Autumn House Press, 2024, 96 pp.

Cameron Barnett’s second poetry collection, Murmur, is sharply focused and unified, comprising a wide range of forms while never losing sight of its titular conceit: exploring various types of murmurs—anatomical, astronomical, familial, societal, and historical—and how they appear as ghosts throughout his life. Over the span of fifty poems, Barnett ties the murmurs of racism to the haunting capabilities of malicious words, investigates murmurs as small as the one in his infant heart and as large as a star in the universe broadcasting a bygone world.

The collection’s second poem, “A soft, indistinct sound,” sets the tone and draws readers into the numerous meanings of “murmur.” Interspersed with standard text, italicized phrases scatter across the page, suggesting the word’s definitions as gossip, a heart abnormality, the sound of people talking—their subdued, outward expression—or a single person muttering. Barnett stretches meaning in other poems to include celestial bodies and space programs as astronomical murmurs, and hauntings as the murmured warnings of systemic racism.

Seven titular, single-stanza poems are spread throughout the collection, providing an effective narrative framework for an autobiographical speaker to introduce four ghosts—metaphors for serious events affecting his literal or poetic heart—that have left murmurs in their wake. The first poem in the series engages the medical use of the word, alluding to the speaker’s heart problems as an infant:

an echo

deep in a doctor’s ear, the sound she heard,

named it murmur—a swoosh in the space

between the beatings of my youngest heart

The heart murmur, a not-uncommon feature in children that often fixes itself, colors how his parents see him: his mother is protective, worrying he’s too active. A second ghost comes when “my father’s stethoscope / told us there was nothing there”—whether the lines indicate a previously mistaken diagnosis or the problem remitting, the murmur’s absence changes his life moving forward. In subsequent sections, the speaker describes a childhood of sports and karate, with his parents always worrying, but “I didn’t care for my heart then, I was careless.” While Barnett’s speaker may have felt like any other kid, his parents’ fears and anxieties continued to haunt his childhood.

The fifth poem entitled “Murmur” engages less with clinical problems of the heart; the third ghost materializes in his parents’ silence after hearing of his first love. Presumably due to disapproval of their son in a homosexual relationship, the speaker writes: “and my mother said nothing and my father said nothing, / and years passed with no echo to interrupt the ending.” Here, the speaker is haunted not by murmurs, but by their lack, in the form of withheld parental affection. In a sixth poem, the speaker says he is now “a haunted house of scars; and now I always fear”—both hereditary heart problems, and that “a heart is not enough to keep me alive.” The implication is that he also needs love, that less tangible murmur of the heart.

Barnett’s speaker ends the ghost motif with a final titular poem—third to last in the collection—universalizing the haunting theme:

the fourth ghost: every echo of love misplaced somewhere

deep in our hearts, reconvening over us in our stillness,

murmuring Be careful

Barnett flexes his intellectual creativity throughout, mining astronomy for metaphors about murmurs in space: that is, celestial bodies—or projects—that may have actually burned out long ago. In poems such as “Black Holes,” “Skipping Stones to Andromeda,” and “VY CMa,” the poetry and its metaphors explore communication and permanence in astronomical terms.

The speaker seems to evince a stoic philosophy in a section of “VY CMa”: “The largest star ever observed by man is thousands of times as large as our sun. This puts me in harmony with the dust.” Another section contains a diagrammed equation showing how many minutes are in a year, juxtaposed with a box containing the lines:

If time and space are one and the same

then I am the Golden Record

of Voyager 1—love with velocity

He’s referring to two identical phonograph records sent into space with the Voyager flights of 1977, containing a mix of sounds and images that show the diversity of life on Earth for possible extraterrestrial life to discover. A reader may wonder how well a portrait of the world, as seen through the eyes of a predominantly Eurocentric society in the 1970s, will have aged, should anyone ever find the audible time capsule; these are, after all, murmurs of a time gone by, hauntings in their continuing potential for communication but ultimate lack of connection.

Barnett also references the heart as a romantic symbol in this poem, representing the difference in how lifetimes are calculated on Earth versus on a star: “A lifetime is a finite thing / to waste; an eruption of the heart is a sorry thing / to miss.”

Murmur deals with artistic murmurs in a few ekphrastic poems, including “Little Africa on Fire,” which responds to the photograph of the same name taken during the 1921 Oklahoma pogrom against Black people and property. Ironically known as the “Tulsa Race Riots,” the rioters were not Black but instead the bigoted white population, who attacked Black citizens with official approval and resources. He makes clear how the event has haunted history:

There are three parts to a ghost story:

The Specter—planes in the sky,

dynamite dropped on a Black crowd,

a white mob, a machine gun expelling

bullets, American flag high behind it

The speaker can’t escape from this haunted history any more than he could escape his broken heart or a racist mob. Barnett skillfully engages murmur’s meaning as gossip and rumor while also addressing the conspicuous quieting of the event from history as taught in schools, relegating it to a ghost story—essentially a falsehood:

The Murmur—we know a lie when it unfurls

in our hands, how consequences char

irregularity into myth; we know our hauntings

because a family keeps its ghosts close; we know

pain, we know plunder, we know echoes.

As in Barnett’s debut collection, The Drowning Boy’s Guide to Water, modern-day racism and social justice themes are clear throughout this book. At times, he comes at these subjects facetiously, as in the poem “Reading Black Poems for White Audiences: A How-To Guide” (subtitled, “Part 3: The N-Word”)—evoking the murmur of a crowd, whether of interest or disapproval. The poem turns on lines that advise the reader not to be alarmed when a “well-meaning man in his 70s” says to you, “your poems are good but I’m just tired of Black / poets making me feel bad about slavery and Jim Crow.”

Barnett touches on the murmured horrors of chattel slavery and its legacy for Black Americans directly in poems like “Clotilda”:

I think: somewhere a MAGA-minded son of the south

reads about the last slave ship to bring Africans to America, jokes

about a return trip back to Benin. ‘Least we know how this ends—

say it with me: states’ rights, Southern way, Calloo-Callay, no work today.

In “Muck,” allusions are found to the legacy and continuing danger of police violence against Black Americans—a murmur that has haunted them in differing forms since they arrived on this continent as slaves:

The truth is that any two feet can be standing in the wrong place.

There is a muck none of us knows what to do with, but some of us

get to scrape it from our boots. A thin blue line is all that separates.

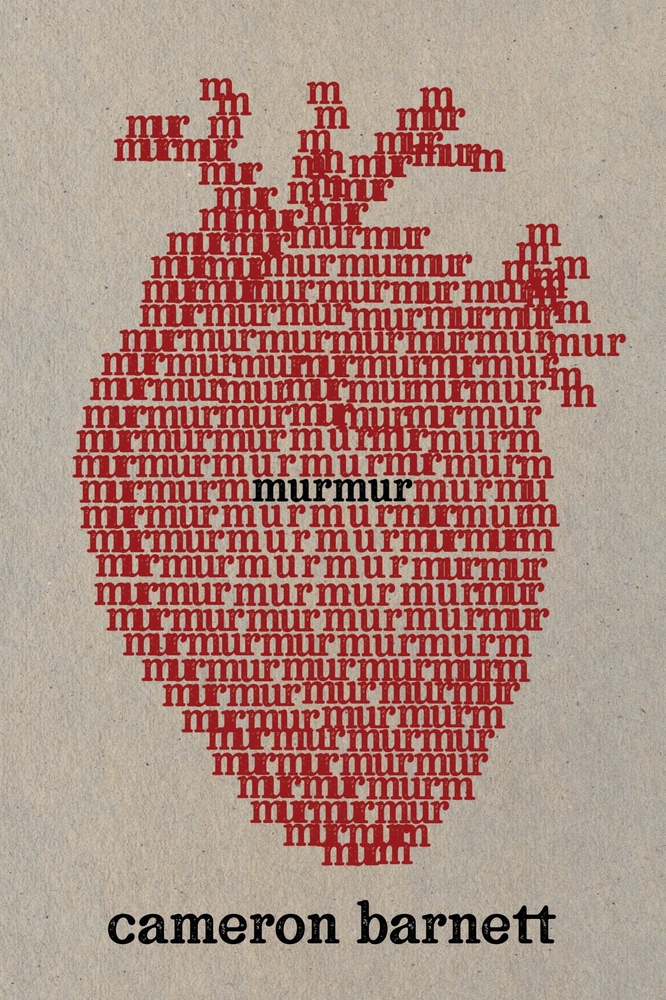

Barnett’s debut—a nominee for a 2018 NAACP Image Award—showed his talent and projected a clear voice and sense of style. Now the poet is delivering on that promise; he has plenty to say and he says plenty in Murmur. A reader might interpret the book’s cover image as representing the many murmurs taking up space in the poet’s heart. This collection shares them with candor and care.

✶✶✶✶

Aiden Hunt is a writer, editor, and literary critic based in the Philadelphia suburbs. He is the editor and creator of the Philly Poetry Chapbook Review, an online literary magazine dedicated to poetry chapbooks. His literary criticism has been published by Tupelo Quarterly, On the Seawall, and Fugue.

✶

Whenever possible, we link book titles to Bookshop, an independent bookselling site. As a Bookshop affiliate, Another Chicago Magazine earns a small percentage from qualifying purchases.