The “view from my window” has become a common trope on social media. I first saw as it as a humorous Facebook post inviting me to an event hosted by Erick Cavalcanti for “sitting at home, staring out the window.” This event was “held” on March 14, though it seems to be going on indefinitely, based on the follow up comments and photos this invitation inspired.

I didn’t send a picture of the view from my window, not that it wouldn’t have been a nice picture. If I had sent in something, you would have seen the sun reflecting off the neighboring building’s windows, budding trees, or a very brightly shining Venus in the clear, western sky. The windows in our apartment in western Berlin, in the heart of the former West Berlin, also all face west. Keeping it simple. It is spring in Berlin and the view from my window is lovely.

But the main reason I don’t post anything is because the view from my window shows people. Lots of people—going shopping, walking their dogs, sitting on benches and talking—people everywhere. The “view from my window” posts only make sense in a world where inside and outside are in dramatic opposition to each other. In Berlin, though, unless you really are quarantined, there is no such tense dichotomy between inside and outside. We can go outside any time we feel like it and for just about any reason. We are not on “lock down” and never have been. Oh, sure, the state and city governments of Berlin have issued guidelines and even new rules that are enforceable by the police with 500 euro fines to back them up: no one should leave their home without a compelling reason. Few of these rules are really being enforced. Last week the restrictions were loosened further and now you can even spread out a blanket in the park and chill. The police will only bother you if you are a group and do not appear to be all living together. If this goes on for much longer, the commune might make a comeback.

Today, my wife and I rode our bikes to the nearby Grunewald forest. The hiking and biking paths were so crowded that we briefly considered returning home. Small clusters of people, living together or not, walked closely together, relaxed in fields, or sat at one of the many tiny beaches along the Havel River. It all felt normal, until the thought inevitably crossed your mind: is this spring outing going to kill someone?

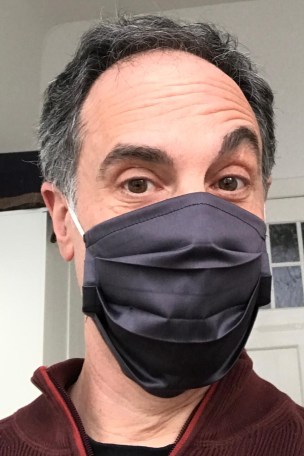

I don’t want to leave the wrong impression, though: life is not “normal.” Germans, and even stubbornly non-conformist Berliners, are mostly following the advice of their government to keep their distance from one another. Schools and universities, cultural venues, bars, and restaurants (except for to go orders) are closed. More and more people are wearing face masks. Masks don’t prevent you from catching the virus, but they do make you look frightened and frightening. But as the advice has changed and I no longer mock the people walking around with construction-grade masks from the hardware store (unless they keep pulling them down to smoke).

Now I have my own mask, a stylish fabric in navy blue, locally produced and bespoke, because, well, Berlin. I put it on when I go to the grocery store, or to the little bakery around the corner run by Ali. “Hello, my dear American!” is Ali’s usual greeting for me, in German. I respond with some lame joke about the mask, but it so thoroughly muffles my voice as to render the punchline inaudible. Ali smiles anyway, understanding that the attempt to make a joke was there, and because he is a kind person and good businessman. Ali and I usually chitchat a bit, about the weather, our families, but small talk is pointless now, not only because of this stupid mask but because only two customers are allowed at a time in the narrow shop and I feel the eyes of those waiting on the sidewalk burning into my back.

Germany has thus far escaped the worst ravages of the pandemic and has one of the lowest mortality rates. There is wide speculation about why this might be, or if it is even true; determining cause of death being one of the many things that every country seems to do differently in this pandemic. Germans generally seem healthy and hardy and, perceptually, at least, a German’s immune system can be weakened only if she sits in a drafty room or ventures outside with wet hair. We have a strong, accessible health care system. People exercise and take long vacations. None of this distinguishes us from most of our northern and western European neighbors.

Good leadership does, however. If the virus mortality rate stays as low as it seems to be, one intangible factor might be the way local and federal resources have been coordinated. We like our politicians to be bland technocrats, for obvious historical reasons, but that doesn’t mean they cannot occasionally inspire. When federal chancellor Angela Merkel goes on TV and calmly, dispassionately, asks us all to follow the restrictions, to take this seriously, and to show solidarity with each other, she is credible and reassuring. If Germans follow the rules it is not because of hackneyed clichés about the authoritarian personality: it’s because the rules seem reasonable. While food and toilet paper hoarding has subsided, some things are still in short supply, and some bastard who should rot in Hell stole protective medical gear from a pediatric cancer ward at Berlin’s Charité hospital. But that was two weeks ago.

It might be easier to be in “solidarity” here, though, because we know the State will try, at least, to take care of us and match our sacrifices. My profession, international education, has understandably been hit very hard by travel restrictions. But in Germany and most of our European locations, the blow will be cushioned. Unemployment is mitigated through a government scheme to encourage affected companies to reduce people’s hours—to as little as zero—for up to a year, with the State picking up about 2/3rds of the lost wages for most. The speed with which the fiscally conservative German government started making bailout money available has been breathtaking.

I’ve been taking calm, reasonable political leadership as more or less a given, but that’s not the case in some of our neighboring countries. After the U.S. restricted travel, our more xenophobic EU members, particularly the Eastern Europeans who never wanted to be in the EU but were forced to join or face financial catastrophe, but also, strangely, Denmark, rapidly started closing their borders. Germany only reluctantly begin to implement some closures, and now the whole EU is doing it. Reactionary measures are popular with people who think it protects them against this “foreign” virus. Food rotted in day-long traffic jams or did not get through at all, increasing the shortages of supplies in everyone’s stores. As a result, those countries needed to backtrack and loosen up the borders again.

I do worry about how long this will go on. It’s one thing to cut back for a couple of weeks, but we are long past the “snow day” feel now. As the weeks turn into months it will be harder and harder. How long will we need to teach and learn online? How long will going to have a drink with friends be irresponsible. Will there be a backlash against vulnerable minorities, as there has been historically when pandemics became plagues?

The longer this crisis lasts, the less it will matter where one lives. It’s a pandemic. We are all experiencing the same thing, only with a time lag. As if an ironic compensation for not being allowed to travel anywhere, COVID-19 threatens to make everywhere the same.

–April 19, 2020

✶✶✶✶

Cary Nathenson is a Chicagoan (West Rogers Park) now living and working in Berlin. He is an international education administrator who previously worked at the University of Chicago and Northwestern University. Cary misses baseball terribly, as do we all right now.