“Prime” can mean of first importance, at the moment of best vigor, the first hour of the canonical day in the medieval church or a number divisible only by itself and by one.

The title poem of this collection is in the voice of Willem de Kooning’s subject in Woman I, 1952. DiMaggio has chosen this word “prime” carefully for the title and title poem. She speaks variously, as all women, and then again just from her one woman’s life.

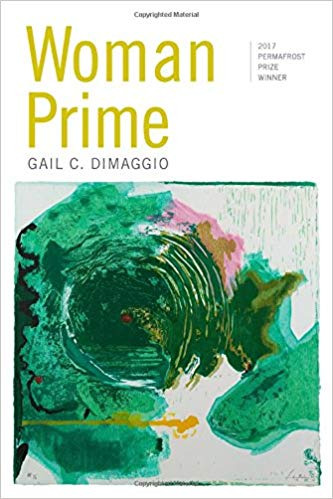

The Helen Frankenthaler painting on the cover, Radius, draws the eye inward, from the edges into a green vortex, with a small red disc marking its center. Correspondingly, about half-way into this collection of 49 poems, DiMaggio’s Radius II (noted at the bottom of the page, “After Helen Frankenthaler’s Radius 1993”) begins: “Whatever she expects, the road ends here.”

Whatever you might expect from this title or image, DiMaggio’s collection delivers a splendid more-ness – more sorrow and blood, more cutting edges and pain, more formal variety, more mothers and daughters and life than you might have thought possible in only 52 pages of poems.

The collection offers a variety of forms, cascades of couplets or tercets, short and long, in distinctive ekphrastic poems – announced as a response to a piece of art, referenced at the bottom of the poem – and in prose poems. The artists she refers to in the 13 poems are as distant in time as Mary Cassatt and John Singer Sargent and as recent as Alice Neel’s Self Portrait at age 80, from 1980, and Helen Frankenthaler’s Madame Butterfly, 2000, and Danielle Deulen’s poem “Interrogation,” 2015.

The experience of reading an ekphrastic poem differs for each reader, depending upon her familiarity with the image. By including so many here, DiMaggio takes a chance that a reader may step away from the printed page. That, of course, has always been a poet’s quandary – does an allusion or comparison stop the momentum of the read, or deepen it? If the image is familiar, as Sargent’s On the Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, 1882 or Cassatt’s In the Loge happen to be for me, there are no intermediating clicks, at least on a first read. When there is a delay – I really did not know Alice Neel at all – readers may temporarily check out. As gradually becomes obvious, the poems are also about the life of DiMaggio. We move from her childhood, with a violent father and a too-accommodating mother, through her loves, her marriage, her daughter, and beyond. We see the past, we make from words a past, we read our own pasts and presents, our own children, into all the poems.

DiMaggio’s collection is infused with Neel. She begins the collection with “Defiance in Girls” (noted “After Alice Neel, Isabetta, 1935”). Her last ekphrastic poem, almost at the collection’s end, is “Old and Naked” (“After Alice Neel, Self-Portrait at age 80, 1980”). I plunged outward and discovered the mass of glittering and contradictory “facts” of Neel’s life. Was she a grieving mother her entire life, because Ernesto, her first husband, took their daughter Isabetta back to Cuba, left the child with his parents and departed for Paris, to the artistic life Alice had thought they were planning together? Is this the same Alice Neel who wrote, according to Phoebe Hoban’s Alice Neel: The Art of Not Sitting Pretty (2010), soon after Isabetta’s birth, “When people would mewl over little kids, I just wanted to paint them”?

The very canvas of Isabetta’s portrait is a marker for the conflicts of Neel’s life, highly charged for anyone trying to understand Alice Neel. She paints it first in 1934, when she was seeing her daughter for the first time in almost three years. Isabetta is four. In the winter of 1934, that canvas was slashed by her angry lover Kenneth Doolittle, who destroyed over 60 of her paintings and hundreds of watercolors. As Neel or others tell the backstory, details become fuzzy but there’s no denying that he destroyed the majority of the work she had spent 15 years making.) What an emblem of all the oppositional force facing her as a woman artist.

In 1935, she paints the image again. The 1935 version is not painted from life but from memory. Why the strangeness of the image, the expressionistic splaying of the feet, the lines that seems to suggest breasts are already being defined (clearly not a realistic portrait of a four-year-old, even when done from memory) and the dark outlines of the genital cleft, emphasized so that the pubic region and her face are the two dominant areas of the painting?

Isabetta, whose life was also unhappy, was reported to have said that this painting pained her lifelong. In this painting we are looking at Neel the artist, a woman struggling and conflicted about her motherhood, committed to being, as Hoban has characterized her, even earlier than this period, “an anti-Cassatt.” I found myself agreeing with Hoban when she labels this painting a “shocking reponse.” DiMaggio leads us here, I suggest, because Neel is an artist, and a mother looking at a daughter.

✶✶✶

But the poems are also about DiMaggio’s life We move from her childhood growing up with a violent father and a too-accommodating mother, through her loves, her marriage, to the birth and life of her daughter, and beyond. We see the past, we read our own pasts and presents, our own children, into all the poems.

The poems. I always came back to the poems. As we proceed on through the many poems in which DiMaggio explores her own relationship with a difficult daughter, lost or leaving, running away or “driven into her own wilderness,“ what we now carry away from this art is not any answer about Alice Neel but a deep recognition that being an artist and a mother is never easy, just as being a daughter and mother is never easy. Dimaggio never settled for getting used to the pain. She surfaces it, thrusts it toward us. We feel the jagged, cutting objects glinting in so many poems – from an early wishbone “gnawed on/ “broken off and sharp” — to poems about “the Graveley,” which a reader can discover is a formidable hunting knife, what most of us might call a Bowie knife.

“Pretty as a picture” is a cliché about females that DiMaggio takes apart, whether the works are realistic or abstract. In “Empty Room/ With Mother/ and Daughter,” DiMaggio sets a scene: the child is screaming with an earache and the child’s mother seeks advice. “When I told my mother / I didn’t know what to do to soothe the pain,/ she said: Get used to it.” (There’s Alice Neel again; the poem is “After Alice Neel, Ginny and Elizabeth, 1976.)

Another formal category consists of the prose poems that often define a term: “Night,” “Soon Now,” “Light, “ “Night Train,” and ”Lightning.” “Soon Now,” my favorite, is based on a dictionary format, with meanings, which leads us as far as Kant. Then the prose breaks out of the dry dictionary talk, to the present: “But never this jubilant soon, never this brilliant now.” For DiMaggio, there’s no time standing still, no perfection insured forever and always. In the poem just across the page from “Now Soon,” entitled “We / Are/ Always/ Falling/ Forward,” she shows us that time can’t stand still. She is remembering one hot July afternoon from her daughter’s childhood, when Billy Franco is just a kid across the street and not the dangerous companion of her daughter’s later years, when “someday Lisa will follow the wrong man south,“ but all of this is impossible to see in that July without seeing the later moments because time, like her mother’s olive oil generously poured out, is always flowing forward.

✶✶✶

This review risks committing the major sin of movie trailers, giving away all the good bits. Just a few more specific poems to recommend. If you want to watch a writer have fun with the gap between titles and all that they can mean but not the tiny, narrow thing the reader expected, check out “Foundation.” And for a poem that seems a glimpse at a later writer, one with memories of so many sorrows, so many judgements but now past thinking only about bruises and blood, read “We / Argued / About / Saints.” I could not resist a poem that begins “I said: I’d sooner drink turpentine, / than sit through Sunday Mass…”

And then there’s Alice Neel, again, as the collection concludes — “After her Self-Portrait at age 80, 1980.” Before you start to read, find an image of this painting. It hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, directly across from Neel’s lively portrait of Linus Pauling (fully clothed). I travelled there from Chicago to see, in person, the startling nude self-portrait. As I sat on a bench in front of the painting, I could see Michael Jackson to my left and, just a bit further down the wall to my right a fully clothed, slightly smirky, jewel-encrusted Ann Landers. Here’s DiMaggio seeing the self-portrait:

“She’s got one swollen ankle cocked, / like a petulant child made to pose / and pose. But who makes Alice? / Only Alice… / Now, her body dissolving, she’ll do what she’s always done– / see what no one wants to see. Paint it. / Leave it behind”

This is not a book of poems one gets through, some obligatory trek through 2017 prize winners. This is a book that becomes a garden, where one wants to return again and again. Because she would need it for checking references, I returned the review copy to my editor. Then I bought the book.

✶✶✶✶

Mary Harris Russell wrote previously about Ursula K. Le Guin for ACM.