© Koos Breukel

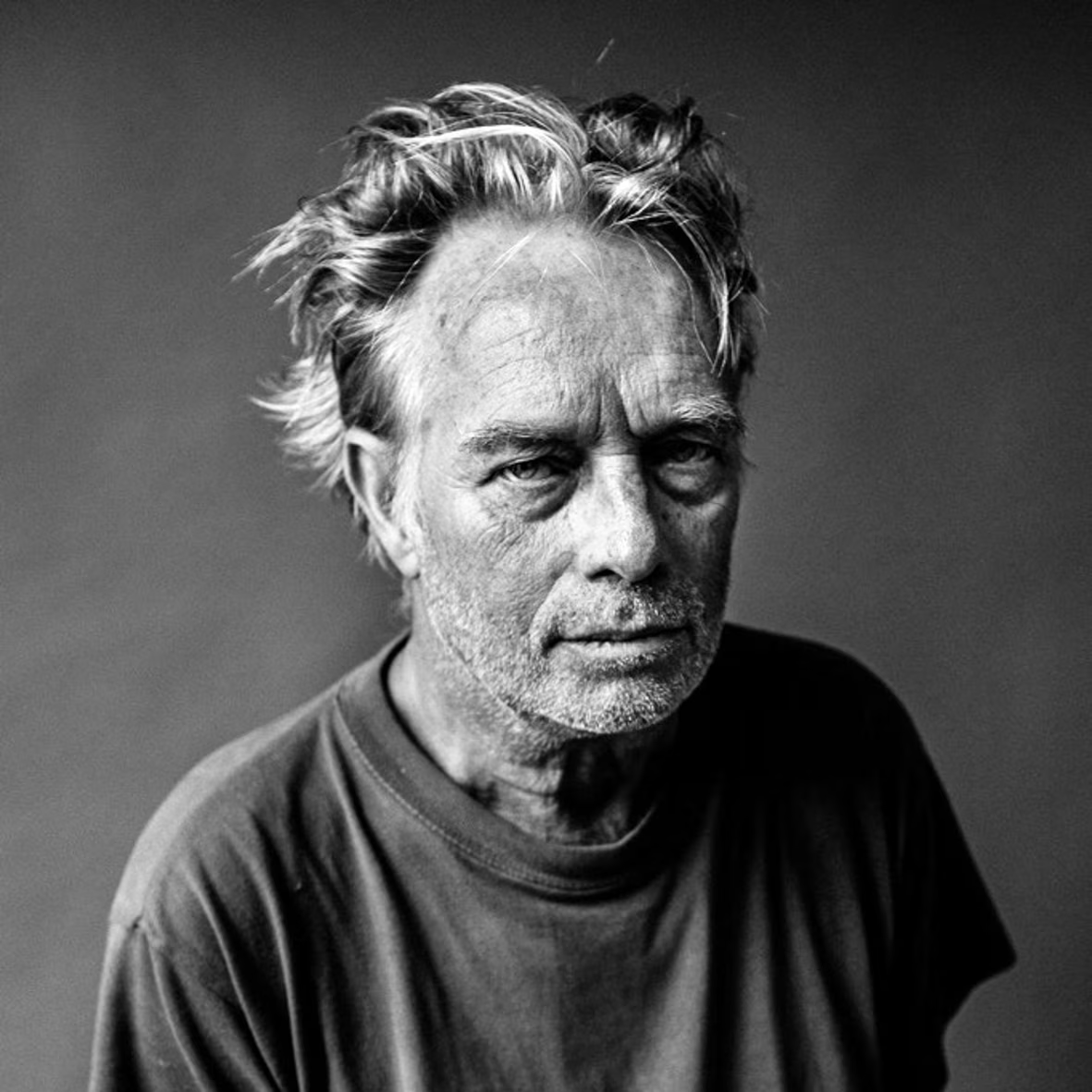

During a guest lecture at my documentary photography program in 2004, Koos Breukel took my portrait to demonstrate the uncomfortably long shutter speed of a vintage camera. I never saw the result and forgot about the picture.

Ten years later, it was part of a large retrospective exhibition of Breukel’s work at the Fotomuseum Den Haag.

The exhibition, called Me We – The Circle of Life, showed a wide selection of Breukel’s portraits. Birth, life, illness, and death are important themes in his work.

I was living in The Hague at the time and went to have a look. My portrait hung with several others, some famous, some less so. I was too embarrassed to stare at it for long, because the museum was busy. But it was a beautiful portrait and exhibition.

A book was made of the Me We exhibition, and later a website containing all the photos from the exhibition. On the site and in the museum I’m called “Student Sint-Joost,” after the name of my post-master’s program, but if you download the picture, you’ll see that the file is called “StudentScar.”

Because of the file’s title all I could see was that scar— rather than my messy hair, my freckles, everything I like and don’t like about myself.

I’ve never thought of myself as someone with a scar, but in this portrait, the damage from a dog bite is clearly visible next to my nose. A dent, a scratch, and a bump, a kind of trinity.

That file name affected me. I had graduated from art school and was working as an artist, so I knew that you label files, portraits especially, to help you remember their subjects. Old man with stern look. Child with runny nose. I laughed a little, because Breukel had clearly forgotten to change the file name to the official title. It also made me sad. I’m in my twenties in the picture and my only scars are on the surface, visible to the naked eye.

That’s different now.

Seven years after the photo was taken, I developed health problems. Very specific problems. Suddenly, I was very tired. A fatigue unlike anything I’d felt before. A fatigue as if I were seriously ill. Then my left side started tingling. From my left big toe to the top left of my head. As if a line had been drawn right down the middle of my body.

“Does it feel weird?” my then boyfriend once asked during sex.

“Only on the left,” I answered.

To my doctor, my symptoms were suspicious. They could be something neurological.

“It’s unlikely,” he said. “But we’ll have to perform an MRI to rule it out.”

The World Cup was on and people who had scheduled appointments at the MRI office ahead of me had clearly known the playing schedule. A soccer fan myself, I stupidly hadn’t looked past the group match stage, so right after the game between the Netherlands and Slovakia kicked off, I was fitted with a kind of helmet with optical illusion mirrors to prevent claustrophobia, and placed under a thick blanket because it could get cold in there—ready to slide into an MRI machine for a brain and spinal cord scan. Meanwhile, my friends were at a crowded pub drinking beer with their cheeks painted orange.

A friend with MRI experience had suggested that I ask to hear the game on my headphones. Somehow, the medical staff found a sportscaster who was able to report the soccer match intelligibly, even through the noise of the MRI. While the machine was blasting away at my brain, I lay there listening to a 2-1 victory over Slovakia. The world didn’t pass me by completely.

I was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. For me, there is a life before and after that soccer match. Koos Breukel’s portrait is from the before.

I have often considered making art about this. Not just about the MRI, but about illness and the accompanying discomforts. But I didn’t know how and, well, I suffered from an illness with quite a few accompanying discomforts. I stopped making art altogether.

© Koos Breukel

There’s a Koos Breukel photo that shows a naked, emaciated man. I had thought of this photo when, after my diagnosis, I wanted to know how other artists had dealt with death and physical decline in their work. The man in Breukel’s photo is minimally lit in black and white. His dried-out, cracked skin is clearly visible. His eyes are closed and his head is turned upwards.

The man in the picture is theater-maker, choreographer, performer, and writer Michael Matthews, and he is dying. He has AIDS and makes no secret of it. The photo dates from 1995 and is part of a series in which the sick, emaciated body of this man is extensively shown. The photos are collected in a book entitled Hyde, after Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, in which Hyde is the evil alter ego of the respectable Dr. Jekyll. Matthews’ Mr. Hyde was the monster inside him.

Breukel’s earlier work is generally quite documentary and raw. The Matthews pictures are certainly raw, but they are also quite theatrical and staged.

Matthews had approached Breukel with the request to portray his body. He saw these pictures as his very last performance.

The fact that Matthews shares so unashamedly every bit of his cracked skin and all the protruding bones that appear to nearly break through his flaky skin, makes me curious about this man. Something I rarely experience with a portrait.

Matthews died in 1996, not long after this picture was taken. He was only thirty-seven.

He has a short Wikipedia page and I’m able to find a few old reviews. Matthews was a Cuban American who moved to the Netherlands in 1984 to join his partner. The reviews are mainly of his last play, Hyde, which he completed and performed just before his death. Hyde is the conclusion of his monster trilogy, which also includes Frank (Frankenstein) and Dracula: three monsters from literature.

An online search yields many positive reviews of Hyde, along with charges of exhibitionism and emotional blackmail. His body was seen as a provocation. Sickness and dying are uncomfortable topics, HIV and AIDS even more so. Certainly this was the case in the eighties and nineties. My sex education in the early nineties consisted of a stern warning about AIDS, and when I went on holiday alone for the first time, my mother gave me two boxes of condoms. Sex meant danger. Dying, especially of AIDS, was something you did quietly and alone. But this man did not go along with that.

At the start of Hyde, Matthews is on stage with his pants around his knees. Alone and withdrawn. He does not seem to notice the audience. This was not like Matthews’ previous performances, according to the reviews. He usually managed to win over the audience at once with his charm and liveliness. Onstage, he gets dressed slowly and with difficulty–the virus is waging a war of attrition.

The telephone rings. Threatening and shrill. The outside world. But the phone is all the way on the other side of the stage and this man is not going to make it there.

A heartbreaking image. So vulnerable and alone. That ultimate exhaustion, cut off from all contact.

“I’m not a monster, I AM JUST…tired,” Matthews said earlier in Frank.

The pictures in Breukel’s Hyde are intense, not immediately pleasing, although maybe they are. The stark lighting and black-and-white aesthetic make Matthews’ appearance both shocking and vulnerable. In one of the last images, Matthews sits with his emaciated back to the viewer.

He looks around at the camera.

I found a review in a Dutch newspaper from 1996 of one of Matthews’ last roles apart from those in his own plays. He played God in Klaagliederen (The Book of Lamentations), director Gerardjan Rijnders’ adaptation of Jeremiah’s lament for the destruction of Jerusalem.

“The last image of that performance, God strolling across the stage, looking back one more time (with a grim smile, with a twinkle) is one of the most beautiful of the past season,” the review says.

Maybe it was the same look.

And then.

Then you’re gone.

“Then you’re totally dead, all day,” as my son used to say.

Maybe it’ll happen, my artwork about being ill, the experience of being inside the MRI, missing out on the soccer match, a dividing line in my life. I’ll just assume I have all the time in the world, that my body will not fail on me anytime soon.

Why would you make art about your illness anyway? Because anything can spark the urge to make art.

Sophie Calle made art because she wanted to impress her father. One of my teachers wrote to win back her husband, another to seduce her teacher into a friendship.

Three times a week I empty a pre-filled syringe into the growing roll of fat around my waist. Just as the illness itself seems like something intangible in my body, so is the drug. In Dutch there is a word sluimeren, which means both to slumber and something more sinister – to simmer.

MS can attack at any moment. The injections are supposed to prevent things from getting worse, but what exactly is worse is unclear. What the shot does, which is immediately noticeable, is leave lumps and scars on my stomach.

“Oh Ine, it’s all that aspartame!” was my friend’s first reaction when I told her I had MS.

Another one went silent.

“Well, I could also get hit by a car at any moment,” I was told a few times. Shit, I thought afterwards, I could also get hit by a car at any moment.

All this made me decide pretty quickly not to tell too many people that I was sick.

A pleasantly odd work of art about prejudice is Love Is a Strange Thing by Tracey Emin.

This video shows Emin in a bright dress walking towards a bridge in a park. On the bridge, a huge macho bullmastiff is looking at her. Superimposed on images of Emin crossing the bridge are images of the dog. Her voice-over reflects on the conversation she is having with the dog.

He speaks to her as she walks past. “Alright, Trace. How about it then?”

Of course, she is surprised. “What? Weird, a dog talking to me!”

“Well, do you fancy a fuck?” the dog asks her.

She has objections, and the dog asks her what’s wrong. Does she not find him attractive; does she not find him handsome?

Well, you’re a dog, Emin offers as her biggest objection.

As Emin walks away, the dog looks at her sadly. “He looked hurt,” she says in the voice-over. “Wounded.”

“Tracey, Tracey you of all people,” the dog says as she walks away. “I never expected you to be prejudiced.”

This somewhat bewildering work of art pokes fun at her reputation for unruliness, for being unapologetic and open about her sexuality, her smoking and drinking, and use of drugs. It was an anecdote, I read somewhere, and that is indeed how it is structured, with a buildup and punchline. In a retrospective exhibition of Emin’s work, it was placed somewhere in the middle.

Among all of Emin’s famous, intense art pieces—like My Bed, an installation of her bed during a mental breakdown, complete with used and unused condoms, bloody underwear, and empty liquor bottles—it was a welcome moment of reprieve.

In many interviews with Emin, her conscious decision not to have children comes up. As if she has to justify it, which irritates me.

Parenting is the enemy of great art, Emin believes. Art is the birthing.

Not long after the MRI, I turned thirty-three. I thought I would deteriorate and die quickly. That was all I knew about MS, from a distance. My patient records had been lost in the hospital, so there were no specialists who could tell me otherwise. Still, normal life went on, like my rent payments, love affairs and friendships, and cafés that happily ate up my last bits of energy.

It was an extremely strange time.

But when one love affair became serious, the possibility of dying suddenly mattered.

Thanks to my attentive GP, my file was rediscovered and I was assigned a care team at the hospital. With my own neurologist and an MS nurse, new information, and some reassurance. It turned out I wasn’t going to die. At least not anytime soon.

No longer assuming that you will die soon takes some getting used to. Because what can or do you want to put your remaining energy into? Being ill and thinking you are going to die means having to say goodbye to wishes that you didn’t even know you had. Then if it turns out that you’re not going to die soon, some of those wishes become possible again. What do you want to pour your remaining energy into? I wanted children.

While writing this essay, I discovered that motherhood actually awakened something in me. Not great art, but a wish.

Before the birth of my eldest son, I had never written anything besides some practical texts. Barely three months after he was born, I took my first writing class.

While writing this essay, I am trying to recall what my motives were.

An existential crisis, a midlife crisis, and a need for assertiveness certainly played a role, but there was something else too. I write my essays with my sons in mind. What if I, like my own mother, die prematurely? She had just turned forty-nine when she died of an aneurysm.

From my mother I inherited a hair curler, a belt from the sixties, and a diary that I thoroughly comb through once a year. Not a lot. My sons can draw on much more.

After the MRI, another before and after moment presented itself: the hammer.

My Amsterdam neurologist sometimes examined me with a small, irksome hammer. First, she had me do exercises that would not be out of place at a senior citizen’s gym, and then she pulled out her hammer to test my reflexes. A tap on my knee and my leg shot up. I was always amazed at how my body reacted of its own accord to every tap. But during my pregnancy, nothing happened.

The hammer ran through the usual reflexes.

Arm, knee, left foot: fine.

Arm, knee, right: fine. Foot: nothing.

The neurologist and I were shocked. I could see it in her eyes.

“Well,” she said, “you have MS, of course.”

“Yes,” I replied.

My illness is with me all day long, there’s no escaping it, and yet the hammer made me extra aware. It felt unreal that my foot, without my realizing it, was faltering. It felt sneaky and underhanded. My foot had not warned me.

My foot emphasized the unreliability of my body, the sword of Damocles hanging over me. A suffocating feeling.

Shortly after the appointment, I moved to a new city and got a different neurologist. He doesn’t make me do exercises and doesn’t have a hammer either. You don’t always have to know everything.

Koos Breukel says that he photographs people in order to find out if they’ve suffered some form of injury as a result of setbacks in their lives, and “if they have managed to come to terms with this.”

This I found out later, after I stumbled upon my portrait. During the guest lecture, Breukel told the class about his vintage camera, along with the anecdotes behind some of his portraits. He photographed several students, but perhaps because of the scar, my portrait was the only one he kept in his portfolio.

When he took it, I thought I had pretty much come to terms with everything it represented to me: the scar, the dog that bit me, the life I lived and everything that lay behind me. But then the MRI came along and I had to start over again. The dog that bit me was my parents’ tiny, terrible dog. She didn’t like children or people in general. And she didn’t like me especially. I had completely forgotten about her. When I look in the mirror now, I never even see the scar. You could say I’ve come to terms with it. But the MS?

I don’t think I will ever come to terms with it.

✶✶✶✶

Ine Boermans grew up in the Dutch province of Drenthe and studied Media and Art Installation at the Kunstacademie which led her to De Kijkkasten, the open-air gallery in Amsterdam, which she curated and managed for many years. At the age of 34, Boermans was diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis, which prompted her to study fiction writing. Her debut novel, A Long List of Shortcomings was published in 2021 and nominated for the Hebban Debut Prize and Groninger Book of the Year. In 2022, her second novel, Love Interbellum, was published and nominated for the 2024 Amarte Literary Prize. Boermans’ writing has been published in multiple Dutch-language literary magazines including De Internet Gids, Hard//hoofd, Papieren Helden and Tirade. She currently writes a weekly column for the VPRO Gids and is working on her third novel.

✶

Deniz Kuypers is a Dutch-Turkish author of four critically acclaimed novels published in the Netherlands. His writing has also appeared in the Denver Quarterly and Westwind Journal of the Arts. He lives in San Francisco.

✶

Koos Breukel (The Hague, 1962) is a Dutch portrait photographer known for the depth and honesty of his work. Guided by his instinctive abilities, he goes beyond surface appearances, to show what lies beneath. Rather than being harsh or clinical, his photographs offer unflinching yet compassionate portrayals that honor the subject’s individuality, life experience, and above all, their dignity. Breukel has held solo exhibitions at institutions such as the Museum of Contemporary Art in Pori (Finland), the Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris, and the Fotomuseum Den Haag. His work is part of major collections, including the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Dutch Fotomuseum in Rotterdam, the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag, the Frans Hals Museum in Haarlem, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, and the Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris.