He could look down the hill at masses of people carrying signs, hollering. They were angry, Troy was angry. The crowd shifted and reconfigured itself as a unit, and when the speakers asked for silence the crowd complied. Troy sat on the blacktop while the emcee, a middle-aged community organizer in a tweed jacket and blue jeans, shouted into the bullhorn.

“We see these policemen over here…” The intersection above them was lined with uniformed police in crowd control gear. “…surrounding our demonstration. They say they’re here to protect and serve, but who are they protecting? Who are they serving?”

The crowd bellowed discontent.

“They don’t protect me. A cop has never had my best interests in mind. They serve people who have money. They protect property. Today, they’re here to restrict us, oppress us. They say they’re here to defend free speech, but our speech isn’t protected. In reality they’re protecting fascists who should never have been invited to our community. White fascism is a plague in our nation right now, threatening our liberties, and these police are just the enforcement arm of that ethos. They are de facto white supremacists.”

✶

Reporters stood from news vans and filmed the rally. Scanning the crowd, Troy noticed the barista who used to work at Pergolesi. Back when he’d been hip and felt himself relevant, Troy had fallen in love with Audrey. So many evenings together out at the bars. To whatever degree he’d been capable, Troy would have committed himself to her entirely, but Audrey had only kissed him once. They wrestled drunk at 3am in a shore-side park along East Cliff, and Troy had accidentally split her lip and then she kissed him.

“Holy shit, it’s been ages.”

“I’m so sorry.” She looked at him with apprehension. “Where do we know each other from?”

Troy paused.

“I was a real mess when I was younger.” Audrey shrugged.

“So was I.” The interaction ended, auguring a future in which memories of Audrey— once frequently and fondly revisited—were reconstituted as pain. A future that, in one more way, reminded him of his own smallness, the insignificance of his existence in the lives of others.

✶

“… Police have been killing our young black men and women, our young brown brothers and sisters, since this country began. America was founded on the blood of black and brown people, and that fact has remained constant for six hundred years. Poor white immigrants were hired as police and given a mandate to control runaway slaves, thus pitting poor against the poorer. After Reconstruction, these same officers continued to arrest and imprison freed black men in order to perpetuate a penal, carceral form of slavery. They’d been knocking heads ever since.

“White America might never have realized the extent of these contemporary lynchings, these extra-legal killings, if it were not for the invention of the cheap digital video camera. But now we have video evidence, my friends, and since Rodney King, we have at least a modicum of national outrage…”

A young woman with a black T-shirt took the bull horn. “Whose streets!?”

“Our streets!”

“Whose streets!?”

“Our streets!”

“Whose streets!?”

“Our streets!”

✶

There was movement from the police, reinforcements arrived. They formed a line from sidewalk to sidewalk at the top of the hill and the reporters and news vans disappeared behind them. In formation, shoulder to shoulder, the police held their clubs out somewhere between waist and shoulder height, with a second flank of officers adding muscle to the first and then more scattered in line behind them.

Those with bullhorns shouted to the protestors. “They’re trying to move us, but we shall not be moved. We will stand our ground.” Troy was at the front of the crowd, pressed up against the wall of police. The protestors locked arms in a line, facing the cops.

Troy looked dead into the eyes of the cop ahead of him, though the man refused to meet his gaze. Troy hunted for humanity there, looking for the man who went home to his family each day, who had emotions and desires, who was frail but also, hypothetically, wanted good in the world.

But this was just shallow idealism, because he’d personally known so many men who didn’t want or care about any good but their own. Earlier that summer, a protestor, a young woman, had been murdered by a motorist who dodged police barricades to drive through the crowd. When Troy heard about it, he was working on tugboats, towing a fuel barge along the Aleutian Chain, and his captain had applauded the murder. Captain Greg acted as if the protestor deserved death for standing up to the world, for insisting on racial equity.

That captain and so many other of Troy’s crewmates spoke like this. These men never failed to disappoint.

And because he knew and lived with these men, understood their rage and hatred, Troy felt he also had some understanding of the cop’s psyche. And the fissure in his heart was agitated ever so slightly, as Troy succumbed further to the slow death of disillusionment, and he stifled tears in an already charged atmosphere.

Troy vowed to hold firm against these police, but when their orders were barked aloud, each officer took a step forward in tandem. Troy felt the pressure of the crowd behind him holding their ground. The woman on the bull horn shouted it: “Hold your ground! These are our streets!”

Troy did hold his ground with the rest of the crowd and continued looking the cop in the eye. Bodies came in contact and Troy used every means to anchor himself in place, creating a wall with which the officer was forced to reckon. That cop would have to push Troy and with the next police command, with the next step forward, the officer did push him. Troy didn’t move and the cop kneed him in the groin.

✶

Antifa joined the protest, women and men of various ages and sizes wearing black in different configurations—black jeans, T-shirts, sweatshirts, denim jackets, work boots, Converse, stocking caps, baseball caps… The clothing was hip-looking, tough, identity- generated through variation within that uniformity. But the purpose of the costume was anonymity, and all of the Antifascists wore masks—mostly black bandanas.

Because Troy had attended a liberal arts school that allowed for radical anarchism, he had friends join antifa before the group became a media presence. So it seemed out of nowhere, they were being referenced on 24-hour news cycles, lambasted by politicians, painted as domestic terrorists. Troy understood these broadcasts for what they were—a distraction, a scapegoating. And it worked. Even progressives looked at antifa side-eyed.

The police pressed the protestors backward down the street, inch by inch. Another flank pressed the throng downward from the hill opposite Troy, crowding the protestors into the intersection. Thousands of protestors forced into that small space, roads blocked at either end, the march obstructed by a line of police.

But then, as if by command, the Black Bloc—all those young anarchists with their faces covered—converged on one of the police barricades, pushing against that wall of masks and shields. And they were making progress, forcing the police back, inch by inch.

As the barricade splintered, individual police put up less of a fight than the force had as a unit, retreating to the sidewalks as the crowds poured through. Antifa achieved what the authorities had attempted to suppress: the protest itself. The organizers found their place towards the head of the march, and led the group through the city.

✶

“Whose streets?”

“Our streets!”

“No justice.”

“No peace.”

“No racist.”

“Po-lice!”

Walking block after block of the city he loved, Troy ran into friends and acquaintances. He loved that place with a ferocity so deep that he felt duty-bound to fight for it.

“Rrecall the name Kayla Moore, who died neglected in Berkeley Police custody. What about Yvette Henderson, the grandmother of four who was shot dead with an AR-15 assault rifle by Emeryville Police? Or, Teo Valencia, shot in the back by Newark police with the very same military style weapon.”

There was another group of protestors waiting at the university plaza when they arrived. Speakers rallied from a makeshift lectern: “And we have invited our allies here, the Black Bloc, to act as a security arm for our purposes today. We do not advocate violence, but we recognize the possibility of it, and hope that antifa will ensure against that—both at the hands of the police and the fascists who have organized this rally today.” And with this reference to their presence as a cue, all of the young people dressed in black masks and black combat boots formed a phalanx at the edge of the park. Antifa looked like they could threaten this awful system.

But it wouldn’t be necessary. The marchers discovered that the right-wing assembly had been cancelled. And though the protestors celebrated the power of the collective voice—they’d driven the fascists out—Troy foresaw the media representations of the march: the claims of violence and vandalism.

He foresaw so much more: the destruction of the world, the gradual melting into the abyss, the waves and the droughts and the hurricanes and the fires that would reclaim them all. The police were just one symptom. Troy could see what was already happening, the grand extinction, and he understood that hate buttressed an environmental and economic reckoning. Deployed by those with too much power, hate generated complicity.

✶

There were already claims on social media that the fascists would have numbered in the thousands if their legal rights to assembly had not been revoked—they were the oppressed ones, their free speech threatened. In reality, it was clear the event was bound to be poorly attended. It would have been an embarrassment. The fascists had sold few tickets in advance, and this community despised them. The whole point, all along, was the lie constructed in the aftermath, a lie that legacy media seemed so eager to perpetuate: violent left-wing suppression of right-wing First Amendment rights.

And to that end, despite the assembly having been cancelled, several right-wing agitators did arrive. They made their presence known, martyrs for a cause they believed in—a cause that would catalyze and ensure their own ascendance and dominance, so long ignored or forgotten.

These men antagonized the protestors from behind a wall of police, screaming about the legitimacy of police violence, about the culpability of black victims. And the Black Bloc responded by pushing against that line of police, demanding access to the men sheltered therein. And when, inevitably, the line of police was broken, and the fascists were no longer protected, antifa attacked them.

Troy was to the side of the square when violence broke out in front of him. A large, bearded man had been fleeing the antifascists. He was wearing a black polo shirt and camo khaki pants, and he covered his head and screamed as he was bombarded. Five members of the Black Bloc had surrounded the man and were punching him in the face and head—wherever they could make contact.

It wasn’t long before he was bleeding. He fell and the antifascists began kicking the fascist. Troy watched those boots choreographed to the harmonies of an angelic choir, as if the destruction of a man’s face, the buckling of a knee, were the logical dramatic event in a divine masterwork. Troy felt blood pulse through the finest of capillaries as his heart rate spiked and pupils dilated. His hands clenched to fists with the self-righteousness of a man untroubled by his own convictions.

And Troy acted then without rationalizing or processing. He dove in front of the man, grabbed him from under the arms and feet of his attackers, and hoisted him to his feet. The man was crying. His face was swelling in places, and it was clear he’d fared worse than he’d anticipated. He didn’t thank Troy or the other protestors who ran to protect him.

Before long, they’d formed a ring around the fascist, and ran with him to the police so that he wouldn’t be beaten any longer. Antifa didn’t question those protecting him, nor did they try to take the man back. When Troy first grabbed him up, the anarchists punched at the man over his shoulders. But that was all. And in that way, Troy helped to save a white supremacist from greater harm.

Troy did not leave the protest a proud man. He didn’t think he’d been righteous or justified in protecting the scum. He recalled again the way his captain had celebrated the death of the protestor. In that man’s mind, peaceful activists deserved death. Captain Greg wouldn’t have pushed her from the car’s path.

✶✶✶✶

Ben Leib has a master’s degree in literature from the University of California, Santa Cruz and a teaching credential in English. His work has been published in over three dozen literary magazines, the most recent being Emrys and Little Patuxent Review. He also has a bachelor’s degree in Marine Transportation, and now captains a tug boat in San Francisco Bay.

✶

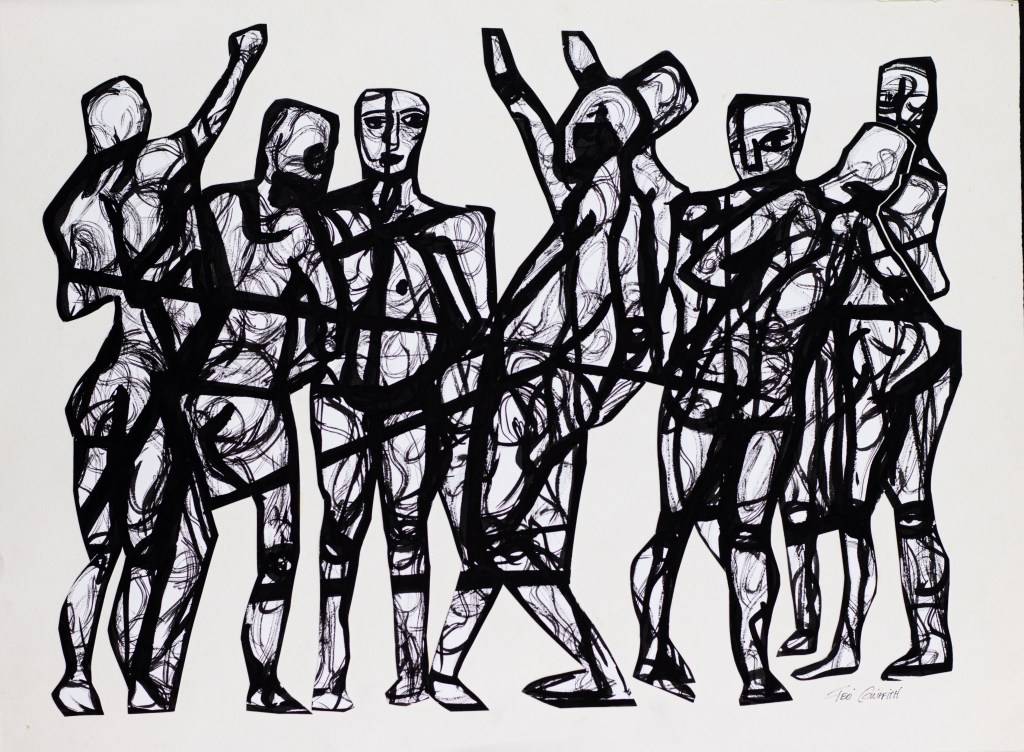

A native of Wisconsin, Jeri Griffith is both writer and artist who grew up in the Midwest. She regularly publishes essays and short stories in literary

quarterlies. Many of these can be accessed through her website and read

online. Her artwork—paintings, drawings, and films—can also be viewed on

her website. Jeri lives and works in Brattleboro, Vermont with her longtime collaborator and husband Jonathan, her best friend Nancy, and their two beagles, Molly and Ruby.

✶