Inhale. Exhale. Feel your feet on the floor.

Clothes, clothes, clothes, the clothes just keep coming in, arriving on steel racks—Z racks they’re called because the bar holding the wheels is shaped like a Z—the sturdiest racks you’ve ever seen, built specifically for the job and they just keep arriving on the big truck at nine in the morning, every morning except Monday, when the store opens, clothes, clothes, clothes, I have no idea where they’ve come from—oh, I know people donate them, but where? Here in Arizona or somewhere else and there’s so much of it, racks and racks, a never-ending cycle, in come the clothes, the guys in the rehab program (which the income from the store supports) push the racks onto the loading dock from the back of the truck, just shove them any old place and it’s now six weeks I’ve witnessed this thing and I’m still amazed by it. I stand there sorting the clothes that came in yesterday or whatever day, I’m sorting the women’s blouses, there’s more women’s tops than anything, I’ve noticed, short-sleeved, long-sleeved, separate from each other, sweaters separate including hoodies and sweatshirts, the clothes just keep coming into the back of the store at the loading dock, rack after rack and I will never catch up, I, the expert thrift-store- addict shopper, am actually sick of the stuff, sick of clothing, sick of the feel of hangers in my fingers, pulling on my semi-arthritic hands, messing with my cuticles until I remember to put gloves on and keep them on, and the racks keep coming in, every day—three or four sometimes even six or eight—every day and when the racks inside the store get stuffed full, we start “ragging out” which means pulling clothes off the store racks that were tagged before a certain date, usually eleven or twelve days prior, yesterday it was yellow tags, today it was anything older than January 15th. Some yellow, some green or blue, and if we didn’t rag out the clothes, we’d never get all the newly-arrived clothes onto the racks inside the store, so if I’m filling the racks inside the store from the racks in the back and one of the store racks is full, then I stop and rag out that rack if I want any more clothes to fit (I have to rag out that rack—Who likes to shop where the racks are so full you have to shove the clothes with all your might to even see any of them, let alone so hard you can hear the hangers breaking?).

Feel the weight of your whole body sinking down into the earth.

…. and that horrible squeaking of the metal hooks on the metal racks, I put the rag-outs into a huge red plastic rolling bin back in the loading dock, it’s so cold there I have to put on my jacket to work, and from there, I have no idea where the rag-outs go, sold by the pound, I’ve heard, and taken to Mexico, but that could be a rumor, I just don’t know; and my hands hurt and my feet hurt and yesterday evening even my back, but I know it’s because I’m in my sixties and I’m still not used to this job, standing, walking four hours a day, I’m such a wuss, I haven’t worked for thirteen years, except for taking care of my mom, and all my jobs before that were sit-down desk jobs—clerk, secretary, legal secretary—only once a waitress and I only lasted three months at that, I did not believe I could do this work for eight full hours, I knew it would ruin my body and my life or kill me! A woman younger than me had to quit the other day because of her bad hip and no health insurance to get it fixed, and I know there are millions and millions of people who do this sort of work their whole lives, maybe not in a Salvation Army store, but in Walmart and K-Mart and Target or wherever, who have to be on their feet all day, no matter what they’re doing, McDonald’s, Arby’s, Sonic, okay, now that I think about it, security guards and nurses and servers in Denny’s and Mimi’s Cafes and oh my God, department store clerks, Macy’s and Penny’s, also housecleaners—those Merry Maids—how merry can you be when you’re on your feet eight hours a day? Oh my God, I am a snob, I am a former lady of leisure, I have no compassion, I had no idea what this was like and I apparently didn’t even care.

Feel every muscle, every bone, every tendon, every ligament relaxing and letting go.

No wonder those women working at Savers (when I used to go to thrift stores but don’t anymore because I am over it, I am so over going thrifting anywhere at all in my spare time, which I don’t have any more of anyway since I’m working, except on fifty-percent-off Goodwill Saturdays, maybe, once in a while) no wonder those women working at Savers and sometimes also the young men working at Savers, they all looked so sour sometimes, and the Goodwill Girls, all rushing around putting shit on racks all fucking day long, I hope they have good shoes, I hope so, I have good shoes, very expensive good shoes that I used to hike in every day but now rush around in four miles every four-hour shift in the Salvation store (I have a pedometer), and still the balls of my feet hurt like hell after my shift—my heels, my toes, even with great shoes, my calf muscles, too—I have to take a hot bath when I get home every day and then I have to put my legs flat up against the wall while lying on my back on the floor (this thing my daughter Ariel taught me from yoga) something about the lymph system and getting it all moving again—it works, it really does!—but right now I’m thinking no wonder a lot of times you can’t find someone to ask a question of in Home Depot or Target or Walmart, they’re probably all hiding somewhere putting their feet up. They should have foot-soaking stations in all employee break rooms for all the old people who have to work because their Social Security doesn’t pay enough to live on, let alone pay for their high drug co-pays, especially when the Part D Drug Plan goes into its coverage gap phase where you have to pay full price for the fucking medication, but don’t get me started on that sad story, or that nasty-narcissistic-personality-disorder second-term president we have, whom barely half the people voted for—a lot of them working jobs just like this one I have—What were they thinking? Really. Healthcare in this country was not invented for the old or working class or poor people, although Obamacare did manage to help some of us.

Arrive into the here and now. Call in your senses. Inhale. Exhale.

A new day. This woman’s been in the store before, skinny as Twiggy, tight black jeans and a tight T-shirt, long messy brown hair, her make-up so thick it’s like a ghoulish mask. She always complains about the prices: “I could get these jeans cheaper at Walmart.”

My manager, Eric, always says: “Tell her to go to Walmart.” He mentioned once that she’s a meth addict. I wonder how he knows that. I’m an addict, I never did meth, mostly drank myself into alcoholism back in the day. Now my addictions are shopping or worrying or food, but thank God I’m in recovery.

I never notice when Twiggy comes in, she just appears out of nowhere. I’d ignore her if I could, but she seems to shapeshift; I don’t recognize her until she starts talking.

“Can I … blah blah (is how I hear it) blah blah,” Twiggy says really fast and sneaky, as if she can get her request past me without my understanding, and I’ll say yes by accident and she can hold me to it.

“I’m sorry?” I say. We’re up at the register, she’s got a full shopping cart, she’s first in line with a line of customers forming behind her. It’s fifty-percent-off everything today. The radio’s too loud, again, and my hearing—even corrected with hearing aids—is not so good.

“Can I leave these here?” She grabs four or five hangers with tank tops and camisoles out of her cart, mostly black, a couple pair of jeans. “And I’ll go just up the street and come back and I’ll get them.”

Just up the street. Circle K? Starbucks? Out to her car for a quick snort?

She means she’ll pay for some, I’ll hold some, and she’ll be back. Or not.

“Oh, you mean will I hold them for you?”

“That’s what I just said.” A bit snarky.

“I didn’t hear you.” My voice is not the most pleasant right now, either. Be friendly to customers is one of the rules. I take a breath. We have other rules. Only Christian music on the radio. Workers wear khakis and red polo shirts. Cash drawer must balance at the end of shift, even if you didn’t get a chance to count it when you started, you have to pay for the discrepancy.

I’m not told many of the rules until months into my first year.

“We don’t hold things,” I say before Twiggy can say anything else. Another rule. I’m sure she’s been told this several times before, if not hundreds before I even started working here.

She wants to leave the clothes in a cart sitting in our little store somewhere, blocking the aisle or next to the wall by the cash registers where there’s barely room for two people to move around, and who knows how long it will take for her little trip up-street, or if she’ll even come back.

I’ve started thinking the worst of people. I wasn’t always like this. Can I keep doing this job? Why did I take the first one I found? Cause Mom just died and I couldn’t think straight? And minimum wage? Surely there is something better out there.

Inhabit your awareness. Breathe and scan throughout your body.

I almost fell once because a customer plopped some huge ceramic pots right in the opening where we clerks rush behind the counter to ring people up.

“I told you I was putting them up there,” that woman said. Yes, she had told me, and my intuition elbowed me in the ribs to tell her to get a cart, but I didn’t. She said “I put them up front.” Whiny voice.

Common sense? Does anyone out there have common sense?

But back to Twiggy: “It’ll just be here for a little while,” she says, looking down at her cart.

“We don’t hold things.” What don’t you get about …

About a month ago, as Twiggy was piling pair after pair of jeans into her cart robot-like and complaining about the prices, she said, the words rushing out of her mouth. “I let friends stay with me, and they pay me back by stealing my clothes.” Some friends. Meth addict makes sense now. When I first got sober, I let a friend of my brother stay with me for a few days. He stole my oboe, five all-silver dimes off my mantel, left without saying good-bye.

The big guy next to Twiggy (I haven’t even noticed him till now) holds out a hundred dollar bill, looks at me with a dare in his eyes. This, while she’s fluttering around, messing with the hangers and the clothes in her cart, still deciding which ones she wants.

Big Guy is the third guy I’ve seen buy clothes for Twiggy. Are these dates? Like in Pretty Woman? Pure speculation. And this is not Beverly Hills. Just the Tucson foothills. A Salvation Army Family Store.

“I don’t think I can break that hundred,” I say to Big Guy. I haven’t even counted my own till yet; this is my first transaction of the day, so I don’t know what’s in there. The line’s growing behind Twiggy and Big Guy.

I’m up at the register alone, as usual. I look around, then toward the back of the store. Where’s my back-up? Taking a break? Out back smoking? There’s only two of us on each four-hour shift, not counting the loading-ramp guys or the manager. Why isn’t Eric keeping track of the store, noticing that I need help or even coming up to fill in?

Inhale. Exhale. Feel your breath move down into your lungs.

“Do you have anything smaller?” I ask Big Guy. I’m ringing up the clothes, but have no idea what the total will be yet. Not even close to a hundred, I’d bet. I wonder if it’s even a real hundred.

“Twenty-three dollars,” he says, glaring at me, pulling cash out of his wallet, waving the bills at me.

Does he want me to sell him this huge pile of clothes in Twiggy’s cart for twenty-three dollars? God!

This impatience I feel with people and their purchases! I only took this job so I could make my medical copays and pay off a credit card. My husband won’t bail me out this time.

I’ve been sober over thirty years! Haven’t I learned that wanting people to act a certain way is ridiculous? Of course they will act another way, I can’t control their behavior with my thoughts. Why can’t I just accept people the way they are?

There are now five people in line with full carts behind Twiggy and Big Guy. Backup has not appeared.

I know I’m half the problem, but how do I deal with it? I’m also half the solution, right? That’s what they say in my meetings.

I turn and look out the window for a second, across to the Catalina Mountains, pleading to God or the Universe or Somebody! Please. Help me let go of my expectations of people. Help me get through this shift without yelling.

Be aware of your breath.

I do not have to solve this myself. I always forget that. Always. At first.

I turn back to the crowd. “Just a minute, I’ll go get help.”

I walk around the counter and head for the back of the store. Stick my head in Eric’s doorway. He’s sitting at his desk, eyes on his iPhone, oblivious to what’s going on in the store.

“I need help,” I say. “Will you ring these people up? I’ll do everyone else.” He hears the frustration in my voice, jumps up, I’ll give him that, he jumps up and helps when I come running to him with my problems.

As we walk to the front, I go on a little about this woman. We’ve had these conversations before.

Well, monologues. On my part. My voice goes up in pitch, gets louder as we walk. “These people. She’s got a pile of clothes in the cart, he’s trying to pay with a hundred, what is wrong with people?” I’m almost squealing now.

“Lower your voice,” Eric says. It feels like a slap. My father used to say that whenever any of us got upset, angry, emotional. I’d watch my sister’s face to see how to act, at the dinner table, in the car, everywhere, really. Dad was the only one allowed to express anger.

“May I help you?” Eric says to Twiggy and Big Guy, in his calm late-night radio-DJ voice. He either takes the hundred-dollar bill and gives the guy change, or gives them a good deal on the cartful of clothes, I’m not sure which. They’re gone, whoosh. I wish someone would train me how to do that.

I ring up the other customers. All nice, all reasonable. All with exact change or a debit card.

Listen to your emotional and physical bodies in the here and now.

I’m up at my cash register, just finished ringing up a woman’s purchases. I turn and see a guy has dumped all his receipts out of his wallet on the other counter.

“Can I help you?”

“I’m looking for my receipt for the table and chairs I bought on Saturday.”

“My wallet looks like that all the time,” I say, all friendly. I am friendly and my wallet is always full of debit card receipts until once a week I get disgusted and go through them.

“It’s not here,” he says. He’s about my age—sixty or so, white goatee and T-shirt and shorts and flip-flops. Bright blue eyes. He has a friend with him, a tall guy, tank top, pumped-up muscles, Levi’s, probably motorcycle boots.

“I’m not sure you can get the table without your receipt.” We tell everyone to be sure to bring the proof of purchase. We emphasize it. It’s a Salvation rule.

“I just bought it Saturday.” He already said that. In a softer voice.

“You need your receipt to pick it up.” I’m still using my friendly voice, in spite of how anxious I’m starting to feel.

I am jangling inside. I look at the customer I’m ringing up, apologetic. She’s not reacting to anything.

I’m the one with the violent childhood, I am the one who used to be married to a big ex-con bruiser named Bobby who used to cross his arms across his huge chest just like that guy. I am the one who wants to run screaming out the front sliding glass door.

Oh my God. These guys are ex-cons, I just know it. Loyalty and dignity and all that right and wrong, black and white, no in between.

Wait. This is not my problem.

“Let me get my manager,” I tell him.

I walk around the counter and to the back of the store. Eric comes up and deals with Table Guy as I help other people.

The conversation escalates. Eric like a broken record saying, “I can’t give you the table without the receipt,” Table Guy saying: “Goodwill never does this to me, man, come on.” I’m concentrating on what I’m doing, so I only catch bits of the argument.

Eric is a broken record: No table without receipt. No table without receipt.

And then: “Sir, there’s no need to yell.”

Table Guy: “I’m not yelling. THIS IS YELLING! Come on, there’s a piece of paper taped to the table that has my name on it.”

Eric: “I can give you an 800-number to call. I can’t give you the table without a receipt. Salvation Army policy.”

More of the same, over and over,

Recognize that your sense of overwhelm arises as a normal response to trauma.

I’m cringing over in my corner by the door, trying to concentrate on making change for another customer. I glance over in my peripheral vision and see Table Guy’s friend—Muscle Guy—standing with his arms crossed on his chest—his big chest—and I inhale sharply.

Eric repeating to Table Guy—“You can call the 800-number; I can’t give you the stuff without a receipt.” I think the 800-number is Debra, our boss down at the main store.

“I can go get you that number.” Eric’s chipper voice.

“Why don’t you.” Table Guy’s pissed-off voice.

As Eric heads back to get the number, Table Guy says to his friend: “Goodwill doesn’t do it this way. Look at that guy, man, he’s grinning, he’s enjoying this.”

Yeah, why is Eric grinning?

Muscle Guy says: “Let him go, man, let him go.”

If I was a customer right now, I would say: I decided not to buy this. And calmly leave my cart on the floor somewhere and walk out the front door. Shaking body. Tears in my eyes. Breathless. But calm on the outside. My M.O. back in the day.

I keep wanting to say something to Table Guy but I stop myself every time. It would do nothing for the situation. I tried to talk my ex-husband down many times, it just made him angrier. And no one ever tried to talk my father down.

You are responding to old trauma. Breathe and observe. Breathe and observe.

I keep my mouth shut and keep ringing people up. I glance at Muscle Guy and Table Guy out of the side of my left eye. Glares on their faces.

I imagine Table Guy taking a few steps towards the back of the store, Muscle Guy grabbing his arm. “Let him go, bro,” says Muscle Guy. “Let him go.” Maybe Muscle Guy is in 12-step. We say that a lot. Let Go Let God a poster on the wall of the meeting rooms.

Let it go. Why can’t I do this more often.

I take a deep breath and try to ignore their conversation, let Eric take care of it and just keep doing my job—scanning items, running debit cards, taking cash, making a little conversation.

One time, Bobby was so pissed at a guy who hit my car in San Jose—careened out of an alley and crashed my rear fender—he carried a tire iron up to the guy’s apartment and threatened him so he’d pay our $100 deductible. The guy barely spoke English, was one of the Vietnamese people who escaped to America.

I wanted to escape then and I want to escape right now.

“Don’t get weird on me,” Bobby’d say, every time I cried.

I will never get over this stuff.

Take a deep breath in and out. Release your inner critic.

Table Guy and his friend have wandered off to make a phone call. Eric comes back up front in a little bit and tells me it’s okay to give the guy his stuff. The loading dock guys come into the store and take the table and chairs back to the dock for pick up.

Later, an elderly man is tottering toward the sliding glass door of the store as I walk up with a handful of hangers to put on the front rack. Tall and thin, military posture, suit pants, starched shirt and a tie.

“I like your cane,” I say as I pass.

He turns toward my voice. “I have a story to tell you about that,” he says.

I turn my head to see if anyone is waiting to check out. Nope. Don’t hang out with the customers, there’s too much to do.

The length of the cane is a pattern of rounded knobs of wood. There’s a metal piece on top that looks sort of like a king’s crown.

“It’s beautiful,” I say.

“This was my father’s cane.”

I’d love to stand and listen to him all day, I really would, I love old people’s stories, especially ones I haven’t heard before. Don’t spend too much time with any one customer. Certainly no long chats. Keep moving.

“I was born in 1930,” he says. I calculate fast in my head—he’s eighty-six or eighty-seven, eight years younger than my mom was, eleven years younger than my dad would be. Probably too young for World War II.

“My father carved this cane for himself out of mahogany. A very hard wood.” I know that because my current husband’s a carpenter.

There’s one woman standing at the counter now, looking into the front case at the jewelry. White hair. Maybe she’s listening too.

“I was a boy at the time,” the old man says. “My father carved this with his pocketknife.”

“Wow,” I say. “That’s a lot of work.” I would whistle if I could. There must be a hundred little knobs of wood on that cane.

“And he carved me one of my very own.” He holds out his hand, palm down, about two feet off the floor. “This tall.”

“Wow!” I say again. That dad must’ve loved his little boy. I feel a lump in my throat. It’s been a rough week, hell, a rough year! Mom dying. Both of my husband’s parents failing fast with their own diseases, ready to leave the earth soon.

“But that’s not the best part,” he says. His eyes shine as he looks at me. His breath smells like long-unbrushed teeth. But okay, now I’m hooked. I’m going to listen, even if people are waiting. I glance at the white-haired woman. I’ll assume she’s listening to the old man’s story, too.

“My father knew General Patton,” he says, looking at me with his eyebrows raised. “You know who …?”

“Sure. I know who Patton is.” I smile. I’m probably a teenager from his vantage point.

“My father’s family knew Patton’s family, they’d go in and out of our house.” The old man talks slowly with impeccable enunciation. An orator. I wonder what he did for a living.

“One day Patton saw my father’s cane and said ‘I really like that cane!’ Well, my father carved him one just like it, right away. Well, it took a while because he used his pocketknife.”

“Wow!” It seems to be the only thing I know how to say right now.

“And there was a traveling museum after Patton’s death, and that cane,” he lifts his own cane, his father’s cane, stand-in for Patton’s cane “was in that museum show. And now it’s in the National Museum of …” I don’t hear the rest of it. I’m getting a vibe from over by the register.

I glance over and now three people are in line, ready to check out.

“Thank you so much for telling me that story,” I tell the old man. He raises his cane in an almost salute and nods at me.

“Good-bye.” He turns and totters toward the glass door.

“Good-bye.”

I wonder if he’s driving himself around at age eighty-seven. Oracle Road might be the death of him. Lucky for me, my mom quit driving in Tucson after her first attempt, doing twenty-five mph on Craycroft, a forty-mph main road.

I wonder if anyone’s taking care of him. I wonder if all his old friends are dead, like my mom’s were in her last few years. I wonder if he’s lonely.

“I can help you at the register by the door,” I say as I walk around the corner of the counter.

“What a great story,” I say to the white-haired woman. She nods.

Stress can be seen in our reactions and it can be felt within your body.

A day or two later, a woman comes into the store with her very old, tottering mother whose long white hair is in a French braid bunched up at the back of her neck. The way my grandmother wore her hair sometimes. But I notice the daughter first.

“Mom, you can’t hold on to me all the time,” the daughter says. Loudly. Sharply. She’s got an exhausted, harassed look on her face. I remember feeling that way with my own mom.

I see now that Mom is holding onto the front wall to keep herself upright. She looks very close to falling.

I scream inside my head: My God! Get that woman a cane! Better yet—a walker!

“Here, grab the cart,” the daughter says.

Once Mom has her hands on the shopping cart, she seems OK. Steadier. Like when I used to take my mother grocery shopping. She’d use her cane or walker to get into the store, but use the cart for balance once inside.

I don’t pay much attention to Mom and her daughter while they’re shopping. I’m busy with the racks and ringing other people up.

But I notice Mom trying to push the cart into the dressing room—this is how unsure she feels about her ability to stay upright. The daughter says: “Mom, that won’t fit in there.” Practically yelling at her. Maybe her mother can’t hear well. Of course.

Why doesn’t the daughter go in there and help?

Up at the register, the daughter says “You can’t see that, Mom,” talking about the checkbook. Mean tone of voice. I want to strangle her.

Should I intervene? Salvation Army is supposed to be a Safe Place—there’s a sign on the front window—but is that only for kids or abandoned babies? I’m not sure, so I do nothing.

After they check out, the daughter leaves Mom at the front of the store while she goes to get the car. The mom stands holding on to the front wall again, as her daughter parks in front, gets out and helps her mom into the car.

Jerky movements. In a hurry, stressed, angry.

Inhale. Exhale. Do not shame or blame yourself for your reactions. Simply observe.

A few months later, I request to work the p.m. shift. It’s less busy, usually, which means less noise and less chaos. Fewer psycho meth chicks.

And I barely see Eric, let alone work with him.

I mostly work with Jay. We get along well and have a good time. He’s been sober almost five years. He came up through the Salvation Army rehab program.

We back each other up. If one of us is putting clothes on the racks or ragging out, we always pay attention to how long the line is at the cash register and come up to help. If I screw something up, he doesn’t get on my case like Eric does sometimes.

It’s almost Halloween, and the first customer is a woman yakking on her cell phone. She has bleach-blond hair piled on her head and is talking at the top of her voice.

I start ringing up her items—a witch’s costume including black hat, a couple of other things—but her conversation distracts me so much, I say: “Could you please hang up your phone? I’m having a hard time ringing you up.” Hearing loss doesn’t only mean you need more volume; it also means other noises around the area can really mess up your concentration.

She ignores me and keeps talking in a New Yorky I’m-so-fucking-smart-and-sophisticated sort of way, rolling her eyes. I glance over at her teenaged daughter whose smirk makes me think she’s been through this before and she enjoys seeing her mom look so bad and she digs seeing other people deal with it because she has to deal with it all day long.

I am so enraged at iPhone Witch’s rudeness, I screw up the ring-up. I miss one of her items before I end the sale and then I start to sign the credit card slip myself!

Inhale. Exhale. Breathe. Breathe.

My fists are clenched. But I take a deep breath and say “I’m going to get help. I’ll be right back.”

I hurry back to the loading dock, and call out to Jay who’s sitting on a crate eating his lunch. My voice is a little high-pitched.

“This woman won’t get off her cell phone and I screwed up her sale! You have to void the sale. Please fix it for me!”

Poor Jay, I do something like this to him at least once a week. He’s cool with it, thank God. He puts down his Tupperware full of spaghetti and gets up to take over with iPhone Witch, while I help the other customers.

After iPhone Witch leaves the store with Snarky Teen, Jay blows up: “That was the rudest thing I have ever seen!” I’ve never seen him this angry.

He’s at one of the racks straightening clothes and slamming hangers. He could have used stronger language, but the Salvation Army is a Christian organization and it’s a rule: Do not use profanity.

“Breathe,” I tell him.

We discuss iPhone Witch for a while, discuss how we could handle it next time—maybe say “I’ll let you finish your conversation while I ring up these other people,” and step away.

Which actually worked for me once.

Jay says “Let go of it” and we go back to work, him in the men’s clothing, ragging-out and me in the women’s, filling the racks.

That night my back and arms hurt like they haven’t in a while. I’m into the Epsom salt steaming bath as soon as I get home, even though it was ninety degrees during the day.

Breathe. Choose to move forward. Always choose to move forward.

✶

All meditation instructions are adapted from Pura Rasa: Mindfulness & Wellbeing.

✶✶✶✶

Liza Porter’s essay-in-memoir manuscript In Search of the Thickest Towel won the 2024 Faulkner-Wisdom Writing Competition. Her essays have appeared in The Write Launch, Bending Genres, Brevity, Chautauqua, Cimarron Review, Hotel Amerika, PRISM International, and Passages North. Her essay manuscript was finalist for the Cleveland State University Essay Collection competition, the Santa Fe Writers Project Literary Award, and the Faulkner Society Faulkner-Wisdom Narrative Nonfiction Book Award. Three of Porter’s essays have been noted in Best American Essays.

✶

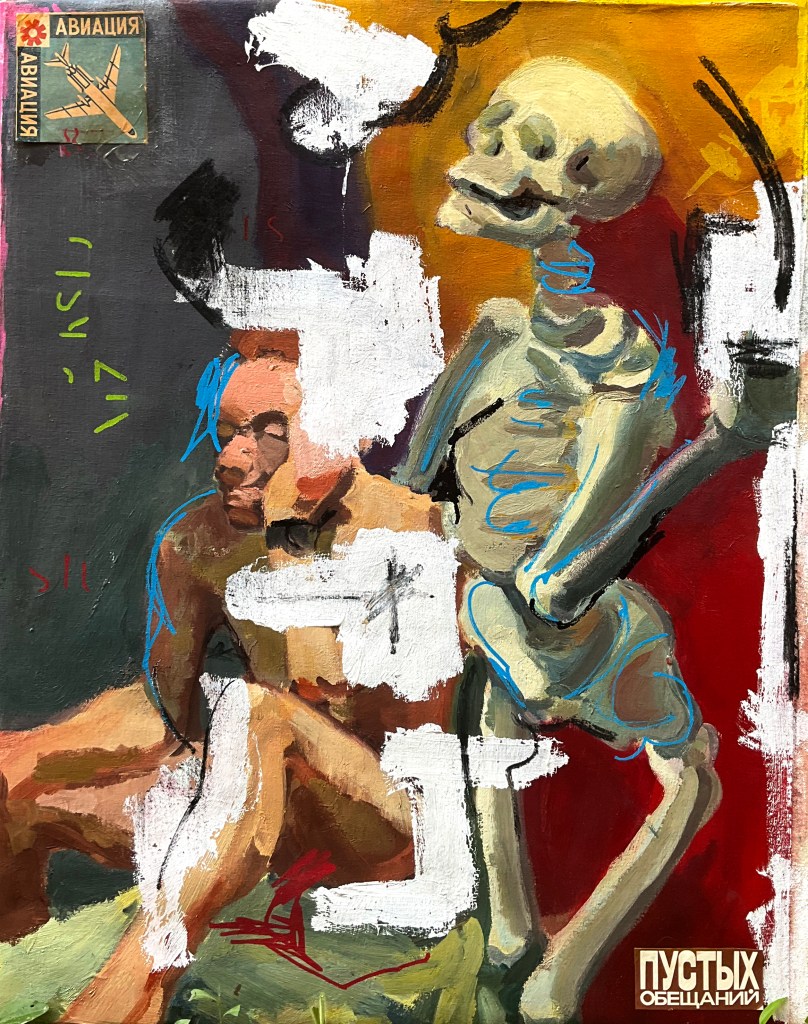

Dmitry Samarov was born in Moscow, USSR in 1970. He immigrated to the US with his family in 1978. He got in trouble in 1st grade for doodling on his Lenin Red Star pin and hasn’t stopped doodling since. He graduated with a BFA in painting and printmaking from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1993.

He drove a cab—first in Boston, then after a time, in Chicago— which led to the publication of his illustrated work memoirs Hack: Stories from a Chicago Cab (University of Chicago Press, 2011) and second cabbie book from a press not worth mentioning.

He has designed and published six books since.

He writes dog portraits and paints book reviews in Chicago, Illinois.

✶

Whenever possible, we link book titles to Bookshop, an independent bookselling site. As a Bookshop affiliate, Another Chicago Magazine earns a small percentage from qualifying purchases.