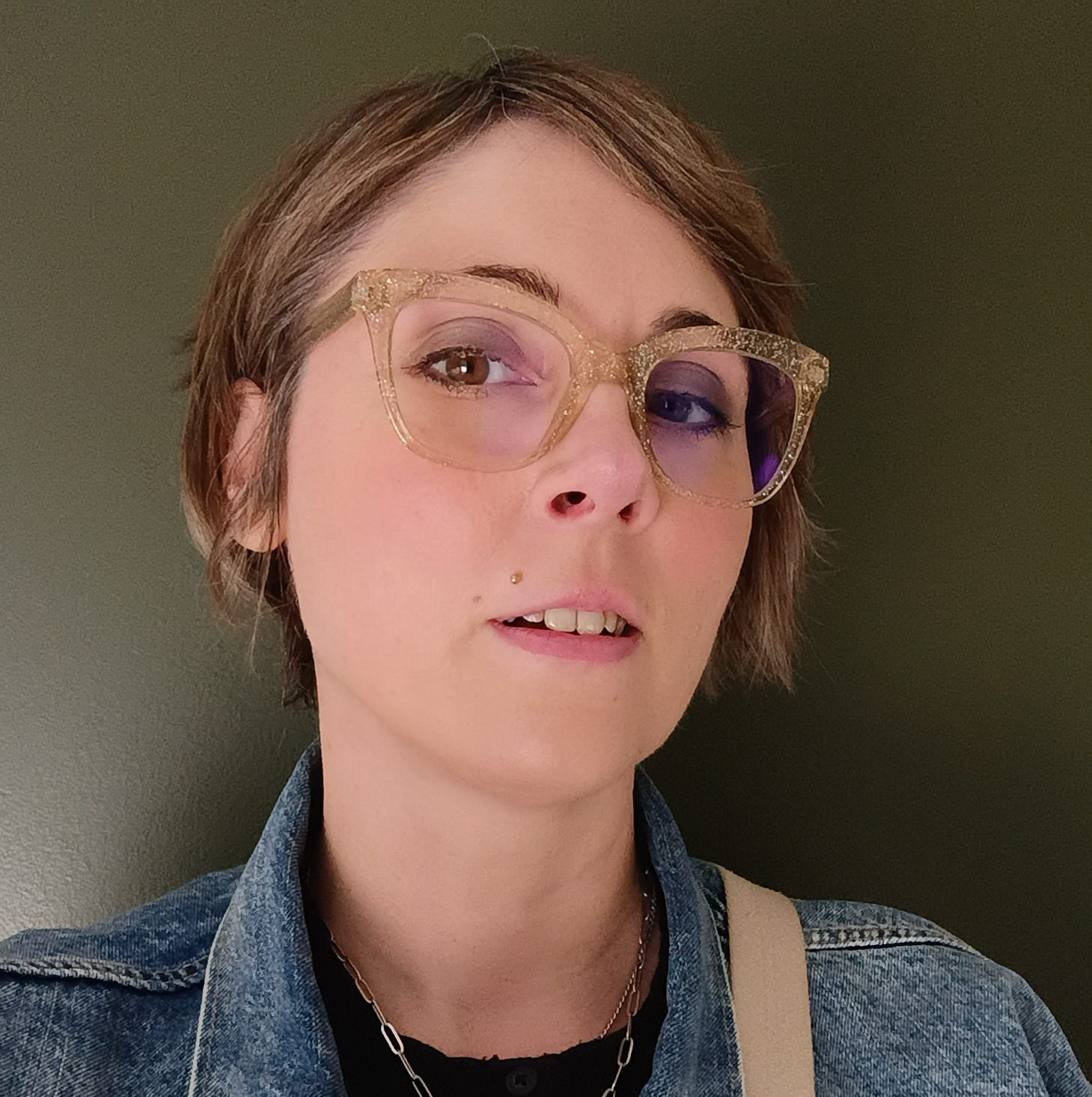

Sarah Sorensen (she/her) MA, MLIS is a queer writer based in the Metro Detroit area. She’s honored to be named a 2025 Best Small Fictions author and runner-up in the 2025 RockPaperPoem Poetry Contest. Sarah’s poetry chapbook, Light Splits Down the Wolf’s Tooth (Bottlecap Press) just dropped.

✶

Whenever possible, we link book titles to Bookshop, an independent bookselling site. As a Bookshop affiliate, Another Chicago Magazine earns a small percentage from qualifying purchases.