This week, ACM is posting poetry every weekday.

Queen Shit

Friend of seventeen years, I can’t recall the bands

I listened to when I met you. Months ago

I quit folk songs, jangly banjo

now dull to me as a microwave’s hum, and when

I admitted this to you—under a dogwood in Atlanta

at a recent music festival—you squinted hard.

Was the sun in your eyes? I can’t recall, before

we had kids, if we smirked imagining their mouthiness.

We smoked a lot of Marlboros back then

never to share your dad was mean, my mom lenient,

never to consider our future parenting styles could differ.

At the festival, two beers in, I vented

my toddler plugs her nose in a parking lot-baked car,

cries that it stinks; you said sensory processing disorder

but I haven’t called my pediatrician. A worn guitar string—

is that our friendship? Still playing but faintly.

All I know is, the last night of the festival, I got stoned

and the midnight Uber ride to our hotel

lasted a lifetime. From the dark backseat I stared

at you in the passenger seat:

head cocked out the open window,

sunglasses big as cake pans

sliding down your nose,

arm stretched and index finger lifted

lazily pointing at a blur of cars, yelling I need pizza!

I remembered that same easy confidence

the day we met, the thunder

of your stilettos on the tiled hallway before you

entered that conference room, shoulders thrown back.

You’re a power ballad I’ll never tire of hearing.

Open Heart

We met in junior high on a track, looping the burnt-orange circle

not bothering to look up. No one counted steps or laps—

just walked until P.E. period ended.

Did I know we’d be lifelong friends? You chirped Hi louder than wrens

in pine trees edging the track. You listened, nodded,

as if I weren’t as average as a fallen pinecone,

as if time weren’t a race but barely budging, like hovering clouds.

In your 42nd year, we began a countdown to your surgery—

thirteen days until a doctor cracked your sternum.

Make that eighteen when the doctor came down with COVID.

Time was math: four glasses of Merlot to calm your hands

the day before you went under, three hours

the next morning until I received a text: you were awake, valves replaced.

I wanted to feed you cheese crisps from a crinkly bag

like we shared as college roommates,

to swirl ointment onto your scab—dark as dried figs, long as a baton—

but by the weekend I flew into your city and hugged you

gently, you said you’d fully recovered.

It will eventually be silver, you sighed wistfully, fingering

your pink scar peeking from your paisley blouse,

then we tramped

in staccato rain to a soggy farmers’ market and a man selling corn

told me Come back when it’s sunny, it’s even nicer

and time was a distant promise—

wait, things improve, around every corner is a prize.

Let’s go back to that track and crush pine needles

with our heels. Crush our watches too.

My Eight-year-old Can’t Find His Baby Blanket

I heard a poet say tattered is overused,

just as poems about motherhood are called trite, age-old, tattered.

Nevertheless, my son shakes me awake, my dream in tatters,

sobbing My blankie’s missing.

Muslin, washed-out red, and tattered from stretches,

nibbles, and that day as a toddler he tattered a corner with scissors,

his time-tattered blanket is in a box. I put it there.

No, I soothe, slide on tattered slippers, and guide him by his wide shoulders

back to his room.

Gauze-thin tatters dangle

from a keepsake box in his closet. I tug on the tatters

and the blanket tumbles onto his sleep-tattered hair. He crumples it,

curls himself around it, and cries. His window blinds tatter the sunrise.

I never want to lose it, he croaks, voice tattered.

I say it’s barely holding together,

almost rags, too tattered for nightly use. I don’t say

his childhood is fading, tattering, too. Lately his face looks like

nearly-baked bread, puffy and pale, the opposite of tattered;

as a teenager, will he want this tattered wad?

Tattered comic books on his nightstand give me an idea.

In the nightstand drawer we tuck his blanket, draping a tattered corner

over his favorite book. The blanket is safe from further tattering

yet easy to reach for

occasionally, in the dark, no one judging if he overuses tatters.

How to Play Basketball with Your Son

A golden shovel after Naomi Shihab Nye’s “Little Boys Running on the Dock”

Leap and release the ball, elbow slightly bent like a seagull’s

wing. If the ball skims the rim and slides in, don’t startle:

shrug as if your talent came easily. High-dribble and soar

up the court he’s chalked onto your driveway ten, fifty, a

hundred times. When you gave him this hoop, he curled onto its massive

plastic base and pretended to nap; now he’s taller, flapping

baguette-length arms in your eyes. Clutch the ball and

remember your first hoop: blended into backyard, mounted over-the-

rail of your parents’ two-story deck, draped with a hose. No boys

your son’s age spied it, no courage could compel you to call

their names. Pause beneath the net, mind wandering out-

of-bounds: how do you thank your child for friendship? Say Sorry—

I lost focus for a sec. Wave over the kids observing like hungry pigeons.

Figment

I swear my grandmother

used to cut a cold slab

of sharp cheddar cheese,

plop it onto a dessert plate

and microwave it

for ten seconds, just until

its waxy surface turned shiny,

its hard right angles rounded

and it plumped, wanting to melt.

She lifted it, nibbled.

When I share this memory, my knees

knock her walker,

a metal intruder as we sit

holding hands on her loveseat.

She can’t remember preparing

such a snack, although

it sounds tasty,

she says. I have no proof

so the memory

washes away like the greasy

orange imprint

left from the cheese, rinsed

off the plate.

At ninety-two

she is slowing down of course

but I can’t tell how much.

Hairdressers dye her feathered bob

the same copper shade

she had when I was a girl,

her hair color at birth,

like a flame never burning out.

Similarly eternal

is her love of chocolate; behind

my back are truffles I bought

on my drive here.

She plucks a dark raspberry

from the box

and dives in, moans,

closes her eyes. Her hand

squeezes the loveseat’s armrest

and momentarily trembles.

It’s the same response

she had to that cheese. I’m sure of it—she taught me,

a child, pleasure.

Just as her

forgetfulness teaches goodbye.

.

✶✶✶✶

Marianne Kunkel is the author of Hillary, Made Up (Stephen F. Austin State University Press) and The Laughing Game (Finishing Line Press), two anthologies, and poems that have appeared in Best American Poetry, The Threepenny Review, Hayden’s Ferry Review, Puerto del Sol, and elsewhere. She is an associate professor of English at Johnson County Community College. She holds an MFA in poetry from the University of Florida and a Ph.D. in English from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, where she was managing editor of Prairie Schooner and the African Poetry Book Fund. She is the co-editor-in-chief of Kansas City Review and winner of Frontier Poetry’s 2024 OPEN Prize. She loves writing poems and baking pies, and she posts images of both on Instagram at @asliceofpoetry.

✶

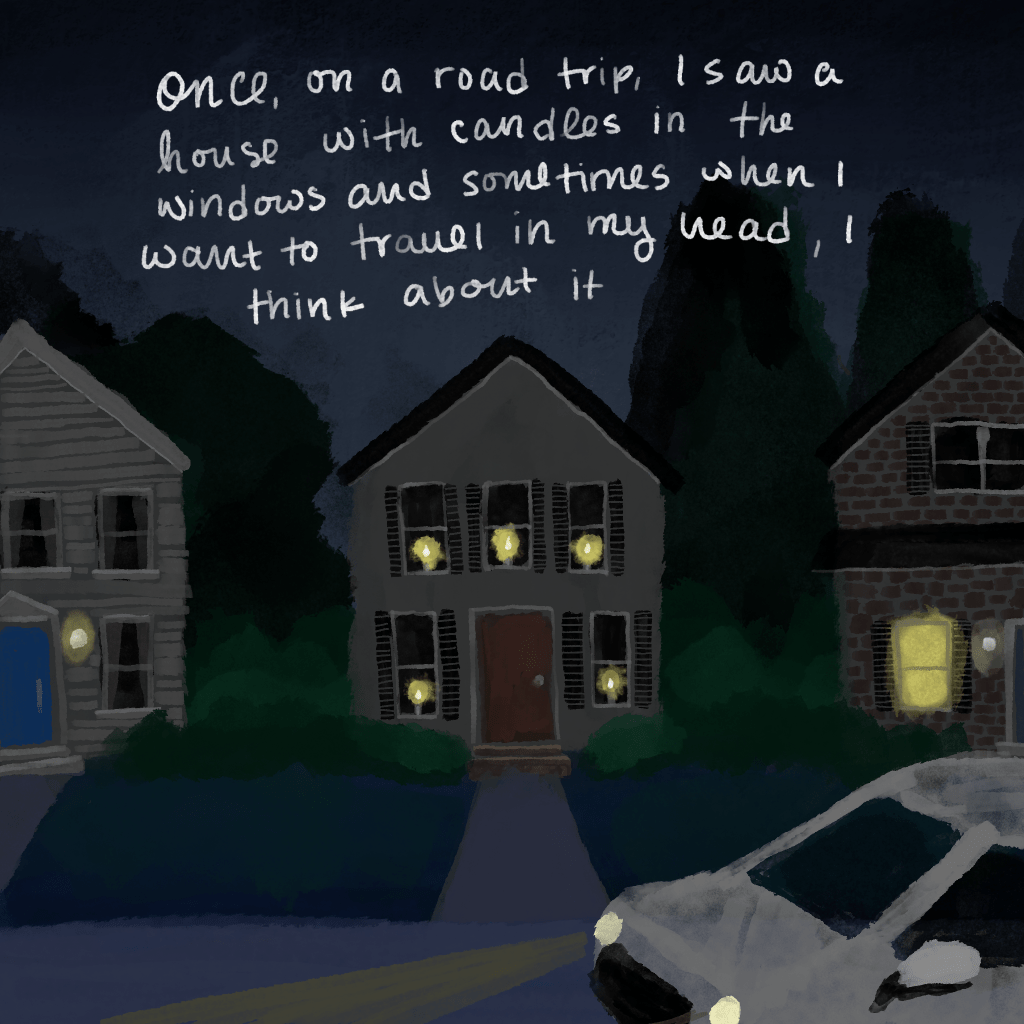

Cara Bloomfield runs a pictorial diary on Instagram called The Be Nice Comic. It’s a catalog of the universal and oddly specific ways she is human, a (semi-recent) journal of a new mother, and an attempt at capturing saliency in single panels.

✶