Prologue

I’m sitting in L’s room: Graphite pencils, carbon pencils, Cheez-Its left in round, BPA-free bowls, Cheerios because I beg him to eat something, anything, fortified with iron. His paintings of owls. Posters of the ocean. Whales with baleen and their own groaning songs. How L loves this world. On the bookshelf — anime merch, wooden katanas, relics from his previous life. In the center of the room, my child lies on a mattress on the floor so that he won’t faint getting out of bed. “If it’s on the floor, I can crawl to you,” he says. “Unless my legs stop working, in which case I’ll call for you.” His legs always stop working. Sometimes we get lucky and it’s only his legs. It’s been 1,228 days – nauseous, throbbing, foggy, orthostatic days.

In the Notebooks of Leonardo Da Vinci there is a sketch of a fetus inside the mother’s womb and an entry below: The soul apparently resides in the seat of the judgment, and the judgment apparently resides in the place where all the senses meet, which is called the common sense. I’m a big fan of common sense. It’s how I travelled solo across Nepal and Thailand. It’s how I climbed twice, to 13,770 feet to where elk looked like shaggy dolls under cumulonimbus. Logic drives me to pay attention to upslope fog and ice fog. But what is good is common sense divorced from empathy?

My boy has always been right about his body. When he was twenty months old and didn’t yet have the linguistic skills to say: mama, my lower belly hurts all the way to my groin, he pointed to his nether regions and said, “OWIE.” He was correct—inguinal hernia. Surgery a week later. Also, correct about incipient fractures in growth plates while playground teachers shook their heads: Walk it off. You’re fine. Then mono. Strep throat. And mono again. When he hurts, I listen. And when I can’t make it all better, I trust that doctors have deliberate and implicit acceptance of the patient’s testimony, until I don’t. Primum non nocere — First, do no harm, so said Hippocrates.

With This One Hour

It’s June 2025. My son’s been sick with Long Covid for over three years, which is nothing compared to other kids who’ve been suffering longer. Elite runners in wheelchairs. Dancers asleep with their heads bent like pointe shoes. The lacrosse star who cannot stand without fainting. And the pediatricians flagging them all: Child in no apparent distress. Labs, normal. EKG, normal. Diagnosis: anxiety. Diagnosis: conversion disorder. Diagnosis: depression. Millions of children worldwide with tachycardia, all passing out. Where is our common sense? Go back to school, they say. Be a normal kid and you’ll start feeling better soon. The sound of the disposable paper crinkling over the examination table as they rush us out to accommodate an easier case. The crinkly paper loud as my son’s silent: Fuck You, doctor. I know what I feel. Listen to my mom. I am in pain all the time. She sleeps on my floor every night. Please — go back to Human School.

I spend hours each day and night reading peer-reviewed journals while my husband carries him back and forth to the bathroom. Podcasts between appointments. I hear kids laughing down the street, but not at our house where we discuss new meds ad nauseam. Care teams. Up-and-coming specialists. L does forty sessions of hyperbaric oxygen. I take him to Mexico for stem cell infusions. We fly to Alaska for Stellate Ganglion Blocks. We’re grateful we can afford this; many can’t. We compare airport wheelchair transports as though they were a hot new streetwear clothing brand. After every trip, my boy contracts Covid for what seems like the thousandth time. Reactivated Ebstein-Barr. Strep. Our life has become one never-ending episode of the Twilight Zone. Or worse–Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

I’ve always hated the phrase, “Let’s play it by ear” because it feels so wishy-washy. An insipid, indecisive way of charting one’s way toward progress. But homeschooling a child with Long Covid is inherently irresolute. Like sending a homing pigeon with clipped wings into the scented winds with a message for the king. Sometimes my son will find a cool Youtube physics video which allows him an assemblance of an education. We do what we can with this one hour. Maybe the video leads to conversation about science. Maybe it leads to an art project. When he finds a pain-tolerant, vertical-tolerant window of time, L teaches himself how to cook dishes out of the freshest of ingredients – garlic scapes, local butter, organic beef. If he can stomach it, he wants something besides processed crackers. He stands at the kitchen counter as long as he can without passing out. By the three-year mark he had tried fifty-two different medications, but no magic bullet.

Between experimental treatments I talk endlessly to other moms, desperate also to save their children. Hours on the phone to Nebraska, Minnesota, Virginia. We-the-moms understand the urgency in each other’s voice. A perfectly symbiotic Hellscape we are grateful to share because there is no other landscape safe enough for open Long Covid dialogue. One mom details how her son was training to play D-1 soccer, but is now on a feeding tube, still vomiting ten-to-twenty times a day. Another mom was “lucky enough” to discover micro-clots throughout her son’s body, but her doctor didn’t know how to treat them given they were “micro” and not your average thrombus. We-the-moms exchange doctors’ contacts, clinic reviews, symptom checklists, before- and-after photos of our beloved kiddos.

By seventh grade students often work with percentages, fractions, probability and proportional relationships. Math looks different at our Long Covid house. We practice for survival, not standardized testing. What percentage of a medication is metabolized by the liver? By the kidneys? What fraction of the pediatric population gets well? What is the probability that a new doctor will listen and treat? What is the proportional relationship of spending fifteen minutes outside (Y) to the post-exertional malaise (that follows XP). This is a “joy tax.” Crashing for weeks (sometimes months) after a short walk. This is what we tell Child Protective Services when the public school reports us for habitual truancy and Munchausen by proxy.

1954

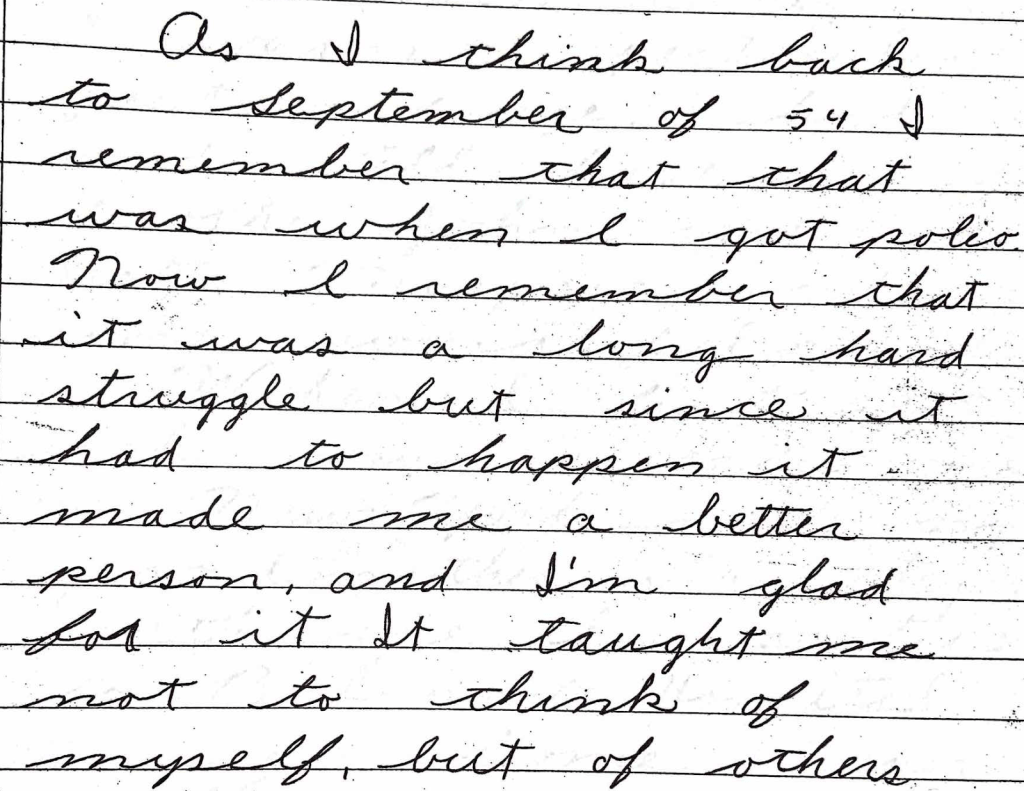

In September 1954 the daily temperature in Worcester, Massachusetts, averaged seventy to seventy-five degrees with little precipitation. There were so many places to swim before autumn: Patch Reservoir near Chandler Street with its chestnut and elm trees. Indian Lake with its unfortunate name and glassy veneer. Salisbury Street’s swimming pool-sized pond with more ducks than beach towels. I’m assuming it was one of these inglorious sink holes where my twelve-year old father, a newly minted seventh-grader, contracted polio. Seven months later, the radio would broadcast that Jonas Salk had invented the first polio vaccine.

Confucius wrote, Three things cannot long be hidden: the sun, the moon, and the truth. True, Salk provided the world a miraculous feat of science, saving countless people from the iron lung, putrid-smelling Kenny packs made of boiled wool to help relax the muscles. Though in truth it was the groundbreaking work of Albert Sabin, who discovered how enteroviruses invade the gut before making their pilgrimage to the nervous system. In pure architectonic form, this man who emigrated to the United States from Poland to escape antisemitic persecution developed the oral live-virus polio vaccine – a pathway for humans to avoid the persecution of a paralyzing pathogen.

It’s not hard to imagine my father at that age. Capri-blue eyes, dirty blond hair. Dragnet, Gunsmoke, The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet playing on the Arvin portable FM just before the transistor was introduced later that year. I knew from the way he collected canes as an adult—refusing to ever use one—my dad was too proud to ever be seen as handicapped. Truly, his deformity was only noticeable in shorts, his left leg like a stick compared to his normally developed right leg. The only way his calf muscle could contract was because of a sinewy transplant from his big toe.

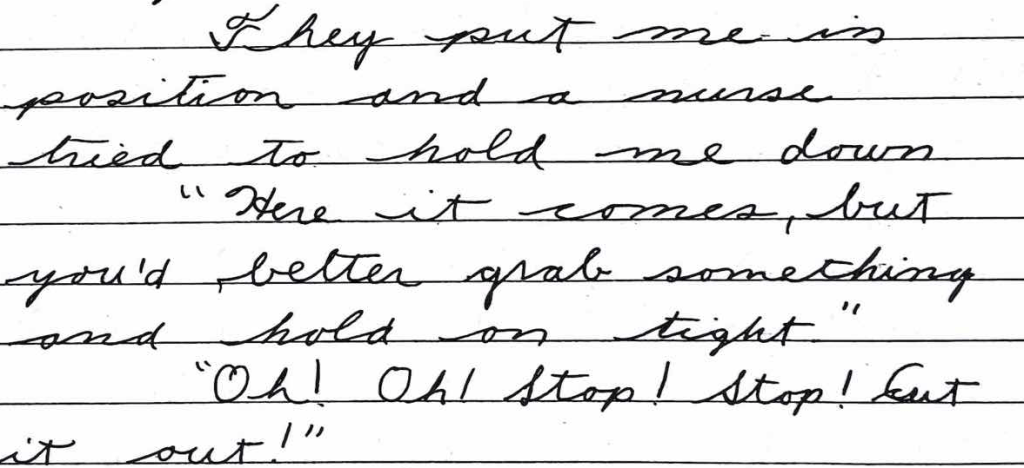

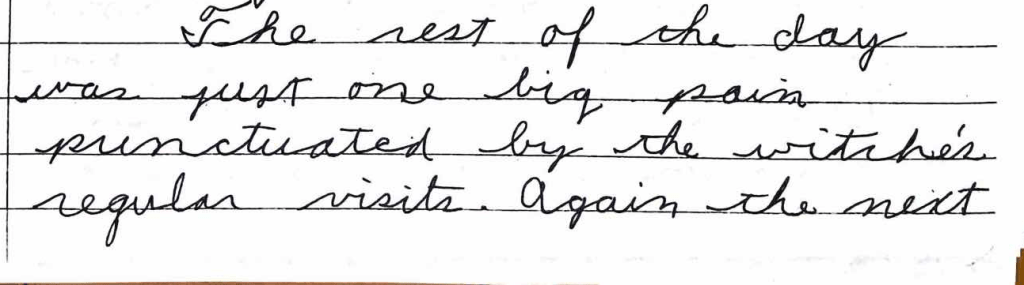

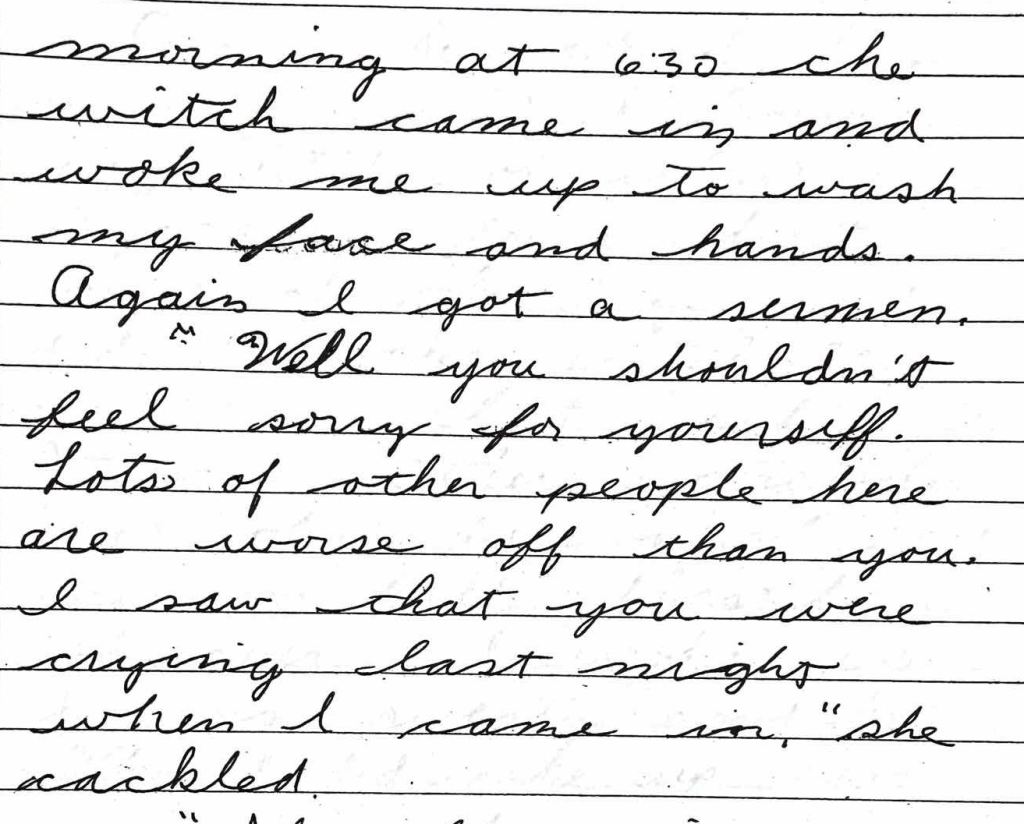

When my dad wrote his polio story two years later, at the age of fourteen, I must assume it was a school assignment. He was never one for creative writing, especially a personal narrative. One woman who has become clear to me is the ghost-character, the woman behind the scenes: the one in a slim pencil skirt, the one who sat behind glass to reassure him that he would never be alone, the one who was named Dorothy Burwick, or “Mama Doll” as she is always referred to in stories, is said to have been a slender, demure beauty in a sweetheart neckline, or a Christian Dior cardigan.

She was a political wife. A Jewish Jackie O. Her husband “Papa Charlie” was a prominent lawyer and staunch supporter of local and state Democrats. Any given hour of the night, her husband would bring fellow lawyers, judges and politicians home to gather around their living room table. So, the Worcester/Boston community was her Camelot, and she was poised to wear the “everything-is-OK” face at all hours. Did she allow her mascara to smear when overwhelmed with grief? Did she sit at the window of my father’s room in fashion-forward sweaters every day?

The only way to definitively know if this was polio was by doing a spinal tap–an incredibly painful lumbar puncture technique for drawing cerebrospinal fluid. No one prepared him for this procedure. Held down and terrified, my father described this as one of the most terrifying tests of his life.

Of all animals, the orangutan forms one of the strongest bonds between mother and its young. The African elephant and emperor penguin are also in the running. But if you’ve ever seen a video of a mother orangutan, you know she is fierce. She uses her own limbs as a living bridge to help her young cross gaps in the forest. She’ll nurse them until they are six. She’ll raise them for a decade. She’ll even collect nectar if it means soothing her young.

When Mama Doll heard about this woman who used her nursing position as an opportunity to practice authoritative parenting, she’d had enough. Nobody was going to reprimand her boy for shedding tears in muscle-paralyzing, solitary confinement. Not this Wicked W-witch of the East with her starched hemline. Not anyone. She wasn’t someone who had gone to Human School. In 1954, while September was limping towards October, Dolly convinced Charlie to find their son a private nurse since they were lucky enough to have the means to do so. They found a man who worked on a police ambulance and occasionally took private patients. To my dad, he seemed straight out of Dragnet, his favorite radio show. Now, instead of the witch, it was like having Joe Friday sitting beside his hospital bed . He filled my father’s days and nights with ambulance stories and, embellished or not, they made my dad laugh. October became November. Marilyn Monroe divorced Joe DiMaggio. West Germany joined NATO. Kids trick-or-treated. Hemingway won the Nobel. And my father, in tempest speed, was driven from Worcester to Boston Children’s Hospital.

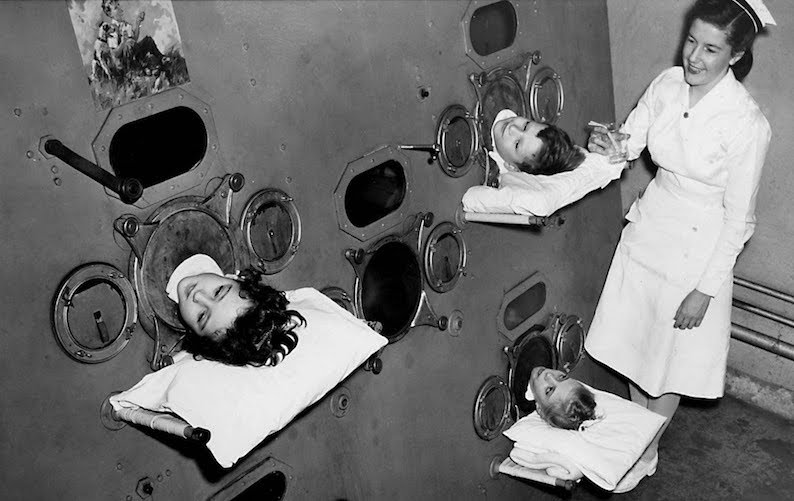

In Boston, my dad would certainly have more advanced care, but he would also see horrifying scenes of other sick children. When my dad arrived at Children’s Hospital he found diversity in polio’s wrath. Kids in iron lungs. Arms and legs wasting away. Twice a day nurses would come with their Satan-hot healing packs. Cocoons of boiled wool – putrid like rotting fish over rotting eggs. There was so much debate among top doctors. Did the pack help the twitching muscles recover? Or did muscle spasms lead to additional risks of paralysis?

In a photo from Boston Children’s Hospital Archives, kids are seen encased in iron lungs. In this cylindrical ventilator sixty to eighty percent of kids died. The ones who survived in the chambers could not eat or swallow on their own. All his life, my dad considered himself the luckiest man on earth because he saw these contraptions and was not confined to them.

In his adulthood, my dad began collecting clowns. Papier-mâché figures hanging from green parachutes. Vintage 1970’s primary colors clowns holding balloons. Sad eyes in golf carts. Clowns with an umbrella standing on one foot.

There were paragliders and sailors. Somber clowns with violins and creepier ones with accordions. He also bought smaller, marble clowns hidden which he hid in corners through the house. Exquisite and horrifying, 24K gold plated– a clown in a bathtub with a dog, a tightrope walker, a clown with an umbrella and giant shoes. Or, my personal favorite– the Ron Lee series: reclining fisherman clown with swordfish.

The “humor therapy movement” arose in the early 1930s because doctors began to theorize that laughter could promote healing on a cellular level. Boston Children’s Hospital was one of a few top hospitals who brought clowns into the polio ward. With their outrageously oversized shoes and their balloon noses and absurdly upside-down red triangle smiles my dad was smitten. These clowns were everything to him. They broke up the monotony of the days which felt like years. They gave him agency to giggle and to dream of a world beyond this epidemic.

When the holidays approached, doctors told my dad’s parents that he could return home in January. He could not walk. He would never walk again. The word never hangs over his hospital room. Soon, other words hung in the air: balance, atrophy, stability, braces, crutches, muscle transplants, canes.

Mrs. Hofschire’s House

We were Jews. This meant every Christmas Eve our family went to the local Chinese restaurant. Plates of spare ribs and sweet and sour chicken while the rest of my known world was awash in fur, pine and tinsel. Clinquant ribbons and white-frosted cookies that looked as if professional elves had crafted each and dipped them in silver glitter. Were fortune cookies supposed to take the place of this pageantry? “Not to worry,” my dad would say, “we always stop at Mrs. Hofschire’s house.”

Irja Rachel (Ryssy) Hofschire: As a kid, I knew only two things about this tiny woman: She taught my dad how to walk after polio had paralyzed him, and she had the best Christmas tree in town. Ceiling high with silver and sapphire lights. With thinning white hair and cataracts on both eyes she looked older than Yoda. Mrs. Hofschire had graduated from the University of Wisconsin Medical School for Physical Therapy in 1943 and after the war, continued as a civilian physical therapist for polio-afflicted children in Massachusetts. Clearly, the doctors at Boston Children’s had never been in the presence of Irja Hofschire.

The history of aquatic therapy dates back thousands of years. The Greeks used it. The Romans. The Egyptians. Swiss monks. The Japanese. Still, in 1954 it was Mrs. Hofschire, not Boston Children’s, who utilized this method of rehabilitation. It’s simple physics: the water serves as a resistance medium for patients to regain strength with buoyancy as opposed to land therapy, which puts more strain on joints. My dad practiced walking in the pool for hours a day. Legend has it, my dad brought two crutches to his bar mitzvah. He looked toward the bimah, angled the wooded sticks against a chair, and walked the length of the synagogue unassisted. Tiny, blessed sobs. I start thinking of my son again. What if he had contracted polio instead of Long Covid? What if poliomyelitis was undetectable in cerebral fluid? Would Mama Doll have been accused of Munchausen’s?

Epilogue

According to CBS News, by March 2024, 5.8 million kids had been suffering from Long Covid. By October 2024, there were only two registered drug trials for Long Covid in kids — one in the U.S. and one in Pakistan. By Halloween 2024 we were investigated by Child Protective Services for the third time. Report after report: Parents are trying unconventional treatments. Child with truancy. Parents state the child is too fatigued and has too much body pain to engage in normal activities.

According to the NIH and the Mayo Clinic, “In research studies, more than 200 symptoms have been linked to long COVID.” Our son had over 100 of these symptoms. Acute nausea, nerve pain, migraines, periodic paralysis, blurry vision, tinnitus, temperature dysregulation. I could go on and on. The one time the public school believed us was when L fell unconscious on the playground and when he woke, he couldn’t move or speak. A “normal” day for us, but panic set in quickly among the staff. I thought of my father who walked when the world said it wasn’t possible. I needed to get L better so he could do the equivalent.

My dad died of lung cancer during the first few days of 2019. He missed the Covid lockdown, cloth masks then N-95s. He thankfully didn’t have to relive watching his grandson suffer the way he did. During the last two decades of his life, he developed post-polio syndrome (PPS). Muscles weakness, pain, fatigue and more atrophy. He sought out the best post-polio syndrome clinics. Some doctors had him restart physical therapy. Some sent him to a website for cool, new braces. But like Covid, there was no direction and no cure.

Leonardo Da Vinci writes, “Iron rusts from disuse; water loses its purity from stagnation … even so does inaction sap the vigor of the mind.” I refused to stagnate. After hyperbaric oxygen chambers, stem cells, and off-label meds repurposed for immune function didn’t work, we did body work, magnet work, and red light therapy. Nothing moved the needle. At nine, he was reading at a college level. By age eleven there were days when our son couldn’t sound out his own name. He had to practice speaking the request: Food, please.

Our story may or may not have a happy ending. After six months CPS closed the most recent investigation as unfounded, though the memory of it created an awful background silence. We are ten months into another unconventional treatment which uses the patient’s own platelets to help heal the immune system. After the first treatment many of his Long Covid symptoms were deleted like a miraculous factory reset. His paralysis ended. His migraines lessened. But he still suffers mind-numbing fatigue and body pain. He asks: Is this what bone cancer feels like? He’s better, but not yet well enough to attend school in person. Recovery is not linear.

Will this nightmare end? Who’s to say? Living with the fear of not knowing wakes me from midnight sleep. The only constant we have is action. Inaction is not an option for a parent dedicated to getting their child healthy. Inaction is the death of the once-healthy body and soul.

✶✶✶✶

Kimberly Burwick was born and raised in Worcester, Massachusetts. She is the author of six collections of poetry, most recently Out Beyond the Land published by Carnegie Mellon University Press. She has taught at numerous colleges and universities including U-Conn, Washington State University, University of Iceland and others. She lives in New Hampshire with her husband and teenage son.

✶

Patty Paine is the author of Grief & Other Animals, The Sounding Machine, and three chapbooks. Her writing and visual work have appeared in Blackbird, The Denver Quarterly, Gulf Stream, Waxwing, Analog Forever, Lomography, The South Dakota Review, and other publications. She is the founding editor of Diode Poetry Journal and Diode Editions and is director of liberal arts & sciences at VCUarts Qatar.

✶

Whenever possible, we link book titles to Bookshop, an independent bookselling site. As a Bookshop affiliate, Another Chicago Magazine earns a small percentage from qualifying purchases.