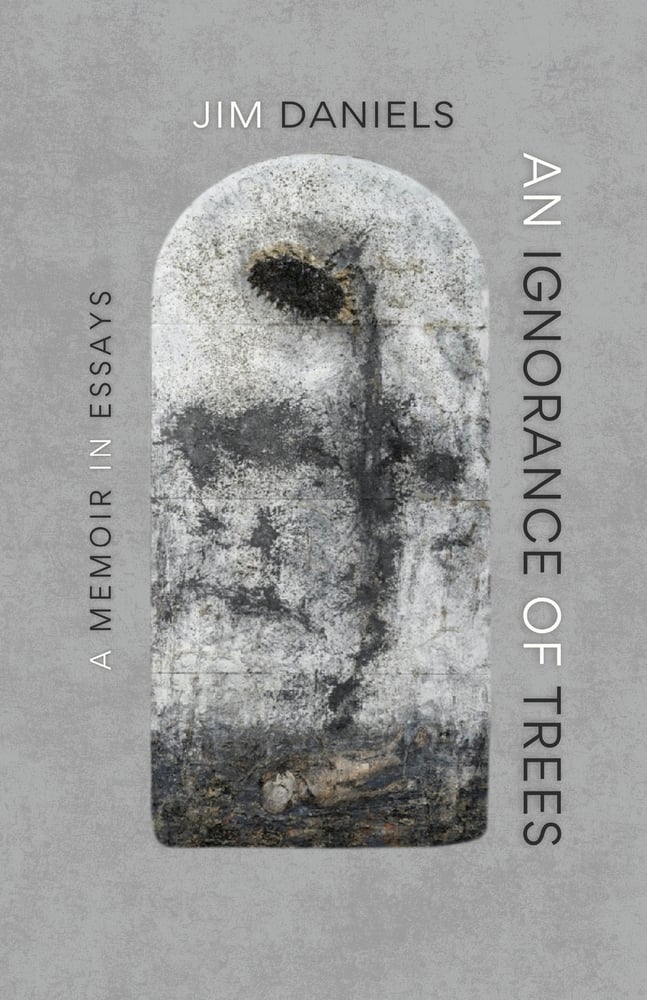

An Ignorance of Trees, A Memoir in Essays by Jim Daniels, 2025, pp 180.

If you carry a secret to the grave, you are holding on to that secret throughout your entire life. You are only done keeping the secret when you are dead in your grave.

My mother died on February 29, 2020. Leap Day. While approaching the next February 29, my father was still waiting for his income tax refund from the previous year. He had written DECEASED next to my mother’s name on his return. That threw the whole system off, sending his return into the void for further review. Since the entire IRS was working from home due to Covid-19, which arrived approximately two weeks after my mother’s death, apparently every day was now Leap Day, and perhaps in another four years my father might get his refund.

*

My mother’s ashes were, and still are, in a box on the floor in her bedroom closet awaiting my father’s death so they can go in the mausoleum together and save money—it costs every time you open the thing up. This tells you something about my father. He’ll be carrying a lot of things to the grave, but his frugality is well-known, so, despite him carrying it to his grave, it is not a secret.

He threatened to send some of her ashes to the IRS to prove she’s dead. My father failed to master their automated phone system, which is designed so that you will never be able to speak to an actual human being. That system works perfectly.

He said he may as well be talking to my mother’s ashes. He might already be talking to them. I don’t know what he does late at night, alone in their condo, when he can’t sleep. Though I can’t picture him digging in to scoop some into an envelope. He always curses at tax time, “What do they want, a pound of flesh?” He sharpens his pencils as if planning to stab someone.

*

In 2022, he got his 2021 refund check, but the 2020 one was still floating around in cyberspace, far, far from my parents’ condo in Sterling Heights, eight miles down the road from the house I grew up in next to Detroit. “Maybe the check’s on the floor in somebody’s basement,” my father said, and perhaps he was right. He’s never been to cyberspace and has no intention of going, though when he was 93, he did invest in his first bicycle helmet, so maybe he’ll surprise us. When my well-meaning brother gave him a GPS for Christmas back when it was something you bought separately for your car, he made my brother return it. He knows where he’s going.

This is the brother I call “The New Duke.” “The Old Duke” is my father, a moniker given by my grandfather, who my father treated just like my brother is treating him as he’s aged—with impatience and condescension.

*

My father’s been telling me if there’s anything in the condo that I want when he dies, to let him know, though he’s not putting masking-taped names on the bottom of everything like my mother did. He has always been averse to clutter. My grandfather, on the other hand, had stopped caring. It seemed like he wanted to pile more and more junk on top of his heart so that no one could find it. “The first Duke used to go over to Grandpa’s house and do a purge, then take the trash out to the curb. My grandfather would take everything back in after my father left.

*

My father filed a paper return, so he was really in for it—his return was probably in some dinosaur cave being used to start a fire. With his sharp pencils and accountant’s clear numbers, my father still pays his own bills at 95 and still does his own taxes. Despite “The New Duke” trying to step in and take over. Or, perhaps because he is. The dining room table’s covered in piles of paper—very neat piles—for at least a month every year now. Hey, it’s not like he’s throwing any dinner parties.

My brothers and I picked up “The Duke” thing from Grandpa and started calling our father that behind his back. When “The New Duke” bought him a sports shirt for Christmas with “The Duke” stitched on the front like it was an alligator or some other designer brand, our father gave his famous pained, constipated expression and refused to try it on, even for a quick photo. He was not owning “The Duke,” the nickname for John Wayne, the actor famous for his macho swagger in Westerns and war movies. A classic tough guy, his real name was Marion, and that just wouldn’t do for a cowboy/war hero.

*

In old age, my father’s new nickname has become “The Microwave King.” He fills the freezer with frozen meals from Kroger’s (one of the three places he still drives to, the others being church on Sunday and my sister’s house, all within a radius of three miles), lining the boxes up like library books, using his private Duke decimal system. He picks out his daily selection from the frosty rows and zaps it at dinnertime, quite content to eat one every night. Sometimes he’s in a Hungry Man mood; sometimes, it’s more of a Stouffer’s day.

The microwave still has the raised buttons my father created for my blind mother in order to turn it into an ersatz braille zapper. He stuck on little round furniture protectors, and they mostly worked fine. My father misses my mother, even those crazy surprises, like finding she’d placed a carton of ice cream in the dishwasher instead of the freezer.

The stove burners still have the squiggly red lines he painted on them when she still had some vision. He doesn’t use the stove at all now, not that he ever used it before, except for special occasions when he’d trot out his recipe for grilled cheese: bread, butter, cheese. He still uses the coffee maker, the toaster, and the microwave—the trinity of the rest of his life.

*

I call him on the phone from Pittsburgh once a week, so I’m guessing he told me at least fifty times that he was still waiting for his tax return. I’ll come back to that, like he came back to it—something to lean on, a clear injustice he could point to after a lifetime of unspoken or whispered injustices.

He said he wrote DECEASED in all capital letters on the return, so there should be no doubt about the fact of her death. I’m sure he did. He’s always believed in capital letters. Though, actually, he didn’t believe much in writing—the longest letter I ever got for him was one short paragraph, accompanied by a check. He seemed quite content to let the money do the talking. My mother wrote me weekly letters for years, and sometimes I feel like I’m paying her back with the weekly call to my father. Those letters have survived many of my own family’s moves in my designated Memory Tub.

The Memory Tubs remind me of the empty beer cases we used as “suitcases” for our annual camping trip around Michigan—never a problem finding empty beer cases in our house. My mother painted them all some strange shade of purple with our initial on the side in white. They lined up like the six bag lunches my mother made every morning during the school year, also initialed. My dad put a board on top of the boxes, and it became my sister’s bed in the cramped crank-up camper. My father still has a couple of those in his basement, paint chipped and worn, that he uses for storage. The rest of the world has shifted to plastic tubs, but “The Duke” is just fine with the beer cases.

*

He did sometimes leave me notes on the kitchen table that I’d find in the morning after he’d already left for his job at the Ford factory: CLEAN UP YARD. This meant shovel up my dog Prince’s shit—I tended to let the piles accumulate, and Prince was a big dog. It was a dog’s bone of contention between us that someone kept digging up. To be honest, I think I liked the special attention of those notes—none of my four siblings ever got them.

Oddly enough, I never heard my father say “shit,” and certainly not “fuck.” He heard it all the time at work—I know, having worked at that same factory myself, where swearing was a casual kind of punctuation. Not a pious man—that’d be like bragging, which he never did—but he goes to church every Sunday. He dutifully pushed my mother in her wheelchair into the handicapped row in the back every Sunday until one day she spat out the host—out of sorts, and out of her mind. Embarrassed, he never took her back. My mother, who prayed a rosary every night (she needed no help fingering the beads in the dark), could spit out “shit” in anger or frustration with the best of them. The rest of us—we took after her in that department. My father was working too much overtime to notice.

My mother would have called the IRS on some heavenly direct line and said “What is this shit, holding back the check because I’m dead?” My sister said she actually got a person on the line twice in her months of calling for him, but that the two gentlemen gave her completely opposite answers. Shit!

Well, at least they can’t drive dad to an early grave, I told my sister. That ship has sailed, I told her. I like mixing metaphors. My father, on the other hand, does not believe in them. He seems upset that It is what it is has become such a cliché these days and claims to have invented the phrase years ago.

*

His tax return had been flagged—it has been tarred and feathered, it made a wrong turn in Hell Freezes Over, Nebraska—apparently because he wrote something human on the form after losing his wife of 69 years, not sticking with numbers for a computer to scan. Maybe they thought he was being sarcastic with the caps. I really can’t say. He wanted to find an office he could drive to so he can complain in person. Go over the paperwork spread out on a table. Point to things with his sharp pencil.

No direct deposit for him, so on top of everything, he was waiting for a PAPER CHECK (caps mine). He uses his credit card as often as he used to use his camera: Not Very. The credit card has always been something suspicious to him. He wants to hand over the dirty, wrinkled dollar bills of his many years of hard work, not some cheap piece of plastic.

*

During the height of Covid, my father dutifully wore a mask, but pulled it down whenever he wanted to speak. Or hear someone else speak. Somehow, it made sense to him. If he was paying for something—like the weekly after-church donuts—we’d stand behind him and make apologetic eye contact with whoever was working the cash register as he bent down, leaned in, and pulled his mask down to hear how much he owed.

Though I have to give him credit (with a reduced grade for lateness), he now has hearing aids. First one, then a second one! He advises anyone to get two now, suddenly the expert after years of resistance. Of course, they’re always too loud for him—too late for the mind-ear connection to even things out. He’s probably secretly turned them off, or down so low that the devices are only a prop to keep us from bugging him about his hearing. We got him the fancy Bluetooth kind so he can talk on the phone through his hearing aids, though twice he has tried to hand me the phone—to speak to a relative or his one living friend who now is trapped in an Arizona nursing home—before remembering you can only hear through the hearing aids. Once, he took one out and handed it over to me like a tooth he’d just pulled and wanted a dime for. “Just talk into it,” he said.

Old habits die slowly, and no slower than his. He was never a phone guy, and when my mother was alive and we’d call, he’d answer, say hello, and quickly hand the phone to her.

*

He could make a roll of film last an entire year. Always a big surprise to see what was on it once he finally took it to the drug store to get developed. Some rolls had two Christmases on them. My father’s reluctance to finish a roll of film was legendary—he’d get the camera out of the closet like it was a bottle with a genie inside and he only had as many wishes as were on the roll. Often, only at the insistence of our mother, who wanted at least the obligatory holiday shots—all of us in one place, standing still, which was a rare occurrence. Maybe part of it goes back to the boogieman of our childhood: the absence of our father due to nonstop overtime at the plant back when the car companies couldn’t crank them out fast enough.

To actually finish a roll, knowing the inevitable dis/appointment/may/approval, etc., of the results, created anxiety for him, and he was a man rarely anxious—in the eyes of his children, anyway. He let the film stay there, spooled, safe in the dark, even once a roll was spent. Nothing could turn that tiny wound-up cocoon into a butterfly, given the ritual mugging of five goofy kids that it contained. Metamorphosis had too many syllables anyway, and sounded a lot like what had killed my grandmother.

If he didn’t develop the pictures, it’d keep us alive, safe—this, I realize now, was part of the odd, twisted logic of a man who had lost first his sister, then his brother, before graduating from high school. I didn’t find out they had even existed until I was away at college. Our childhood was full of odd silences that I only understand now. Nearly everyone else I knew, adult or child, had siblings—particularly in our Catholic neighborhood.

My sophomore year of college, I went to hear Neal Shine, an editor for The Detroit Free Press, give a talk. I knew he’d grown up in my father’s neighborhood on Detroit’s East Side, so I approached him afterwards and introduced myself. He smiled and said, “Sure, I knew your Dad, but I knew your Uncle Jack better.”

Uncle Jack? That explained a lot, if not everything. Sure, stories about cold, distant fathers are not unusual—a lot of Dukes out there. But I guess I’m not going with the cold, the distant. I’m going with another word that’s very familiar in these times, a word the Duke would never use: trauma. My father was two years older than his brother, who died of a burst appendix at age fifteen. His sister, Katherine, was a Down Syndrome child, though apparently this was hidden from my grandmother—perhaps by my grandfather—much longer than it should have been, until it became painfully obvious, and she was put in an institution, where she died at age fourteen.

His parents never recovered from those losses. Maybe they withheld their love from my father as a reaction to losing their other children. I do know this information, even now, is painfully sketchy. We’ve tried to bring it up with “The Duke,” but he pleads old age and fading memory. But withhold, they did. From him, and from each other.

Stories soaked in oil, drowned. That dark odor of family silence that we took as normal. My grandfather, a mechanic at Packard Motor Car Company, engraved his initials in every tool he owned, and on all his many toolboxes. They were his jewels, his treasure chests, our inheritance—and the silence of the accumulated unspoken, beyond the years in which he could fix anything, though all the tools in the world couldn’t fix what broke him.

*

Here’s a story about my father that doesn’t make sense until you know about those losses. His nephews Matt and Jon both played football in high school. Matt, the older one, had graduated, but he came back to see his brother play in the state playoffs. Here, I’ll let my father, who was at the game, take over:

“After the game, Matt went down from the stands and onto the field to comfort his brother.” Here, my father’s voice suddenly chokes up, and he has to pause. Then the pause lasts, and he says no more. The man who never chokes up, chokes up. A brother-memory flash causing him to shield his eyes.

*

My grandparents came over for most holidays. As kids, we sometimes spent weekends with them in Detroit. My grandmother took us to the dime store. My grandfather let us hammer nails into wood in his basement and pretend we were making boats. This all sounds like normal grandma and grandpa stuff. But it ignores the one cold room upstairs with a bunk bed in it that we were never supposed to enter, and the strange fact that my grandparents never went to church together, despite its being right across the street from their house.

My father never hugged or kissed his father or mother. He let them in the house. He took their coats, if they were wearing coats. They never exchanged gifts. If affection existed, it was sealed tight in a box, and none of us could open that package without ruining it, leaving evidence of our attempt.

My brothers and sister and I had to learn to hug and say “I love you” on our own. I can’t say when we started to express those emotions. After we all left home, I’m sure of that—we created an intimacy that could not exist in that house, with his firm handshakes and disdain for any—absolutely any—public affection. It was a learned behavior to break the handshake rule—expressions of love as a form of rebellion. I don’t even remember my father ever shaking his own father’s hand. Maybe it was a concession from him even to shake our hands goodnight.

*

Now that our mother is gone and he has no one to talk to all day, he’s suddenly become quite chatty. Well, he wouldn’t like the word “chatty”—the connotations wouldn’t suit the Duke. All I can say is that I’ve had conversations lasting at least a half hour. A HALF HOUR talking to him, even if it was spent going over the tax story one more time.

*

My father and his brother Jack went to Camp Ozanam together, a free summer camp on Lake Huron for city kids from low-income families in Detroit. My sister, scouring my father’s old papers, came across a letter and a postcard that they’d sent home from camp to their mother. To see my uncle’s childhood printing on the back of a postcard, even scanned by my sister and emailed, choked all five of us up. It made him real, and the loss for all of us—my grandparents, my father, and us, Jack’s niece and nephews—palpable.

July, 1942:

My father: “I gave Jack a postcard to write to you.” The older brother taking care of the younger.

My uncle: “I am haveing a swell time. I hope everything is the same.

Your loving son, Jack”

I can’t explain how just writing “Jack” puts a buzz and tremble in my fingers.

*

We drove the hour up from Detroit to celebrate my father’s 93rd birthday at an A&W drive-in out in the sun in Lexington, under an umbrella next to the parking lot. Lake Huron nearby, but we couldn’t see it from beside the main street of that small town. My father doesn’t own the cottage anymore, but he likes to take a drive up to go past it. He’s a happy passenger now, since the distance is beyond his driving limits.

We did not sing or eat cake—not singing, our gift to the world, and to ourselves, an entire family of self-conscious obeyers, fearful of both unwarranted attention and not being able to carry a tune. The parking lot was full, and so were the tables. He had to cup his hands to hear. Maybe it was enough for him to have two of his kids—my oldest brother and I—at that round sticky table. He wore a ball cap—did I tell you he played softball in a seniors’ league until he was 85? He sat up straight while eating his burger. I got a root beer float. Everything was for old time’s sake, and that was perfectly okay. Our family was never right on the water. It was enough to know the lake was out there, unchanging.

Oh, sure, water levels increased, decreased, the stretch of beach expanded and contracted from year to year. On the other side, it was still Canada. We always liked Canada, crossing the Ambassador Bridge in the station wagon on some camping trip. Didn’t we, Dad?

*

We’d driven past the “World’s Largest Yard Sale” to get into Lexington. It stretched on and on for miles down the two-lane highway. Cars parked on the shoulders, as if stopping haphazard at the scene of an accident.

We did not stop. “The Duke” has no need for any junk, extravagant or simple. His lifetime project of clearing out his own junk was in full-swing. Or half-swing. It keeps him occupied: “See anything you want to have, you know, when I’m gone?” Everything takes a long time now. Our sister is trying to save whatever evidence she can find of Katherine and Jack.

We all miss my mother. My brother’s wife did not come up to Lexington. My father and I are secretly relieved. We don’t have to make small talk or large talk. He is currently a connoisseur of silence. If we listen closely enough, he will explain it to us, once he stops slurping his root beer.

*

The first picture we ever saw of my father and Jack, they were both dressed up, hair slicked back, for some high school occasion worthy of a photograph. They stood together on the street across from St. Rose, their church that sat directly across their house on the East Side of Detroit. Despite that, my uncle was always late for school, Neal Shine told me.

For years, that one photo was the only evidence—until both my great aunt and my grandfather died, and new photos` emerged. I have studied and studied that picture, scanned into the family folder on my laptop. A couple of cocky, good-looking boys who were in it together, whatever it was.

*

Last time I was home to visit, I fell back on the ritual, which he’s always insisted on, to shake hands with him to say goodnight before heading to bed—at “bedtime,” back when we were kids, on nights when he was home from work. He would insist that we squeeze harder, and insisted that my own son squeeze harder when he was visiting with me while I stood silently cringing.

Were those handshakes his idea of love? I’m moving to the present now, wanting to feel his hand in mine, gripping hard (though not as hard as back when).

I’m tired from the long drive from Pittsburgh. It’s time for me to sleep. I’m 67, and he’s 95. His current routine is to fall asleep in his chair with the TV on. Should I wake him to say goodnight? No, not tonight.

I head up to bed in the Penthouse, the upstairs bedroom in the condo my parents moved into fifteen years ago, leaving the three-bedroom box that we were raised in, just in the nick of time. My mother’s sight was failing, but she was able to memorize the condo layout, blessed with the lack of stairs to climb. We occasionally had to redirect her when she ran into walls with her walker: “Left, Mom. Now, to the right”—but she managed for many years until she could manage no more.

My father, after having had cataract surgery, sees pretty well; he’s getting a little shaky at 95, and he sees that pretty clearly. He knows there will be no more film to develop. My mother put photos into albums and wrote corny captions. He never did corny. I think we all wish he did—at least once in a while—even him.

I wish I could shout directions at him, but this is an unfamiliar road he’ll have to navigate on his own, with no GPS. His faith in ritual and road maps remains unshaken, even as the lines fade. “I hope everything is the same.” Oh, to be that innocent child.

*

He’s closed the vents in my mother’s room, so her ashes are cold. He wants no speeches at his funeral. No jokes! No peppy music! It’s a funeral. It’s not supposed to be fun! He wants it: “Just plain.” No change-ups or modern stuff—just old-fashioned traditional silent grieving.

Please don’t be hard on the old guy now—just bow your head and pray.

*

Excuse me for getting choppy here near the end. The Duke would be disappointed. Stick to the script, he’d say. The present slips into the past as I back down his driveway…

*

One time, he didn’t stick to the script. Or maybe he planned it, though he had nothing written down. Here’s the story we tell each other, to affirm that this really happened. Some days he’s still “The Duke,” and, frustrated, he gets angry, and stubborn, trying to provoke a showdown on Main Street about moving his chin-up bar from the top of the basement stairs—he likes to stretch out there, he says, believing it keeps him from slouching over like the old man he is. On those days, we need this story:

At their 50th wedding anniversary party, after we had all had our say, my father took the microphone and said:

One time, my grandson Patrick came up to me and said, “I love you, Grandpa.” And I said, “That’s nice, Patrick.”

He said, “Grandpa, you’re supposed to say ‘I love you’ back.”

Well, I should have said it then, and I’ll say it now, “I love you all.”

The Duke. The one and only true Duke, now and forever.

*

I apologize to him for sometimes referring to him in the past tense. Every time I come home for a visit, when I’m ready to drive away, he makes the universal sign for roll down your window so he can tell me one more thing. Like, check your tires. That’s his favorite. They look a little low.

*

At 95, he sits alone in his open garage on the wooden tete-a-tete that he used to sit on with my mother back on the front porch of our old house. The empty seat creates an imbalance, as if it’s tilted by his weight. He started to re-stain it last year, but, tired of sanding, set that project aside. It looks a little rough, and it’ll stay that way. Plenty of room in the garage beside the one car, the last one he’ll buy from Ford’s with his employee discount.

He faces the sidewalk next to the loop road that circles his condo complex so he can catch the neighbors passing by to say hello. Mr. Microwave, happy for the human connection.

If someone wants to stop and chat, he’ll be happy to tell them about the tax return.

*

His favorite thing is the large-scale calendar we give him every year. We started getting it for our mother as she lost her sight, but now that she’s gone, he still likes filling in the large squares with his medical appointments in capital letters. When I tell him I’m coming to town, he writes down the date I’m arriving and leaving, and when I’m coming back again.

His brother, despite “haveing a swell time, never came back.

*

The check from the IRS, on the other hand, did, remarkably, show up, a year and a half later.

That same day he drove to the bank to deposit it. FOR DEPOSIT ONLY.

✶✶✶✶

Jim Daniels’s first book of nonfiction, An Ignorance of Trees, was published in August 2025. His latest fiction book, The Luck of the Fall, was published by Michigan State University Press. Recent poetry collections include The Human Engine at Dawn, Wolfson Press, Gun/Shy, Wayne State University Press, Comment Card, and Carnegie Mellon University Press. A native of Detroit, he currently lives in Pittsburgh and teaches in the Alma College low-residency MFA program.

✶

Whenever possible, we link book titles to Bookshop, an independent bookselling site. As a Bookshop affiliate, Another Chicago Magazine earns a small percentage from qualifying purchases.