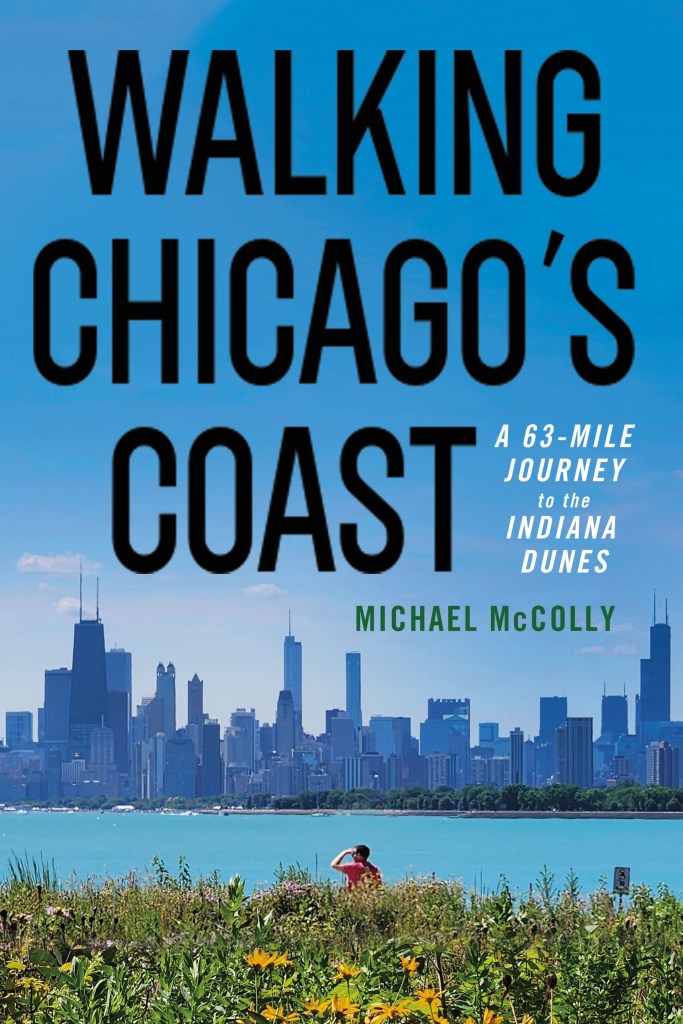

Blending travelogue, memoir, and environmental reportage, Walking Chicago’s Coast takes readers on an urban journey. Michael McColly begins his walk at his far–North Side Chicago apartment and proceeds for two long days along the shore of Lake Michigan to the Indiana Dunes National Park. As he walks, McColly reflects on the layers of history, the constructed magnificence, and the troubling divides in this polyglot mecca of the Midwest. From its descriptions of grand parks and architecture to packed sandy beaches to polluted neighborhoods called “sacrifice zones” along industrial waterways and rivers, Walking Chicago’s Coast shows how such urban hiking lets one contemplate a city’s grandeur and history, confront environmental and social realities, and trigger emotions and memories. Through Superfund sites, brownfields, scrapyards, and industrial ruins, McColly discovers the remarkable patterns of urban nature and the surprising beauty along his path.

British Petroleum’s Refinery, Whiting to East Chicago, Indiana

For a moment I just stand there with my hands on my hips, looking at my pack and then down the road lined with oil depots. It’s going on nine o’clock, and I’m not sure where I am or just how much farther I’ll have to walk to get back to the shore and the casino complex. If I had any sense at all, I’d head back to Hammond and find a cab to take me to some Super 8 or Motel 6, call it a day and start fresh the next morning. But pride and extreme fatigue win out over rational decision-making. I pick up my gear, cross the road at the light, and head into the bright lights of BP’s refinery.

Crossing four railroad tracks, I pass Happy Jack Liquors and a row of wooden houses near BP’s gates, wave to an old man sitting on his porch smoking a cigarette and hope I’m heading in the right direction. Behind the row of houses, ten-thousand-gallon oil depots, their crowns lit with cherry-red blinking lights like giant cupcakes, extend one behind the other into the humid, oily darkness. Ahead are more depots and a clean, well-lit field station, all behind a ten-foot chain-link fence.

On the other side of the highway, encased in pipes and scaffolding, dozens of distillery towers stand like a gargantuan flaming pipe organ against the darkened skies over Lake Michigan. From the ground, it feels as if I’ve entered some science-fiction fantasy land dreamed up by Dr. Seuss: pipes four abreast snake along the ground and then disappear into the brown sandy earth or bend at right angles and cross the road overhead. Amazingly, an employee in bright green jogging shorts takes off down the sidewalk, apparently out for his evening run, making me feel a bit better about what I might be breathing. But it can’t be healthy to work, let alone exercise, in a place where workers are warned as they enter by blinking digital signs: DO NOT BRING IN LIGHTERS OR CIGARETTES. One match and me, the jogger, and the guy on the porch could be blown to bits along with those on the night shift. I’m aware as those who live around this facility should be, not to mention its employees, of the company’s history of explosions and deadly accidents. BP was not only responsible for the eleven workers whose bodies were never found on its offshore drilling platform in the Gulf in 2010, but in 2005 its lax safety standards caused a massive explosion at its refinery in Texas City, Texas, that killed fifteen workers and injured some 170 others. Two years after the incident in Texas City, OSHA found that the oil giant had not corrected its violations and still had seven hundred safety hazards, resulting in the stiffest penalty ever handed down by the federal agency against a corporation.

From up close the distillery towers no longer appear as hazardous and horrific, but instead trigger my boyhood fascination with the mechanics and chemistry of oil refining. What’s taking place here in this surreal landscape along the lake? Whether one is a child or an adult, the process of turning fossilized plant matter into gasoline, asphalt, polyesters and paint, solvents and kerosene, jet fuel and any number of other products can capture the imagination. Who wants to imagine the degradation of forests, or ecosystems millions of years in the making being ripped open by bulldozers bigger than a two-story house, when one can instead try to fathom how engineers can design machines to hoover up tar sand and send it along thousands of miles of pipelines with just the right mix of chemicals to keep it flowing, under rivers and even along the floor of Lake Michigan? Here, in this sci-fi fantasy come to life, these rocket-like distillery towers before me boil a stew of ancient sea creatures and trees at 800 degrees Fahrenheit and miraculously filter out the impurities to make regular, premium and super unleaded for you and me to buy and burn.

A teenage Black boy rides by on his bike and then in the other direction a white girl, their bikes like horses in a pastoral scene of ages ago. Allies, I think, as they glide by, their bodies floating over the road, their legs pumping through air thickened by benzene and particulate matter. Both turn and glance back at me as they pass, in wonder, I imagine, at who might be walking with a backpack through their territory of teenage freedom. “To be is to be perceived,” the metaphysician George Berkeley observed, and their acknowledgement lifts my spirit and sends me deeper into the edgelands of industrial Indiana.

The oil depots ended a few hundred yards back, and I’m walking along a mysterious ten-foot wall of fire-proof material. Behind it, adding to the intrigue, stretches an earthen wall that parallels the fence. Yellow signs every couple of hundred feet read: WARNING, US GOVERNMENT, NO TRESPASSING.

At first, I think it’s just another of the many Superfund sites that dot the region, which would explain the fence and the telltale pipes sticking up out of the top of the wall of dirt. But squinting far ahead, I can see a small bridge under two towering streetlights. And now I know where I am: I’m circumnavigating the future home of tens of thousands of tons of toxic sludge that the Army Corps of Engineering will dredge up from the nearby Indiana Harbor and Ship Canal and then dump here at this enclosed site. I’d seen this very hellhole from above the day before on Google Maps.

I stop as I reach the center of the bridge and look down into the brackish blackness of the canal twenty feet below. A snaking boom holds back a sudsy scum with bits of trash; behind it floats a sheen of oil. Thickets and trees hang over one side of the canal, and on the other there’s another earthen wall to ensure, theoretically at least, that PCBs and other toxins won’t leak into the canal. But the lights atop the wall reveal a drainage pipe emptying runoff of some kind directly back into the canal.

I walk across the highway to the other side, lean over the same crumbling concrete guardrail and look down into the stagnant cesspool. As I slowly raise my head, I follow the canal as it extends in a straight line out to Lake Michigan. The huge, shadowy metal structures of the steel makers stand along the shore, and next to them, barely visible, a towering crane. If there are any tankers below in the port, it’s too dark to tell. But out over the lake, beyond the man-made gloom, twinkling stars remain free for those who may need to see them.

To the south and west, the sky has slowly turned from pinkish yellow to an ominous orange glow, making it appear as if there’s a giant fire somewhere in the city behind me. In the distance, I can see the lights of the Indiana Toll Road crossing through Wolf Lake. From there, this landscape and all who try to survive in it have become invisible—pipes, depots, cattails, canals, tankers, teenagers on bicycles, all a mere blur if seen at all. But from the ground, from here in the middle of the stillness of the industrial night, I can feel the rawness of the earth. Barren but not dead, this land is still alive, and in its living there’s something as real and wild as anywhere I’ve ever hiked. As I breathe, I can feel it seeping into my lungs and flesh and the ventricles of my heart. In its wildness the past is still very much alive, a reminder that nothing is forgotten or invisible. That destiny, as its Latin root “stinare” implies, comes from where one stands. And where am I standing? In some remote, industrial no man’s land far from human habitation? No, I’m standing within walking distance of where I live, work, and turn on my tap for water along with ten million other people on the shores of this Great Lake.

Far ahead, I see a stoplight, a few random streetlights, and a hint here and there of homes and buildings. Walking quickly through an unruly stand of wild sunflowers growing out of the broken sidewalk, I make it over the bridge and out of the thicket surrounding the canal. On the other side, I’m greeted by a sign erected by the Lion’s Club cheering me on into East Chicago. Incredibly, no more than a few hundred yards from the canal and the eventual storage site for its toxic sludge is not only a park with tennis courts and a par-three golf course but also East Chicago Central High School and a newly built middle school. At least two thousand students within a windy day’s reach of a toxic dump site.

On the other side of the road, pipes belonging to another of the many energy conglomerates in the area, Buckeye Pipeline, run into the darkness along the canal, reminding me just how many pipelines crisscross this whole region, transporting oil into and out of BP and other oil companies. Enbridge’s infamous Line 6A ends its cross-continental transport of thick bitumen from Alberta just a few miles away. Enbridge Line 6 Oil Pipeline is a major pipeline in the Canadian/US Enbridge Pipeline System, which carries petroleum from western Canada to eastern Canada by way of the Great Lakes states of Minnesota, Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana and Michigan. It consists of two separate lines, Line 6A and Line 6B, which end and begin in Griffith, Indiana, a few miles from Gary. The largest on-land oil spill in American history occurred in Line 6B when it ruptured in July 2010, spilling more than one million barrels into a tributary of the Kalamazoo River in Michigan.

Beside Buckeye is a fire station, which makes sense, and adjacent to it, making even more sense, is Lake County’s Mental Health Clinic. For how are people supposed to manage their sanity when they must send their kids to schools surrounded by toxic waste sites?

Thankfully, I can see more lights and an intersection near the two schools. When I get to the traffic light, a black and white East Chicago squad car pulls out of the school parking lot and slowly passes me. A welcome sign, I think, planning to flag the car down and get clear directions, but then the scowl on the white officer’s face as he peers through his window makes me realize what I probably look like: some lunatic in hiking shorts with a backpack coming out of the weeds and wasteland of BP. I put my head down as if I know where I’m going and hump it across the road toward a golden glowing Corona sign in the window of a taqueria.

Inside the taqueria four Latino men sit at a table with their bright yellow beer, chips, and salsa. Looking down the highway into the darkness of East Chicago, I wonder how far I have yet to walk to reach the casino and whether I should risk it despite not knowing really where I am. Then it begins to rain. Large drops precipitate out of the dense night air, splattering on the pavement, hitting my arms and legs, and streaking down my hot, dirty body. Another wave of fatigue hits me, and I lower myself slowly onto the concrete steps to sort out what to do: Keep walking? Flag down an errant cab? Ask the police for help? Break down and call a friend? I look back at the men through the window, enjoying their beers and fat burritos on the platters before them. Maybe they can help?

Here come the cops again. I jump up and put my cell phone to my ear in a panic, feigning my legitimacy for the police, pretending to be talking to someone on the phone. What will I say if they stop and ask me what I’m doing? Tell them I’m walking to the Indiana Dunes?

After twenty-eight miles, it’s time to let go of my pride and call a cab to ferry me the last mile or so to the casino and my hotel. So, I call the Majestic Star Casino, hoping they have a shuttle. They don’t have them but give me the number of some local cab companies. When I call the first number, a guy listens to me for a few seconds and then asks, “You’re where?” When I repeat myself, he hangs up. The second tells me it’ll take an hour and half, and the third hangs up as well.

I walk back to the stoop and slowly sit down. My hips ache, my legs buzz like they’re still walking, my feet—to the extent I can feel them—seem like bones and joints floating in a skin sack of acid, my hair lies plastered against my skull. I stink.

For a few minutes I sit there and stare into the sickly glow in the northwestern sky over the land I’ve walked through for the last fourteen hours. I take out my cheap little cell phone and scroll through the names, contemplating which friend I could call at nearly ten o’clock on a Tuesday night. But I can’t do it. It would be too awkward, too humiliating. I didn’t even tell anyone about my insane idea for fear they’d talk me out of doing it.

Then, out of the darkness, a miracle: a cab with its lights on.

I run out almost into the middle of the road to force the cab to stop. The window comes down and a round-faced Black man shakes his head emphatically and, in a familiar francophone West African accent, dashes my hopes: “No, no, not open. I’m going home.”

“But, but your light is on . . .” I plead as he shakes his head and rolls up his window. “Just to the casino?”

He speeds off.

I sit back down and decide to wait for the cops.

And they do come by, once, but in pursuit apparently of some other troubled souls. The taqueria dims its lights, and the men inside save me from any further humiliation by going out the back door. Here I sit, soaked in sweat, slumped like a sad kid on his porch stoop.

To rub it in, strangely, the same cab returns, still with its goddamn light on. Desperate, I stand up and wave him down again, thinking maybe he can call his dispatcher for me.

“I know, I know,” I start, my voice breaking into a whine as he reluctantly stops again and rolls down his window. “I know you’re going home, but I’m in trouble here, maybe you could call your dispatcher and they could possibly call someone to . . .”

“Okay, I will take you,” and he waves his hand hurriedly for me to get in.

I can’t believe I’ve heard him right, “Really? You’ll take me?”

He nods, and I pull open the heavy door, nearly falling over because I’m so tired. But I right myself and tumble into the cavernous and blissfully cool back seat, hoping he’ll not notice my near fall and think I’m drunk on his way to one of the nearby casinos. Almost immediately I begin to lie down on the wide cushioned back seat, but bolt back up knowing I haven’t yet told him where I’m going. “I’m going to the casino. I can’t thank you, really, thank you so much, you won’t believe me . . .” and I cut myself off, not wanting to jeopardize my ride. “The casino will be fine, thank you.” Relieved, he nods and hits the gas and we’re off.

“I saw you needed a ride,” he says, turning down the BBC on his radio. “I’m sorry I didn’t pick you up the first time. But I’m not allowed. Only have a license for Chicago. I thought you were maybe a set-up, maybe the police. I could get fined for picking up passengers outside of Chicago, you know?”

“No, no, no, I’m not the police,” I say, laughing to myself.

We talk a bit about his work and how hard it is to make a living for cabdrivers these days, with Uber, the rise in gas prices and endless numbers of tickets, thousands of dollars each year he tells me.

“What do you do?” he asks, turning back to me.

“I’m a writer, a kind of journalist, and I’m doing this—this experiment. You probably won’t believe me . . .” I pause and can’t help myself, seeing his curious eyes and sincere West African face. . . “I know this will sound crazy to you, but I’m walking to the Indiana Dunes. The park, the sand dunes near Gary, you know? I’ve been trying to write a book, a book about walking.”

“Where people swim—the big sand piles? Oh, yes. I’ve taken my family there once.”

“Yeah, the dunes, I’m walking there.”

“Where did you walk from?”

“Chicago.”

“Chicago? Really?”

“Yes, I know . . . Can you believe it?”

“Walking?” He muses, chuckling, meeting my eyes in his rearview mirror. “Where I come from, I think everyone could write a book about walking.”

Grinning and nodding, I lean and rest my arms on the back of the front seat. Somehow, I’m not surprised that out of the oily orange shadows of the night a West African has appeared to guide me to safety. Like a folktale, he’s arrived to remind me of those lessons I’d learned while walking in Senegal years before. All day my mind had slid into reveries of those long walks I’d taken while working in the Peace Corps. I’m not sure if it was the feeling of the sun beating down on the back of my neck or if it was the length of time and the distance that triggered the memories, but there I was, tramping off into the sandy savannahs, heading out into the sun-bleached afternoons, making my way from village to village, passing those elephantine baobab and fanlike acacia on the horizons. Again and again, memories came to me especially in the past hours as I’d made my way to the South Side where I’d arrived, heart-broken and haunted, after leaving Senegal.

In his chuckling laughter at me and my attempt to make a pilgrimage through this new home of his, I recalled the harsh realities of life in those farming villages where indeed walking was a daily routine and a necessity: the children off to schools miles away walking into the heat and swirls of dust; the women with babies strapped to their backs balancing basins of water walking back and forth from wells retrieving precious water; the Fulani herdsmen among their boney cattle; the pilgrims and the migrant workers from Mali and Guinea. Walking there, indeed, was no pastime but a way of survival.

The Senegalese farmers nicknamed me “tukkikat,” (the traveler) in the tongue of the Wolof, a moniker given to the restless, to the ones who find themselves forever on the road. They’d seen in me in a matter of months my character and stamped it on to me, with their nickname. And they were right.

In letters to me, I remember my friends and family often asked me what it was like living there in a mud-brick hut among the Wolof and Mandinka farmers and their families. I’d often say that it felt like being a character in folktale. By that I was trying to describe not only the day-to-day ways of life of rural people who lived within the rhythms of the land, where animate and inanimate were not separated, and like time itself, boundaries could not be fixed. Here, there was a sense that an act or deed mattered for all time, affecting the past as well as the future. My coming there, they’d told me, had long ago been ordained. And when I returned from walking off to another community to do my work, they thanked Allah for my return, as they did the rain and the bounty of their meager harvest of peanuts so crucial to their welfare. To them, my coming had nothing to do with me nor that of the magnanimity of America, no I was there as a sign of their belief in the powers of their ancestors and their faith in the benevolence of Allah.

I learn that my taxi-driver is from Cote d’Ivoire, and he’d immigrated a few years ago. His name is Gabriel. I’m not surprised either that he’d just moved to Indiana (Merrillville) from where else, Rogers Park, where I’d begun my journey hours before, home to many immigrants who drive taxis for a living.

As he navigates through the industrial landscape of more oil depots and empty stretches of brownfields to find the casino outside of Gary, we become so involved in a discussion about oil spills and a massive dumping scandal back home in his hometown of Abidjan that we get lost, and I must get out and ask for directions at a White Castle back in Whiting. But he cancels the meter, and after more twisting and turning through East Chicago we come upon the pitch blackness of the lake and Donald Trump’s old casino.

He’s eager to talk, having been alone all day with only his radio for company. “I drive through now every day, coming back from Chicago, looking and wondering at this, this area, these cities with the poor people and broken buildings,” he says, his hand directing my eyes to the darkened landscape before us. “I don’t understand it. This is America. How can this be? I ask myself. I didn’t think I’d find this when I came here. People living like this. I don’t understand. What happened here?”

✶✶✶✶

Michael McColly’s essays have appeared in The New York Times, the Boston Review, and The Sun Magazine. He is the author of the Lambda Literary Award–winning memoir The After-Death Room, chronicling his journey reporting on AIDS activism in Africa, Asia, and the United States.

✶

Whenever possible, we link book titles to Bookshop, an independent bookselling site. As a Bookshop affiliate, Another Chicago Magazine earns a small percentage from qualifying purchases.