Hera Books, September 2024 (UK only)

Chapter One

Madras, India. 1974.

In St Ursula’s convent, it took hard work to make time for dreaming. Half the day was sweeping and mopping. But when the brooms were back in the cupboards, and the clanging bell signaled retreat to spiritual study, Savi climbed the narrow wooden staircase into the dome of the basilica to the warm, still air of the belfry. Below, novices drew water from the well. Mother Verity dozed in her study. The duty sister supervised the rolling of dough in the kitchens. She cast her gaze outwards, over the shining Bay of Bengal, at a world outside the sisters’ endless rules. A world of cars, trains and airplanes, instead of droning prayers and lonely echoes in stone passageways. She knew names from the dented globe but was unsure of her pronunciation – Tierra del Fuego. San Francisco. Bujumbura. Kamchatka. Surely people in these places did not have to sleep three to a bed.

In lemony afternoon light, a white-banded steam freighter puffed through fishing catamarans. A soft wake wound behind. Soon, it’d reach the new port, and she’d see the cranes hauling wares from Singapore and Penang. One day, given a chance, she would hide in the hold of a boat like that and go far away. Much closer were the fisherwomen swatting away flies as they sold heaps of mackerel along Pattinapakkam beach.

Some girls fixed their dreams and their identities. They whispered at night, ‘I want to be a film star,’ or ‘I want to live in a huge house with a big swing in the garden.’ Spoken aloud, their desires grew in impossibility. The saddest ones wished for their parents back. Few had sympathy for their childishness.

When she was knee-high and knew only her village, Savi had spent a thunderous night in a tree hollow, clutching Mekku, her chestnut goat. She’d searched past sunset for the lost kid in the boulder-studded hills encircling her village, finding her inside the tree. Thunder shook them and the ground beneath. The kid mewled and nuzzled her. She scratched the white patches behind his ears. Together, they waited for darkness to pass, and a new day to break.

Her heart sat lower in her chest when she thought of that goat. Her father had sold him in the famine’s early days. Later, he regretted it. Three meals of curried mutton are worth a hundred millet bowls, he lamented. But then again, he reminded her, she had been meatless, a walking skeleton, useful only for marrow and innards. She was my friend, she thought, wishing she could grind appa with her eyes. My only friend.

There was no way of knowing her exact age, but she couldn’t have been older than six when the drought struck, teaching her that the world offered no second chances. Appa mounted the recruiter’s truck, abandoning her and amma for two meals a day. Through the haze of kicked-up dust, he looked back at them coolly, like they were strangers. Amma bundled their belongings. His eyes had spoken. He’d never come back, never send money. The hunger-march from the village to Madras took five days but carried the timelessness of sleep. There was no land, no road. No nutrition to make memories with, no power for the brain to store images. Walking on blistered feet caused permanent damage.

They collapsed outside Santhome Basilica on Marina beach. The world had shrunk to the size of a gunny sack. Sounds were muffled; color blunted to brown. Serene figures – later, she’d learn they were nuns – moved through the encampment, offering bowls of warm chicken-stock broth. Sunlight rushed in, dissolving the fog. She marveled at the ocean’s dazzling sparkle, its rolling roar. Pain surged to her knees from the balls of her feet.

Amma didn’t open her mouth when the nun held the bowl to her lips. Her neck had no strength. The nun wiped flies off her face and moved on to another family. Savi called the nun back, insisting her mother would get up again. But amma turned away from the roaring water and closed her eyes. She lay her head on her mother’s sunken chest; her tears soaked amma’s blouse. A creeping cold spread over the world. She shivered, blanketed by the nuns, watching an open-topped truck collect her mother’s body. The municipal workers removed amma’s red-and-white bangles. Later, a nun gave them to her in a cloth bundle. They were too big for her, but at night, she wore them when she cried, wondering where they’d taken amma’s body.

Her world of fields and scrub jungle narrowed into the musty corridors of St Ursula’s. The convent was attached to the basilica like an eleventh toe, squeezed in among the outbuildings. More than five hundred orphaned girls, twice the dormitory’s capacity, made their home there. She was assigned the number 498. They slept three to a pallet, went to school, fifty to a classroom, and repeated lessons after the sisters in a sing-song voice.

The girls were forbidden to speak their local languages or pray to any former gods. If the sisters overheard them, they were beaten with switches. Tamil and English and a love of Jesus, porumaiyin sikaram, the pinnacle of patience, were drilled into them along with the knowledge that the convent could not house them long term.

The drought cast its shadow over mealtime. The girls ate in grateful contemplation their bowl of runny porridge and two slices of bread. Savi no longer starved but her hunger remained. She wasn’t as devout as the other girls, but she felt that Jesus would understand and forgive. The first time she’d seen him up on the crucifix, her stomach had contracted in sympathy for the state of his ribcage. Like her, He too must have starved. Must have seen only in grays and browns.

The basilica’s spire, in sun and shadow, kept a stern watch over them. The bay was hidden but always heard. It woke her up each morning and lulled her to sleep at night. Alone, alone, the waves sang. No Mother. No Father. Forever and always alone.

Some girls, like her, were drought-fugitives from Rayalaseema and other parts of the interior. A large contingent came from the northeast, Mizo and Assamese. Others were local and had bounced from one Catholic organization to another before turning up at St Ursula’s.

One assembly after Angelus, Mother Verity waved a newspaper. Rationing would end soon. Savi was euphoric, tummy rumbling. She imagined a feast of sambar, chutney, rice, and poppadom. She retrieved the newspaper from the pulpit. In English, it read that Americans were sending food aid to India in big ships. How rich must America be if they can fill ships with food, she thought.

Under the covers, she kept her gods, counting prayers at night in sets of three with her mother’s bangles under her pillow. The nuns didn’t know much of what went on under the covers after lights out, when girls laid sorrows bare. Her bedside partner, Ratna, had night terrors. She whispered her nightmare – her house burning to cinders, glass from the window, black collapsing beams, flaming curtains – the cries of her baby brother. They held each other’s secrets, growing up together, years passing as they memorized the hymn book and learned better how to avoid the whistling neem switch.

She counted ten Christmas midnight masses. Each year, as they marched in the candlelight procession through the courtyard, the memories of her earliest years grew faint, but one memory always came back: the walk through scrub down to the village kadamba tree beneath which the traveling puppeteers told stories by firelight.

They saw what happened with the older girls and began to understand their fate. The quickest learners were placed in households as domestic servants. The most obedient were selected for the novitiate and departed to different convents to eventually take their vows. The rest were turned out onto the streets with nothing but small bundles.

Occasionally, rich women visited. On those days, the girls missed their afternoon lessons and instead took oil baths and plaited their hair. They lined up along the wall by the well. Later, one of the older girls would be instructed to pack her things. At night, after the supervising matron began snoring, the girls argued over the ideal employer.

‘You want someone who treats you like family.’

‘Bullshit! They will treat you like the family dog.’

‘You remember Asha from two years ago. I saw her when I went with Sister Virginia to market. She was wearing such beautiful clothes. She told me that her madam gives her Sundays off and money to go to the cinema!’

‘That’s luck.’

‘It’s not luck. It’s God’s choice for you.’

‘What about you, Savi?’

‘Anything. I’m fine with anything.’ She rolled over, afraid that if spoken aloud, her desires would turn foolish.

More and more, she slipped away from her duties to gaze at the ocean. We are free, the nuns proclaimed. India is a free nation. But the wind whipped the waves far out to sea. She wanted to stand on a jutting stretch without fearing that a switch followed the rushing wind. White stone walls trapped her, but she knew even less about what waited outside.

Few girls were sure of their exact ages. She calculated that she was probably fifteen or sixteen now, not far from aging out. Where would she go on that day? Return to her village? What could she do except find a household willing to take her? She was proficient in sweeping, mopping, embroidery, cooking and washing-up. All performed in the spirit of obedience. In the mirror, she saw a skinny stranger with oversized, child-like dark eyes, and thought, who could want such a strange, sad-looking person for their home?

Mother Verity was a large Anglo-Indian woman. She could be cruel or kind depending on her mood, and she was the hardest hitter with a switch by far. Though she’d long ago noted that Savi’s chapel prayers lacked sincerity – some girls turn their backs on their village gods. You, child, will never leave yours – she still liked her, for some reason, entrusting her as she aged up with the daily ‘duties’ sheet that listed each girl’s chores. Savi monitored them, kept them on task. And yet, when the list of girls selected for the novitiate was pinned to the notice board outside the assembly hall, she wasn’t selected.

Ratna’s name was among those listed. Advanced training in Shimla awaited. Savi was pleased for her but relieved for herself. She could never take those vows of finality. How could you renounce the world if you didn’t know what you were leaving behind?

Ratna cried as she packed, admonishing Savi for not praying with more energy. ‘What will you do when you leave here?’

The dormitory was empty except for them.

‘I’m not sure,’ Savi said. A reckoning was coming, she sensed, with how little she knew. ‘But I don’t think I will be satisfied until I see what’s there.’ She pointed in the direction of the bay.

‘Overseas?’

She nodded. After so long, she’d voiced her desire. It hung there, impossible, but no more impossible than a moment before.

‘Overseas,’ Ratna repeated, awed. ‘Do you know anyone who has gone?’

She shook her head.

‘I will pray for you.’ Ratna hugged her. ‘I will pray that you get there.’

The cohort departed for Shimla, leaving Savi feeling old and useless. Days eked by. Any moment she suspected she’d be asked to gather her few things and leave. Even expecting it, she shrank when the summons came. Her tread was heavy up to Mother Verity’s study.

She waited in the anteroom for the axe to fall. This was the convent’s highest point, looking out on six small white towers and the belltower of Santhome Basilica. Beyond, the Bay of Bengal stretched into an explosion of white light.

She knocked and was granted admittance. Inside, she was startled by a woman who looked nothing like the nuns. Petite, tightly wrapped in a green sariwith dark eyeshadow and a large gold bindiin the center of her forehead, she was the first woman Savi had ever seen whose hair stopped at her chin. She leaned back in the chair, utterly relaxed.

‘Touch her feet, child,’ Mother Verity commanded in English. ‘This is Renuka Nandiyar. She’s a sariyana prominent lady. Understand? A big supporter of our cause.’

Sariyana. The real thing.

The woman smiled tightly. Savi was struck by how shiny and thick her short hair was, as though she took daily oil baths.

‘Madam, this is the girl I was telling you about. Savitri speaks excellent Tamil, and her English is respectable, you’ll find. She has a diligent spirit and never talks back – a true servant heart. She’s a good girl. You’ll see.’

‘Is your name Savitri, child?’ the Indian lady asked in Tamil.

She nodded, upright again, awed by the necklace of large jewels rolling and glinting before her.

‘And how old are you?’

‘Seventeen,’ she answered, unsure of her exact age.

‘What are those, child?’ The woman pointed to the red-and-white bangles that Savi wore. The only possessions from her now dead mother. The only thing that had survived the long walk from Rayalaseema.

‘They belonged to my mother.’

‘May I have them, child?’

The light seemed to sharpen. It lit up the woman’s large eyes, reflected off her jeweled necklace. What could such a rich woman with big jewels want with her bangles? She looked to Mother Verity for guidance but she, too, held herself apart, like an icon in an alcove, observing. Not knowing what to do, Savi began to pull off the bangles.

‘Oh, child.’ Suddenly, the woman threw her head back in laughter. ‘Look at her! How sweet! Ready to give up what little she has. What a heart she must have! Mother Verity, you are a miracle-worker! How you raise these girls?’

Savi stood still, face blank, feeling somehow pathetic. What a strange joke. What if the world was filled with such jokes? So long she’d waited for the chance to leave. It was here. It was this woman.

Mother Verity instructed her to read H. W. Longfellow’s ‘The Village Blacksmith’, a poem she’d read many times for elocution.

The book of English poetry felt heavier than usual. She struggled to focus. Was this woman to be her mistress? She crossed her legs in a way Savi had never seen before. Jewels snaked around her ankles. She looked foreign somehow.

The simple words of the poem were robbed of meaning. They came out as unfamiliar sounds. Her mind raced ahead. Perhaps the distance between India and overseas was not so large. But the distance between her life and this woman’s was even bigger.

She stopped suddenly, realizing she’d pronounced the ‘h’ in ‘honest’; how many times had Sister Virginia corrected her?

The woman bent her head, urging her to keep going. She finished the poem with no further mistakes. Her future came down to the kindness in this woman’s face.

‘Madam – this girl is one of the best. For years now, I’ve had her in mind for your house. She will meet your standards.’

The rich woman shifted in her chair. ‘Child, in my estate, we are fair. You will have your own place to sleep. You will receive ample food. You will have every second Sunday off. If you work hard, no one will raise a hand against you.’

Her voice, too, was steeped in jewels and riches.

Mother Verity spoke. ‘Now, you will have a new mother and new house. This means you have runa. You know runa? Debt. They are giving you food, shelter, salt, loving kindness. You must give them good work. Understand? You have my blessings.’

After their guest departed, the lands beyond the bay felt a thousand times further. Our world is so big, she was realizing.

Mother Verity fixed her with a look. ‘Child, from the day your mother died, I’ve watched you grow up. Understand. I’m not punishing you. I’m not making you a servant forever. That is a powerful woman. Every newspaper you’ve ever seen, it’s her husband who prints them.’

Not forever. One day, a cow stops producing and is allowed to retire. Was that the life they had in mind?

‘Be of service to that family and who knows how she will reward you. She can give you the life you want.’

She nodded, not quite as thrilled as Mother Verity. That had always been her weakness. She couldn’t take things on faith. Still, something would be different. Possibly better. She’d have her own bed, for starters. She returned to the cold, windowless staircase and wound her way to the dormitories where she’d spent most of her life with five hundred others who had nothing.

✶✶✶✶

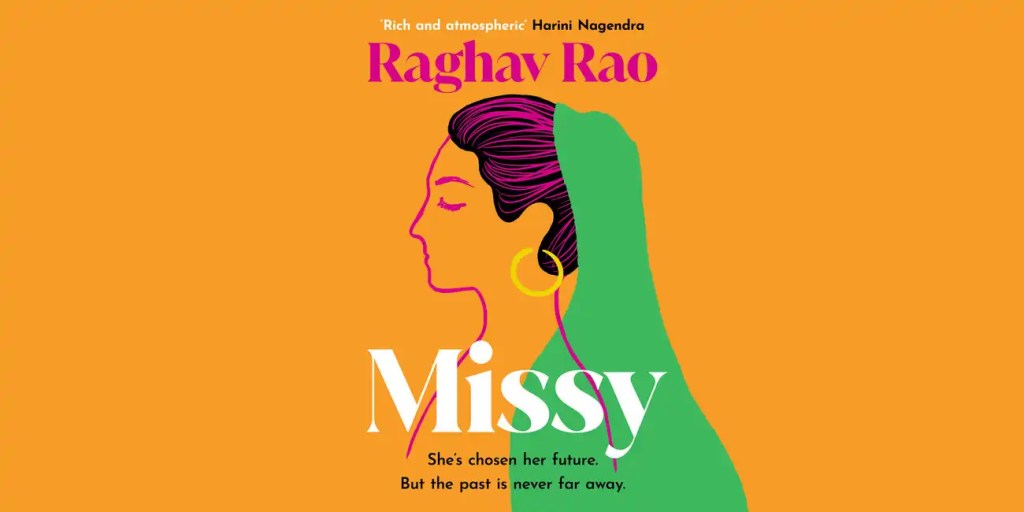

Raghav Rao was born in Mumbai, India, was educated in Southern India, and has lived in Los Angeles, London, New York, and now Chicago. He is a graduate of the University of Chicago and holds an MFA from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Rao enjoys birdwatching, playing squash, and biking the lakefront trail. Missy is his debut novel.

✶