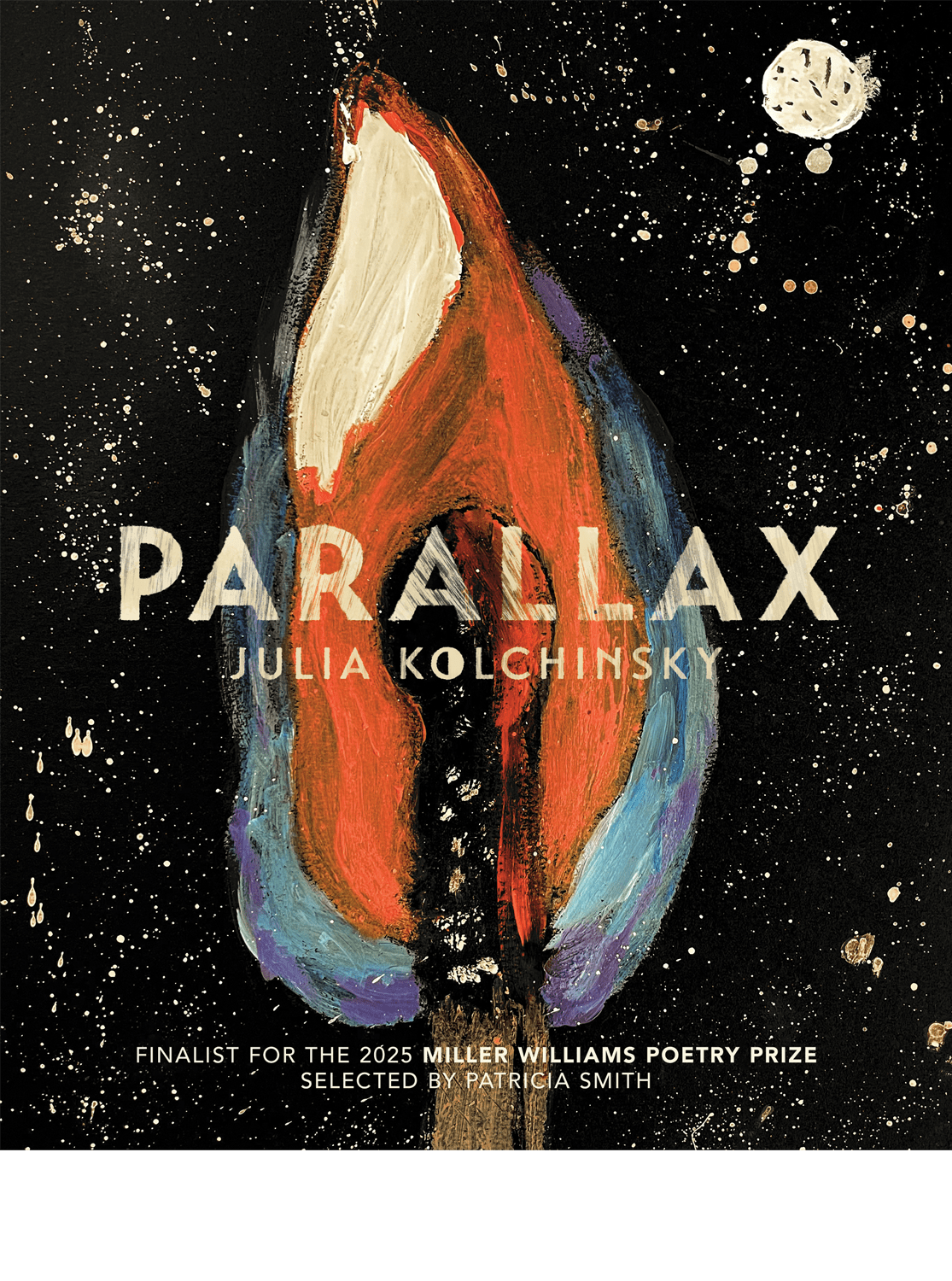

“Parallax,” University of Arkansas Press, 2025, 118 pp.

Julia Kolchinsky’s Parallax, selected by Patricia Smith as a finalist for the 2025 Miller Williams Poetry Prize, is a collection that interrogates one of the key questions at the heart of modern poetry: In a world ravaged by unending conflict and upheaval—military, domestic, especially in the poet’s native Ukraine—what relevance can poetry still claim? Can poetry still matter?

The sentiment is most explicitly and audaciously expressed in “Two Years Later,” in which the speaker admits, “The last thing I want is another poem.” Parallax does not shy away from its underlying questions; instead, it offers language as both witness and resistance to violence.

Formally, Parallax is structured in seven sections, bookended by “Initial Singularity,” a nod to the Big Bang and the universe’s violent conception, and “Afterglow,” which may refer to both the scattering of light particles and a kind of euphoric release. The sections in between are entitled “Carbon,” “Hydrogen,” “Phosphorus,” “Oxygen,” and “Nitrogen”; as the author notes, these elements form inside stars and are involved in biological processes, including the construction of human DNA.

Parallax opens with a tone of indifference toward violence, while the elemental sections create a sense of transience—what might be read as “what happens while the dust settles.” Quotations from Holocaust survivor and chemist Primo Levi serve as guideposts for these sections, providing emotional scaffolding and guiding the reader through the structure of each one. Importantly, Levi studied these chemical elements to grapple with the aftermath of war and loss.

Kolchinsky continues the emotional and thematic threads of her previous collection, 40 Weeks (YesYes Books, 2023), again navigating the unmappable terrain of motherhood and parenthood, though this time set against the grim and shifting landscape of war. The result is a collection that is both intimate and universally urgent, personal and unflinchingly blunt.

As the title suggests, this is a book about vantage and perception. In several poems, the speaker takes an empathetic approach, trying to see the world through the eyes of her neurodivergent son. Elsewhere, she poses the question: “How can I teach my child to live through and/or in violence, without becoming violent themselves?”

In Parallax, everything is war, even as the lens through which it is viewed varies. The opening poems establish this: Violence is met with a mix of detached curiosity and a desperate, parental urge to shield children from it. There are moments when war and parenthood exist on the same violent plane, and perspective matters; Kolchinsky handles this tension with care, never qualifying or equating it to the act of parenting. It is volatile but distinct, and her speaker is fractured, torn between parenting, grieving, and witnessing war poison her home country of Ukraine, as in “On the 100th day of war in my birthplace:”

The rhododendrons keep blooming

despite the blood.

Through some lens, the concept of home constructed through memory is blurred by time, loss, and fear. One of the most compelling aspects of this collection is the speaker’s fear for and of her child. The concept echoes throughout the entire book, and the reader is acutely aware of the responsibility involved in explaining violence. This dichotomy, the clear terror of the sentiment, is expressed in “Why write another poem about the moon [with all her names & animals]”:

& if he’s this bad now—

the broken glass & bruises & bites,

the time he pushed his sister down

a flight of stairs—what will the future hold

Kolchinsky’s “Why write another poem about the moon” series constructs a universal framework across the collection, each one appearing after moments of violence, allowing the moon to become a god-presence the speaker can rely on. Insomuch as the speaker’s children look to their mother for refuge and comfort, the mother-speaker turns to the moon.

In so many of the poems in Parallax, the speaker is aware of the impermanence of childhood but the immutability of parenthood. The line between parent and child is often blurred, most notably in moments when the speaker herself is wracked with frustration at parenthood, as in “After the third snow day in a row, I’m ready to throw the towel”:

at my children yes their screaming

at my children their faces needing

always needing more

pink paper & play more water more

food different from whatever I’ve made more

more mama closer than sound lets on mama

from every room echoes the house & where

is she where? this me named need

In our current climate, Parallax offers a glimpse into both the universal and the intimate. Kolchinsky’s poems are audacious in their interpretation of the horrors of war, and of motherhood and parenthood—the fear that children will not understand our mistakes well enough to learn from them, and that when they encounter wars of their own, they will not know how to bear that burden.

To fully appreciate the world Kolchinsky has constructed, one must acknowledge that truth depends on the angle from which it is viewed. Kolchinsky’s Parallax does not offer easy answers to the questions posed early in the collection—whether poetry still matters in a world undone by war and grief—but she insists on asking again and again, from different angles, in different lights. What emerges is not an answer to this question but a shifting truth: Poetry becomes a means of survival, a vessel for witness, and a fragile hope for empathy. By looking slant, by shifting the lens from mother to child, from Ukraine to the moon, Kolchinsky proves that poetry’s relevance lies not in resolution but in its willingness to hold contradiction—to name the violence and still sing.

✶✶✶✶

Jill Mceldowney is the author of Otherlight (YesYes Books, 2023), ALYDAR, forthcoming from YesYes Books, and is finalist for the Julie Suk Prize and winner of a North American Book Award. She is a recent National Poetry Series finalist and a founder and editor of Madhouse Press. Her previously published work can be found in journals such as Tupelo Quarterly, Prairie Schooner, Fugue, The Journal, and Muzzle.

✶

Whenever possible, we link book titles to Bookshop, an independent bookselling site. As a Bookshop affiliate, Another Chicago Magazine earns a small percentage from qualifying purchases.