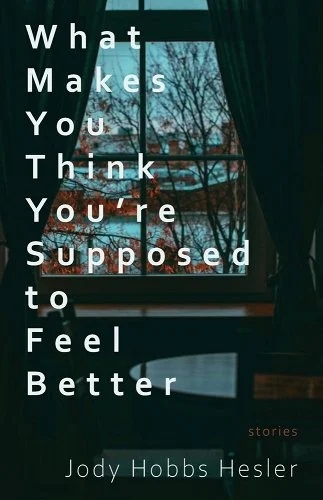

Cornerstone Press, 2023, 253 pp.

We love reminders that we’re resilient, discovering motivation we didn’t know we had, uncovering an impetus that is finally tangible and real—that makes us do something. We’re always looking for answers on how to push ourselves forward.

And yet, the driving factor that keeps us living and wanting, even through immense tragedy and devastation, remains elusive. Jody Hobbs Hesler extracts and examines this feeling in her new collection of stories, What Makes You Think You’re Supposed to Feel Better.

Hobbs Hesler disappears behind her deliberate prose, and each character embodies their primary desire: alone time, forgiveness, a do-over, attention, love from a daughter, a thank you, to be part of the family again, a baby. As they seek out solutions, taking missteps along the way, her characters each meet a moment of truth, and we get to observe their intimate thought processes to keep themselves sane, to keep them alive until tomorrow.

One of the most gutting stories in the collection is “Things Are Already Better Someplace Else,” in which an ex-husband kidnaps his daughter out of her mother’s front yard. The mother deals with judgmental policemen, assuming they think they’re too “upstanding and kind-hearted to be such a twat to their women, or their women are tougher than you and wouldn’t take that kind of shit anyway.” The second-person point of view drives the feeling of panic as she imagines the worst. The theme of that elusive driving force is present here, as she ponders the cops’ harsh judgment on her for putting up with abuse in the first place. She thinks, “Well, you don’t know what you’ll take until you survive it, do you?” You don’t know how far you’ll go.

Abuse can be unexpected, and you tend to rationalize—it couldn’t really be happening to you. In a way, it separates you from yourself, so you make excuses and pretend everything is fine, leading to a cycle you can’t escape.

A similar cycle is present in “Next to the Fortune-Teller’s House.” The narrator wants answers about her pregnancy so she can be prepared for another miscarriage—not as broken by it, maybe. Pondering giving her psychic neighbor a visit, she thinks, rather beautifully: “I wake up each morning thinking of polar bears. When it isn’t cold enough for them anymore, they will die. One day there will be a last one. Is today my baby’s last day? My body her shrinking ice cap?” Once again, the cycle; once again, lingering hope.

In “Damage,” David is recently separated from his wife and works long hours. He misses out on what happens at his former house and with his two teenage daughters, until his youngest calls him one night in an emergency. As he takes part in punishing the boys who caused a ruckus at the family home, considering whether to give them another chance, he thinks, “Who in this world gets to put things back the way they were?”

It’s in these moments that Hobbs Hesler subtly presents space for the reader to ponder the lessons we learn at any age, picking apart notions that we should get second chances.

After getting released from prison in “Sorry Enough,” Buckley decides to donate his newfound free time to working in the yard that belongs to Ida, the old woman he hit with his car while driving drunk. He thinks he’s changed enough, lost enough weight, that she won’t recognize him; he wants to commit a good deed without recognition, possibly so he can forgive himself and stay sober—efforts that end up backfiring.

After many days of his work and their interactions, Ida finally admits that she recognized Buckley from the day he knocked on her door to offer his help. She says, “When you showed up here, I knew the only person you weren’t finished harming was yourself.” He replies, “Is that supposed to make me feel better?”

“Lord, son, what on earth makes you think you’re supposed to feel better?” Ida asks.

As each of these diverse characters strives to feel better—to find forgiveness, to release their anger on a stranger so they might get some peace, to ask for one more chance—they’re confronted with contradictions: the world will never provide peace, not the type they’re looking for. But other people can offer respite, and the smallest moments bring courage, which keeps us moving.

In “Beautiful Day,” dog walker Daggett revisits his old neighborhood, chock-full of uncomfortable memories of love and loss. A woman walks by, and he expects she won’t notice him. Instead, she says, “It’s a beautiful day, isn’t it?” The simplicity of the question makes Daggett “belong to this street again, to the wide universe, so he tips his head to look up at the crisp greenness of the trees, the clouds puffing across the swimming pool blue sky, the inky purple ridge of mountains in the distance.”

A character realizing how beautiful the day is almost sounds trite. But here, Hobbs Hesler delivers relief at the right moment, when someone lost is actively looking for signs, only to find them in an unexpected connection. We have all been exactly, perfectly, there.

As George Saunders asks in his story “Tenth of December,” “Why were we made just so, to find so many things that happened every day pretty?” We continue the act of noticing, that we’ll finally be recognized for all our trying.

✶✶✶✶

Meredith Boe is the author of the chapbook What City, which won the 2018 Debut Series Chapbook Contest from Paper Nautilus, and her work has appeared in Passengers Journal, Newfound, Sad Girl Diaries, Chicago Reader, After Hours, Mud Season Review, and elsewhere. She has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and she contributes to the Chicago Review of Books.

✶

Whenever possible, we link book titles to Bookshop, an independent bookselling site. As a Bookshop affiliate, Another Chicago Magazine earns a small percentage from qualifying purchases.