This week, ACM is posting book reviews every weekday. This is the first.

Sonnets for a Missing Key by Percival Everett

Was Percival Everett’s new collection of poems overshadowed by the publication of his latest novel, James? A brilliant reimagining of Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn told from the enslaved Jim’s point of view, James was released in March 2024, and it won him the National Book Award for Fiction, the Kirkus Prize, and a spot on the shortlist for the Booker Prize. This attention makes the August release of Sonnets for a Missing Key seem anticlimactic; however, the collection stands by itself as another work of his genius.

Everett has been called “American literature’s philosopher-king” and our culture’s “sharpest satirist.” He has written nearly thirty books since 1983, but wide recognition did not come for him until he published Erasure in 2001—the novel that inspired Academy Award-winning film American Fiction. The writer is also an accomplished abstract painter; throughout his career, he has worked as a horse trainer, a tracker, a cowboy, and a jazz guitarist. He considers jazz to be a very special musical language—an expression of Black life, refusing to be decoded and conveying messages that oral and written language cannot carry.

Sonnets for a Missing Key is split into two parts: “Sonnets” and “Other Modes.” His sonnets, each titled with musical key signatures, improvise on the fourteen-line form. Everett divides the lines into three sections: the first two consist of a single four-line stanza, and the last one is made up of two three-line stanzas. He has taken the form and made it his own with unusual breaks, an ironic voice, and subtle, cleverly concealed rhymes. The poems in “Other Modes” are titled with tempo markings in addition to key signatures. Here, Everett invents a poetic form, perhaps one that could be named a “mode,” consisting of twelve lines divided into six couplets. These modes are brief flashes of insight into a world of abbreviated, staccato imagery, the relationship between humans and nature, and the compassion the poet feels for unrequited love.

Everett has described himself as “pathologically ironic,” and his poems exhibit his virtuosic sense of improvisation with imagery, irony, and humor. The reader of Sonnets for a Missing Key will be astonished at Everett’s poetic technique, his skill, the perfection of his harmonic riffing, the sincerity of his tone, and the grace the poet employs to share with us his world.

Instructions for The Lovers by Dawn Lundy Martin

Dawn Lundy Martin has blended a rigorous academic career with an output of outstanding poetry, as exemplified in her new collection, Instructions for The Lovers. Her poetic field is dense with thought, image, and sound in poems about aging, attachments, and the fragility of life. In these verses, she reflects on her relationship with her mother, her own queerness as a lesbian experimenting with sex, and the racist conditions encountered and overcome within the American academic system.

Martin has made a stellar reputation as an academic innovator: She was the first person to hold the Toi Derricotte Endowed Chair in English at the University of Pittsburgh, where she co-founded and directed the Center for African American Poetry and Poetics. She has acknowledged the influence of Derricotte as her mentor, and several of the poems included in this volume were first published in their chapbook collaboration, A Bruise is a Figure of Remembrance, released by Slapering Hol Press in 2020.

In Instructions for The Lovers, the tension between language as a tractable, yielding construct and its physical expressions in writing and speech form the center of the poems—logical, yet fraught with emotion. The opening lines of the book are spread over several pages: words forming one or two short verses, set in the center of blank pages, with caesuras interrupting each line. These fragmented utterances seem to represent the poet’s attempt at finding the right words while mimicking childlike speech. Yet, later in the collection, her words take on sudden continuity in the titular poem:

The entanglement of loverness meant that when the

world disappeared, we could not feel our subjugation.

Cradled by the beloved. Enveloped, however temporar-

ily, in the confines of bloom, the consumption of the

ego. We swagger forth into our gendered selves along-

side American rivers.

Martin’s poetry is philosophical and has been compared to the lyric of the French Symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé. Among his themes—one also taken up by Martin—is the poet’s longing to turn his back on the harsh world of reality, to seek refuge in the world of ideas. Martin attempts, as does Mallarmé, to give poetic form to an immaterial world. Language, in these poems, becomes the poet’s medium through which she explores desire, love, grief, fear, and the tenuous vulnerability of the human condition.

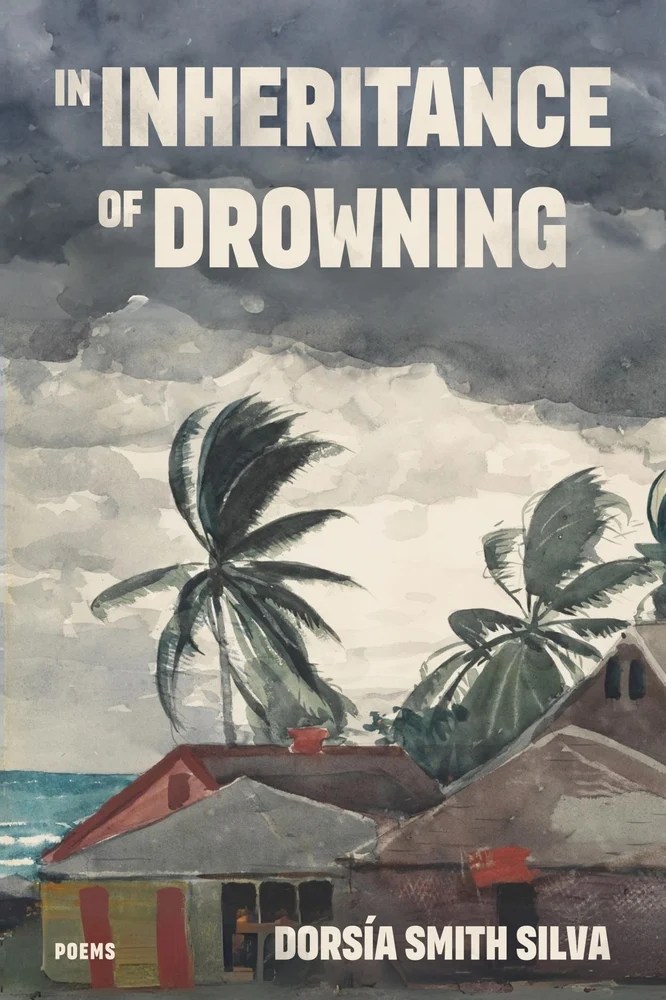

In Inheritance of Drowning by Dorsía Smith Silva

CavanKerry Press, 2024, 87 pp.

In this dramatic and poignant series of poems, In Inheritance of Drowning, Dorsía Smith Silva writes about Hurricane Irma, the Category 5 storm that struck Puerto Rico on September 6, 2017. Two weeks later, Hurricane María wreaked massive destruction on the island’s power grid, homes, buildings, and vegetation, and was responsible for thousands of deaths.

The subject of Silva’s poems becomes those “intoxicating possibilities and mysteries” that accompanied the wake of the hurricanes and the tragic aftermath. We find through Silva’s work a record of the historically circular movement of the Caribbean people as they have migrated to and from their native countries. And it is this cycle of migration which forms the structure of her collection—beginning on the island of Puerto Rico, traveling to the mainland, and then returning to the island where all has been transformed by disaster.

Her poetry also paints with a chiaroscuro effect, contrasting the landscape of the island before and after the hurricane, as in her poem, “Antes/Después Huracán María,” in which the survivors learn to live “[b]eneath a Cielo where we the watchers / learn how to become fluent / in prayer / all by ourselves.” The poetic transition from before to the aftermath of the storm affords the poet an opportunity to shift her focus from the natural disaster to the man-made disaster of neocolonial rule on the island—specifically, the institution of “disaster capitalism,” a system that enforces racism, patriarchy, and exploitation, keeping survivors in “a prolonged state of drowning.”

Silva attempts to envision a hopeful future for the survivors. In the second half of her collection, she calls for the reinvention of hope, rebirth, and renewal through the “unraveling” of coloniality. For those who were impacted by Hurricane María firsthand, and for the displaced Diasporicans who will return to their land, she writes with sensitivity and compassion.

Glitter Road by January Gill O’Neil

CavanKerry Press, 2024, 96 pp.

The poems of Glitter Road are carefully constructed from the fabric of memory, adventure, and experience. Many of these poems were conceived and penned in the environs of Oxford, Mississippi, where January Gill O’Neil was the 2019-2020 John and Renée Grisham Writer-in-Residence at the University of Mississippi.

The volume opens with an epigraph quoting Toi Derricotte, the co-founder of Cave Canem, an organization dedicated to the future of African American poetry: “Joy is an act of resistance.” We learn through these poems of the sheer joy of Black woman creativity, as well as the power of women speaking out against injustice and evil. In the poem “Narcissi in January,” the poet celebrates the feeling of being alive in mid-winter while extolling her own name:

Hard to love.

Two-faced, the coldest month of the year.

January, the first narcissi are breaking

the surface. Green spring stalks bob

their bright white heads, sway in the air—

my name attached to each one.

The possibility of poetry as protest also circulates through this work, in poems such as “No Joke” and “Driving Through Mississippi After the Capitol Hill Riot.” The South O’Neil portrays is a South clinging to its questionable history. In the prose poem, “On Hearing Mississippi’s Governor Declare April ‘Confederate Heritage Month,’” she writes: “If you say, ‘this, too, shall pass,’ then you don’t understand trauma, how it seeps into a landscape, where every inch of land has been touched by enslaved hands. I think of a war that’s far from civil in a state overcrowded with Old South statues.”

Yet O’Neil still revels in her speaker’s love of the land and the beauty of the Southern landscape in “The River Remembers:” “Here’s the nadir of our suffering, / which started in one place to end in another. / Here’s where flow and marvel and history converge. / This harm joy. This beautiful sadness.”

The notion that a woman’s consciousness can transcend cruelty and embrace love pervades this work; Glitter Road also explores the failure of her marriage, solitude, and rejuvenation through a new intimate relationship. These are poems of the dark, the light, the strange, and the familiar.

✶✶✶✶

Beth Brown Preston is a poet and novelist with two collections of poetry from the Broadside Lotus Press and two chapbooks of poetry, including OXYGEN II (Moonstone Press, 2022). She is a graduate of Bryn Mawr College and the MFA writing program of Goddard College. She has been a CBS Fellow in Writing at the University of Pennsylvania and a Bread Loaf Scholar. She is at work on two new poetry collections, a collection of short fiction, and a memoir. Her work has appeared and is forthcoming in Callaloo, Calyx, Cave Wall, Euphony Journal, Hiram Poetry Review, Seneca Review, World Literature Today, and many other literary and scholarly journals.

✶

Whenever possible, we link book titles to Bookshop, an independent bookselling site. As a Bookshop affiliate, Another Chicago Magazine earns a small percentage from qualifying purchases.