When Eid landed on a warmer month of the year, the three major Islamic community centers of northern New Jersey paused their microculture wars to apply for a park permit together. The park transformed into a carnival with food vendors, games, rides, and even a small petting zoo where children unknowingly played with the sheep they’d have for dinner later. Everyone dressed up as if Anna Wintour was hosting, and they were right to think there’d be a full review of who wore what. Mama said it was an opportunity to present yourself at your best to the whole community. That was code for: sanctioned mating ritual. These were the same people we’d grown up with, with occasional fresh blood from out of town. There might’ve been fish in other seas, but this pool was stagnant. Eid had always been the same as the one before it—until the year I started seeing ghosts.

Nothing else was out of the ordinary that morning. I couldn’t find anything to wear that wasn’t slutty. Everything I owned was suddenly too black and tight. If I showed up to the park like a whore at a funeral, it would be my actual funeral. The pile of clothing on my bed loomed large and undignified as I gutted my closet of options. I desperately tried to remember if I had ever dressed myself before.

“I’m in the car!” yelled Baba, who believed punctuality was the greatest sign of self-respect.

I’d stayed up too late the night before finishing a report on The House of Mirth, which was due right after Eid. Weakened by the spiritually-imposed lack of fuel and caffeine, I couldn’t stay awake long enough during the day to read more than a page, even though I couldn’t put it down the night before. I was gripped by the need to know how it all ended. Now, I had something of a nerdy hangover—disappointed, sleep-deprived, and without a single usable item of clothing. I threw the long black skirt I had been considering out of the way. The silky material, which had looked effortless and chic on the Hamdan girls last night but bunched up in unexpected places on my hips today, floated pathetically to the ground. My beloved tattered black jeans taunted me from their near-permanent spot over my chair. Mama would never let me anywhere near the park in them. As if summoned, she appeared at my door.

“Yalla Amira, your dad and Omar are already in the car!”

“Mama,” I chased her voice into the hallway. “Can I borrow something?”

Mama looked at me. She took her time. Her eyes dragged over my pajamas, a silent calculation of how many directions this next conversation could take.

“Let’s check my closet,” Mama clipped, relenting.

Everyone arrived early in the day, but not as early as Baba wanted. I surveyed the crowd next to Omar and my parents. Mama’s dress was uncomfortably tight. Did she pick this one to imply I gained weight?

She looked at me in that exact moment, as if she could read my mind. Could she read my mind?

“Amira,” she said slowly. “Khalto Rania and Talib are saying Eid Mubarak.”

Khalto Rania leaned in for three hovering kisses on alternate cheeks, her stack of gold necklaces swinging into my face. She stepped back, hands on my shoulders. “Mashallah, you’ve grown so much, Amoora!”

What a bitch.

“Thanks, Khalto, Eid Mubarak.”

“Eid Mubarak, habibti.” Khalto Rania looked expectantly at her son. Talib was still adjusting to his recent growth spurt, which had the unfortunate side effect of making all of his movements look like that of a drunk toddler. His hair was combed meticulously to the side, and he was wearing a light blue shirt tucked into a pair of navy trousers. I wondered if it was true that Rania laid out his clothes every morning.

“Eid Mubarak, Amira.”

“Eid Mubarak, Talib.”

“Eid Mubarak, Khalto, Khalo,” he said after a pause. We lingered unhelpfully in the moment until Omar recruited him for the soccer game beginning to form on the field. Omar was a basic Arab frat boy, concerned only with his boys and his business empire (imaginary), but he got along with everyone and always knew how to diffuse the tension in a room. People wanting proximity to him had served me well over the years.

Baba successfully drifted off without notice, probably to find someone to talk to about the structural integrity of the pop-up stage, since we hadn’t been a sufficiently responsive audience when he brought it up the first time. I could tell by Mama’s and Rania’s tilted heads and lowered voices that they were shit-talking someone nearby. This was also tradition.

“I’m surprised she’s here.”

“Haram, this is for everyone. Bil ‘aks, it’s good she’s here.”

“Poor Marwa,” Rania insisted. “Imagine raising a daughter like that.”

I followed their gaze to Marwa and her daughter, Dana, our very own cautionary tale. She was the season’s hot topic and it was only partly because the Ramadan shows sucked this year. Dana was less assuming than her reputation would have you believe. She was wearing a long, tight black skirt with a silver chain draped around her hips, a look I’ve thought about theoretically but knew deep down I could never pull off. Her dark, curly hair fanned wildly around her solemn face. She was a pretty girl that “tried to confuse you into thinking she’s not,” as my mother put it. She was standing next to her mother, looking as bored as I felt next to mine.

“I can’t believe they let her move to New York.”

“Sana told me Marwa’s sister-in-law told her that Marwa hasn’t convinced her to go back to school.”

“I heard she works at a bar,” Rania whispered.

Instead of going to college or getting engaged, Dana created a third option that none of us knew existed outside of TV. Some people said she dropped out of college because of an affair with a professor or a drug problem or to join a band or circus, all equally perceived as depraved paths for a young woman from an otherwise respectable family. I wondered if her parents forced her to come to save face.

“Her poor parents.”

“Haram.”

“You wouldn’t know who was more miserable, this troubled young woman or the people who can’t seem to cobble together a conversation about anything else.”

I looked around for the owner of this new voice that took the words right out of my head, an ally among the Aunties. My eyes glazed over then snapped back to possibly the palest woman I had ever seen. Her eyes bored into mine, sending a tingling sensation down my back that corrected my posture faster than Mama could shrill “Shoulder’s back!” I couldn’t look away. Her face was pallid, ill in an old-timey way, like she had died of consumption centuries ago. That was rude. What if she really was sick? There was something not quite right about her, though, but I couldn’t put my finger on it. She was wearing a long dark dress with puffy shoulders and a bulbous skirt. A bit much but sometimes the new converts took it too far. I suddenly locked onto the lace bib around her neck, something someone in deep Brooklyn would wear ironically but that felt out of place here. I felt panicked but I didn’t know why. Nausea knocked around my empty stomach with nothing to temper it. This woman looked just like the Wikipedia image of Edith Wharton I fell asleep to. Was I seeing pixels come to life? No. I needed to get a healthier sleep schedule now that Ramadan was over, it was clearly affecting my brain.

I took stock of what I knew. I chewed the inside of my cheek to confirm I was awake. I was at Eid. I was in New Jersey. This woman was dressed like a descendent of the Mayflower. She was probably lost, maybe dressed for a reenactment or something and saw conservatively dressed people gathering and got confused. Why was she weighing in on this conversation anyway? No one else seemed to be paying attention to her, so I took my cue from Mama and Rania and decided to ignore her as well. I was about to tune back into their conversation when two hijabi women, distractedly talking to each other, walked right through the Edith Wharton impersonator, without so much as a ruffle of her ridiculously large skirt. What the fuck was happening?

“That’s not exactly the language of respectable young ladies,” she said.

“What?” I whispered. Did I say that out loud? My skin was itching.

“Amira?” Mama asked, following my gaze and looking right through Edith. Edith?

“I’m going to get some coffee,” I said abruptly.

Mama smiled, nodding to Rania. “These kids stay up so late then act like zombies. They’re in for a big surprise when they have real jobs.”

“Tell me about it,” Rania commiserated with a tale of her own about Talib, but I wasn’t listening.

“I know what you’re thinking, but you must be smarter than that. Dana’s life isn’t one to aspire to, but you can learn something from her attempt at one,” Edith persisted, walking in step with me through the stands. Why would Edith Wharton be at Eid? If she was a ghost, I mean if hypothetically as a thought exercise she came back as a ghost, she would surely be haunting the Upper East Side and lamenting how much it’s changed, in a probably not not racist way. She wouldn’t be around a bunch of Arabs in New Jersey, wondering why they weren’t in the Ottoman Empire. This wasn’t real. She wasn’t real.

“I know your mother taught you to be a more gracious host than this,” she said.

I stopped at the mention of my mother, bewildered, overwhelmed, and now a little suspicious. “What is this?”

“-We’re raffling tickets for a number of prizes! For just ten dollars a ticket, you could go home with a five-hundred-dollar value authentic Turkish rug.”

Edith and I looked at the man whose stand we had stopped in front of—a fundraising effort for victims of the earthquake in Morocco. I hastily pulled ten dollars from the Eid money Baba gave me that morning.

“Terrible manners but at least you understand how important it is for a woman of means to remember those with less,” Edith said.

She was so pleased, I regretted the donation. Maybe I didn’t bite my cheek hard enough. This was lucid dreaming, or sleep paralysis, or whatever clinical horror exceeded nightmare. Mama was right. I couldn’t get away with staying up all night. If I had known this was the particularly wicked way it would catch up to me, I would have listened sooner.

“Overly romanticizing that young woman’s life is just as bad as gossiping about it,” Edith pressed on, unaware I had decided she was only a cruel, weird figment of my REM deficiency. “All she’s done is irrevocably blemish her family name. Look how people are walking the long way around to avoid greeting them.”

I watched as the Nakib family, famously generous donors, their hands first in the air at every fundraiser, detoured around a group of trees to avoid Dana’s family as they made their way to the auction table raising money for orphaned children in Palestine. I guess it’s easier to be charitable to people you don’t have to see.

I spotted Fatin and Hana near a coffee stand and walked briskly to them, hoping to lose Edith.

“Hey!” I said breathlessly.

“Amira!”

“Where’ve you been?”

Hana surveyed me, instantly handed me her coffee, and ordered another. “What’s up?”

“Nothing,” I said, as my eyes darted away from theirs. Edith was gone. “Didn’t get much sleep last night.” The coffee coursed through my body, shaking up dormant cells in its jittery wake. I wondered if I broke the spell.

“Anyway,” Hana drawled, intimating that she’d get right back to me. “So, Hamza texted me ‘Eid Mubarak’ this morning with a sad face emoji and I’m like, dude that’s so lame. I haven’t heard from you all month and this is your best move?” Hana and Hamza decided to pause their relationship during Ramadan, ostensibly for religious reasons, but I think they finally ran out of things to talk about. They’d been on and off since we were in 5th grade. Like I said, this pool was not connected to running waters.

While Fatin continued to be a better friend by lending a sympathetic ear, interjecting with alternating encouragement and caution, I squinted past them because I spotted Edith again. I was overwhelmed by the sudden need to confront her, to demand to know what was happening, to chase her away. How do you wake yourself up from being awake?

Edith was hovering over a woman’s shoulder, nodding along with theatrical empathy. My heart thrummed, and I couldn’t tell if it was the caffeine or the gnawing, subconscious knowing that this was not going away.

“He says he misses me, but I don’t know.”

“Was he missing you when he met up with Nisreen outside the mosque after iftar?”

Hana groaned. “Amira?”

From the corner of my eye, I saw my friends’ faces turn toward me, silent for a beat too long. I had missed my mark.

“Sorry?”

“What do you think about the whole Hamza situation?” Hana repeated.

I cleared my throat to buy time and see if my mind could surprise me for once in a good way by revealing I was subconsciously following the conversation. “There’s a reason he keeps coming back to you.”

Neither was pleased with this answer and, thankfully, they continued to litigate between themselves. I tracked Edith. She was getting a little too comfortable around a group of young men near the stage. What was it with guys and DIY construction?

Commotion was forming on the stage. The sound system was glitching, voices were raising in alarm. I watched a boy jump onto the stage and fiddle with the amps. I’d never seen him before and he seemed out of place with his shaggy hair, baggy jeans and floral-print button down. The speaker was brought back to life and he turned to the cheering crowd with a smile. I couldn’t keep my eyes off of him and neither could the Imam, apparently, who rushed to shake his hands. Who was this guy? I nudged Hana, who knew everyone, and asked about him.

“I don’t know,” she said in disbelief.

“I think that’s the new kid from Texas, Rana’s cousin. His family moved in down the street,” Fatin said.

“A bit obvious, isn’t it?” Edith was in my ear.

“What?” I flinched.

“Yeah, just down the street,” Fatin said. “I heard he only travels as far as he can get with his skateboard. Rana said he’s impossible to talk to, he’s like obsessed with death and writes about it on a blog or something.” She said blog like a slur.

“Rana said?” Hana asked, trying to triage the break in her social command.

“Are you trying to ruin your life? This young man is not suitable for you or the ideas in your head right now,” Edith said.

Get out of my head, you literal artifact.

“He writes?” I asked innocently, determined to ignore Edith. I had never met an Arab boy that was concerned with anything beyond school, sports, or entrepreneurship.

“Amira,” Edith warned.

“Ooh, he’s so your type, so moody and artsy,” Hana teased. “It’s just like that book I finished, the one I was telling you about? A classic nerdy-girl-falls-for-sensitive-bad-boy.” Hana lived her life in romance novels. Half the time she and Hamza broke up, it was because he couldn’t measure up to the ideal romantic lead of her latest read.

“I’ll see if Rana is doing anything later,” Hana continued. She was dying for a comeback.

“I’m down,” I said, as casually as I could muster. Hana was already texting and coordinating, back in her rightful place in the center of it all.

“What about that lovely Talib boy, Amira? He’s from a good family, dresses well, and has grand aspirations,” Edith posited.

Aspirations to wean himself off his mother’s teat?

“Amira!”

“Where should we go?” Fatin asked.

We decided to meet at a diner. Not the one closest to the park, but in the third town over, just in case. The way some of these Aunties used WhatsApp to keep us in check, I wouldn’t be surprised if the FBI watching all of us leveled up their skillset. Maybe then they’d realize the biggest threat to freedom was that we couldn’t even hang out with our own friends.

Shiny, sleek chrome wound around the curves of each retro-style booth, starkly reflecting the shimmer and glam of (some of) our outfits. I borrowed Fatin’s lip gloss and combed my fingers through my hair.

We took up two booths in the back. Hana, Fatin, Rana, and I claimed the innermost table, away from the window. Across from us sat Rana’s cousin, her brother, and their friend. We needed some time to shake off the feeling of watchful eyes at the park. We ignored the boys at first, chatting among ourselves as if we were seated next to strangers. The shift, when it happened, was imperceptible. If you weren’t paying attention, you’d miss it. It could go down in a number of ways. Someone might have to leave the booth to take a call, go to the bathroom, show someone from the other table something on their phone. Divine intervention could deliver an order to the wrong booth. The spell broke and suddenly, Fatin and Hana were at the boys’ table, and Rana and her cousin joined ours. When it happened, you couldn’t acknowledge it. You had to be cool.

“So what’s Texas like?” I asked coolly.

“Texas?”

“Yasine just moved from Ohio,” Rana said.

“Ohio, Texas, New Jersey—what’s the difference?” Yasine asked, dragging a cold fry around his plate, drawing all of our attention to it as he collected salt and ketchup before taking a bite. “If it’s a decision that’s imposed on you, not your own, what’s the point of having an opinion on it?”

“Wow—”

“—Wow,” Edith and I said at the same time, but she was rolling her eyes. I had hoped her presence was somehow anchored to the park, but seeing her here, inside, so close to Yasine, I knew this was becoming something outside of any bounds. How did she find me here?

“I followed the scent of hormones, desperation, and terrible food,” she said.

The unfortunate truth of that moment was how jealous I was of how closely she, an unreal person, was seated next to Yasine while I had a whole table between us.

“This boy is a nihilist and even worse, a bore. This is not the sort of young man that will make life easier for you.”

What could she possibly know about the life I wanted? She looked haughtily at my burger, reminding me of my mother’s unwavering attention to my plate. I bet Edith never had a burger. She must be starving. No wonder she looked like that.

“Never thought about it like that,” I responded to Yasine.

“We should all be thinking in ways we never have,” Yasine said.

I accidentally met Edith’s triumphant eyes.

“I heard you’re a big reader,” he continued.

“Oh? I don’t know.”

“What are you reading right now?” Yasine asked. He was looking at me again. I thought his eyes were brown at first but the longer I held them, the more I could trace a soft hazel glow around each iris, a rich honey.

“Anna Karenina,” I said. I knew this made me sound like an asshole. “It’s not as intimidating as it looks. If you skip the farming parts, it’s basically a Russian reality show.”

“I’ve never read it, but I’m into his other stuff. Maybe I could borrow it when you’re done?”

This was the sluttiest thing a guy could say to me.

“Sure,” I said.

Rana had drifted to the other booth, leaving Yasine alone with me, and Edith. It was hard to look directly at him, mostly because I ended up looking at Edith too.

“I heard you’re a writer?”

Yasine smiled—too brightly for a nihilist, Edith, don’t you think? “I don’t know about writer, but I dabble, yeah.”

“What kind of stuff do you dabble in?”

“All kinds, I just posted something on Pan-Arab futurism in a post-capitalist world on my website.”

“Is he having a stroke?” Edith asked.

“I’d love to read it sometime.” I didn’t know what he was talking about either but I hoped I sounded convincing.

“Oh, I don’t know, okay, man, but don’t judge me too harshly,” he smiled, and I couldn’t tell if he was pleased I was interested in reading it or just that anybody was. Fatin’s “blog” reverberated in my mind.

“I’ll text it to you. What’s your number?” The tips of his fingers grazed my hand as he slid over his phone. I ignored the goosebumps that danced up my arm, crashing like the gentlest tidal wave in my chest, aftershocks raising warmth to my face. I kept my face down while I typed my number out slowly, as if I barely wanted to.

Suddenly, Edith was on my side of the booth. “Should you really be giving this young man unfettered access to you?” She asked leading questions in the same way my mother did.

You’re being so dramatic. I can ignore him anytime.

“Can you?”

I’m not fighting with a ghost.

“Can you?”

Shut up!!!!!!!

I instinctively took my phone out to save Yasine’s number only to see five missed calls from Mama, two from Baba, and a slew of warning texts from Omar. The wave dropped in my stomach and flattened.

I stood up abruptly and realized Yasine had been in the middle of saying something. His voice faltered to silence. I walked to the next table and asked Fatin to drive me home. She was deep in conversation about the merits of going to Rutgers for college and saving money by living at home, even though we all know her dad bribed her with a car to avoid dorming. Whatever my face looked like made Fatin immediately grab her keys. I didn’t even say goodbye.

“What happened?” she asked as we headed to her car.

“Someone saw us.”

“You sure?”

I handed her my phone so she could see Omar’s texts.

>Heads up

>Mama and Baba know you’re on a date

>They’re pisssssed

>Go home so they stop calling me damn

“Date?” Fatin was incredulous. “What about the rest of us?”

I replayed the scenes my own personal FBI informant must have seen. I tried to narrow down my worst offense. How long were we sitting by ourselves? What did my face look like when he asked to borrow Anna Karenina? What were the odds that the first time I ever touched a boy’s hand was witnessed by an Auntie with a direct line to my parents?

I sat silently in the passenger seat, tapping my foot nervously against the door.

“—I can explain we were all there, it was my idea, Rana’s cousin just happened to be there, we don’t even know him, which is kind of true actually.”

I realized Fatin had been talking this whole time. We were already at my house. I assured her I would be fine and jumped out of the car, overtaken by a strange restless energy. I felt every hour I hadn’t slept but instead of feeling ragged, I felt alive. My skin was vibrating. I waved to an increasingly concerned Fatin and paused at the front door to smooth out my outfit. Fuck, my mom’s outfit. I fraternized with boys in my mother’s clothes. If anything, that should reassure her that nothing inappropriate could have possibly happened. That it was an act of God himself that a boy even talked to me dressed like this.

The house was quiet. I steeled myself to find my mother, father, brother, and up to three uncles lined up to read my offenses. What made it worse was having to search for them.

“Mama?” I called out, slipping out of my shoes and padding into the hallway.

“In here, Amira,” Mama called from the living room, the worst place she could have been.

We did not spend time in the living room. The living room was where we impressed strangers. It was the first stop to enter the house so it set the bar. The closer you were to the family, the deeper you were invited to other parts of the house. The dining room was reserved for special occasions. The family room was where we actually did our living. But we were our truest selves in the kitchen, standing around the counter, nibbling on whatever Mama had thrown on the stove or sipping tea, gossiping about the people that wouldn’t even make it past the dining room.

I gingerly stepped into the room. I couldn’t meet my parents’ gaze yet, tracing the pattern of the rug with my toe while I tried to think of how to start. I knew if I could just explain the situation, they would understand.

I opened my mouth to begin my testimony when I caught Edith on the couch behind my parents. Nonono—

“The more you try to explain yourself, the more you’ll need to.”

What did she know?

“Amira, what have you done?” Mama started instead, somehow already on the verge of tears.

I looked down. This rug had actually been the second choice for this room. The original rug intended for it was downstairs, tightly sealed, waiting for me. I was nine when my parents first brought it back from Turkey and apparently, I was obsessed with it. Baba loved reminding me how he would periodically find me laying on the rug, cheek pressed to the plush, marveling at how beautiful the swirling shades of red were. He promised it was mine once I had my own family and rolled it back up for storage. I had initially been pleased, but as I got older and understood how time worked, I realized how much more of it I had ahead of me. A few years later I asked Mama if I could still have it if I never got married. She said if I kept talking like that people would think I was a lesbian. For a while, this convinced me I was a lesbian.

“Amira!” Mama said and my eyes snapped up.

I’d never seen them look at me this way before, like they were seeing me for the first time.

“Who were you with?” Mama said, exasperated.

“What’s his last name?” Baba was ready to take it up with the elders.

Mama tsked at Baba for deflecting from her line of questioning.

“Amira? Who is this boy? Since when do you lie to us?” Mama’s eyes sparkled. I hated that she was such a pretty crier. I figured I cried like Baba but I didn’t know for sure. I witnessed him cry only once, when his father died suddenly and he couldn’t afford the quickest flight through Amman to Jerusalem to make it in time for the funeral. In my splintered memory, we’re in the kitchen with his back to us, pretending to do the dishes. No one acknowledged it, but we all knew he was crying, and we let him be.

“Who have we raised?” Mama asked, the tip of her perfect nose turning pink. I knew it was over when she started blaming herself.

“No, Mama, I swear, it’s not like that! Rana brought her cousin with her. I don’t even know him!”

“That’s how you act with someone you don’t even know?”

“We were just grabbing food! Everyone was there!”

“Who’s everyone?”

I listed them all. I made sure there was an odd number of girls and boys to avoid it seeming like a massive group date. I would rather my parents thought I was on a date with a boy than think I was a loser who went on group dates. Someone’s brother was there. Nothing that interesting could happen with a brother around.

“Why wasn’t it your brother?” Baba asked unreasonably.

“Amira, what were you thinking?” Mama repeated.

“I’m sorry,” I said. How could I explain to them the rush of meeting a guy I couldn’t believe was real? They would never understand. To them, love was practical. A business decision.

“Do you think it was worth it?” Edith asked. “To ruin your reputation?”

Ruin my reputation? This isn’t the eighteen-hundreds.

“What will people think?” Mama asked. “How will they think we raised you?”

I wondered if Yasine was worth it. His curly hair fell into his face in an adorable but probably secretly high maintenance way. He seemed like the most well-read person I knew or did he work really hard to make it seem that way? What if he hated Anna Karenina? What if I hated his writing? I had a terrible poker face. He was a senior and would probably be leaving soon, this strange little place a stop over on the way to the rest of his life.

“I’m sorry,” I repeated. And I truly was, because I lived completely tethered to my parents. Everything I did was an extension of them and, now, I had embarrassed them.

“Crying now will just make you look more guilty, my dear,” Edith said softly. It was a bad sign that she was being nice to me.

“Go to your room. We’ll talk more later,” Mama said, pinching the bridge of her nose. If that was the worst of it, it wasn’t so bad.

“Leave your phone here,” she added.

I landed on my pillow, face first, and screamed. I experienced the worst day of my life in an ill-fitting outfit that constantly reminded me of my mother. I laid still over my duvet. I didn’t want to change or go to the bathroom and risk running into anyone in the hallway. I desperately wanted to sleep but my eyes were alert. I reached for my phone to check the time but remembered I left it downstairs.

I checked the time on my laptop. 6:43pm. Early curtains for the last night of my social life. The computer automatically logged me into the chat and the window pinged as a flurry of messages came in. I slammed my hand down on the keyboard to mute the speaker and waited, frozen. I strained to hear any movement from downstairs. I was in the clear.

I returned to the screen. I scrolled past “checking in” texts from Fatin and Hana and settled on a set of messages from an unknown number.

>Hey, its Yasine

>(Rana’s cousin)

>You good?

‘(Rana’s cousin)’ was adorable. He had no idea the lengths we’d conspired to meet by chance at the diner.

<Hey! All good

<Sorry for the dramatic exit lol

I stared at the screen for so long, my eyes blurred it into a white canvas I could project all his imagined responses onto. They were all devastating. I blinked my vision back into focus only to see my own texts. No response. I pushed the feeling down, down, down and opened up a new tab and typed out his name.

Yasine Naffar. Writing out his name made my heart race in a way I thought only existed in Hana’s romance novels. The first few hits were social media accounts with the same username, a play on his last name, “naffs,” meaning soul. It was objectively corny. Right?

I scrolled quickly through a lot of content on philosophers, some I’ve heard of, others I couldn’t pronounce. I clicked into his website and a Pink Floyd song welcomed me in. It seemed a bit overkill for a high school senior to have their own website. Unchill, even. Against a black backdrop, a neon graphic appeared of two lines of text moving in opposite, concentric circles, one in English and the other in Arabic. “A person can only be born in one place. However, he may die several times, elsewhere…”

I couldn’t tell if he was the smartest person on Earth or a complete loser. Not knowing where else to click, I selected the moving circles and surprisingly, a menu appeared. Me, Content, Contact. I clicked Me. It was a trap. There was a single line of text that read, “Who do you think I am?” with an open text box for submission.

Embarrassed, I quickly clicked Content and it returned a collage of moving photos stitched with links to articles and images and titles. My eyes glazed over, not knowing where to land. I found the link to the Future Pan-Arab-whatever he posted but I paused and thought about it for a second too long. Did I want to know?

I imagined us in a cafe in New York City. I was dressed in a stunning black beret over a chic, smooth, frizz-free bob, offering a gentle but incisive critique of his novel while he took notes, looking at me with big, adoring honey eyes behind wire-framed glasses.

A ping from my computer startled me out of my head. I reflexively minimized his website. Fatin said that if you suddenly remember to text someone back, it was because they were stalking you on the internet. Personally, I thought it was too late for new wives’ tales.

>Haha yeah you seemed stressed

I hesitated then clicked back into internet-Yasine. It felt safer here.

I clicked Contact. I should have started with this because he linked every possible social media account. I clicked into one I hadn’t seen yet and came face-to-face with those hypnotizing, haloed eyes. They reminded me that you could be a little embarrassing on the internet if you’re good-looking enough. I scrolled back to his photos in Ohio. I don’t know what I thought Ohio looked like because it looked a lot like New Jersey. Maybe he had a point about the nihilism.

I scrolled back up and noticed he posted three minutes ago. That must have been why it took him ten minutes to text five words. I clicked to enlarge the photo: a flier for a band’s pop up show in New York. The caption read “Come see @DanDanDrum kick ass in Brooklyn for a secret show tonight! DM for details.”

I clicked the tagged profile and craned my neck, the tip of my nose nearly touching the screen but I could only see Dana’s tiny profile picture, the rest set to private. I clicked back to Yasine’s page and combed through for more possible connections, my heart beating in my ears. I found a photo I must have scrolled past too quickly. Two weeks ago, he posted a photo of the back of a woman in front of a stage, bright lights outlining her wild hair and the drumsticks in her back pocket. The caption read “Birthday Bash.” I googled the zodiac sign for two weeks ago in April and then looked up my compatibility with Tauruses. Not great.

I replaced Yasine’s name in my browser with hers. All her social media was set to private. I found a write-up about her band from a small online music zine. The post described a fantastical, burgeoning art scene in Ridgewood. Art! Taste! Youth! There were people “bursting onto the scene” fifteen miles away from me while I sat hunched over my laptop in the dark because I was grounded.

I leaned back on the headboard and closed my eyes, wondering what it would feel like to have Dana’s bouncy hair, the smoothness of drumsticks in my hand. I was at a show, rocking back and forth on a stool—a musical prodigy, enthralling the rapt audience with my raw talent. I would go home at night to my own apartment in a cool but overlooked neighborhood. It was artfully decorated but I was never there, roaming the streets of New York without a map, knowing the subway stops by heart but letting myself get lost anyway. I blended into an anonymous crowd, no one looking at me or setting a curfew or grounding me. I answered only to myself. I wore my own clothes.

I texted Yasine back.

>What are you up to tonight?

From an unseen corner of my darkened room, I could hear the unmistakable throat clear of an unwanted, interjecting opinion.

✶✶✶✶

Bayan Adileh lives in Brooklyn and is working on her first novel.

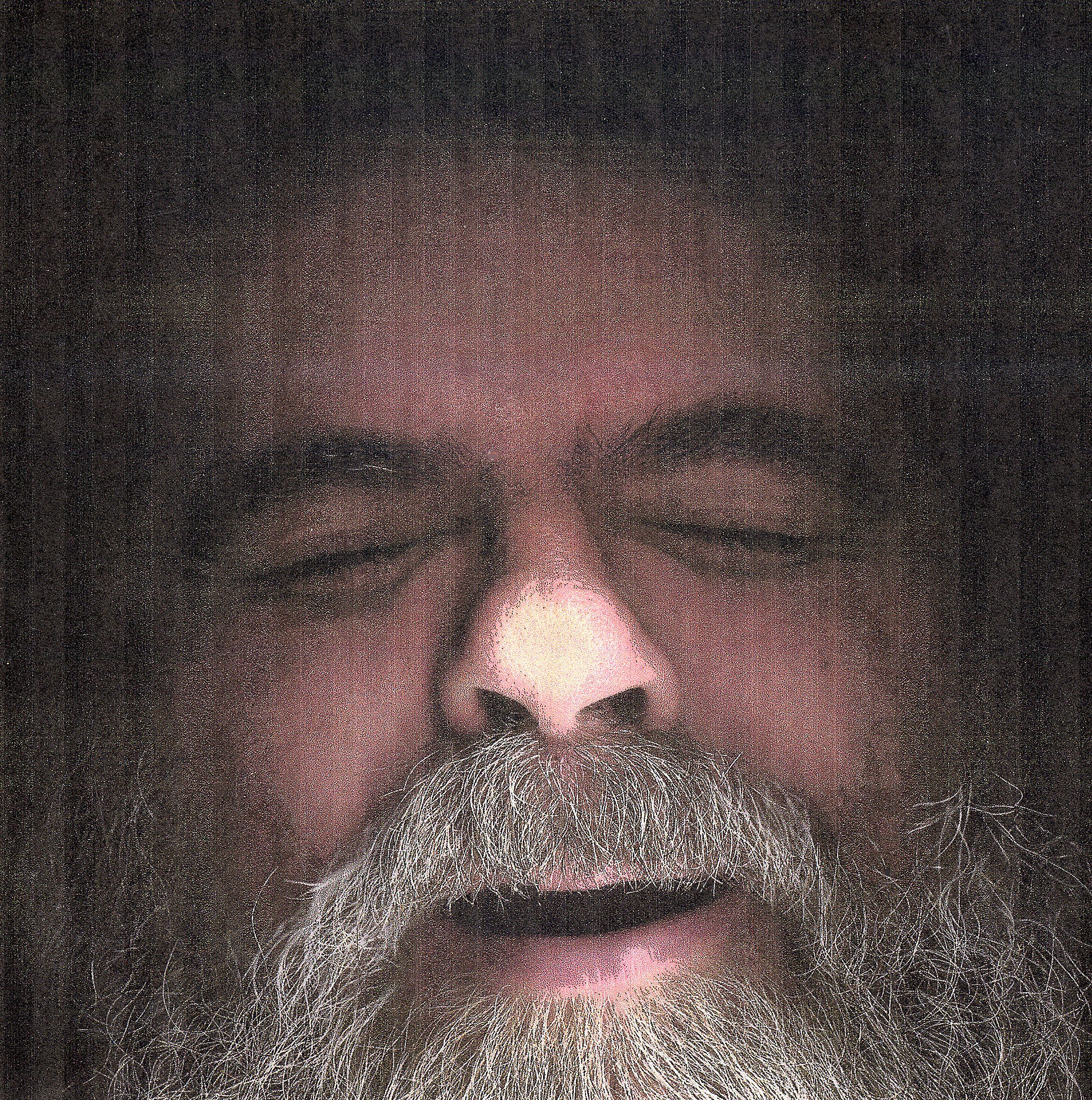

✶

Originally from New York City, Robert Bharda has resided in the Pacific Northwest for forty years where he has specialized in vintage photographica as a profession, everything from daguerreotypes to polaroids. His digital “Quantisms” originate from templates composed of all organic materials (mushrooms, leaves, flowers, seashells) and seek to release dynamic motion from fractal potential. His illustrations, artwork, and photography have appeared in scores of publications, including Naugatuck River Review, Catamaran, Cirque, Northwest Review, Blue Five, Superstition, andAdirondack Review. He is also a writer of poetry, fiction, and critical reviews published in 100+ journals and anthologies.

✶