University of Nebraska Press, 2025

Robin Hemley’s title, How to Change History: A Salvage Project, is bound to catch the eye of the many readers in this historical moment who feel that the timeline they are trapped in could use some revision. Those readers might not find the step-by-step guidebook they’d hoped for, but if they persist, Hemley will guide them to some ways they can, if not alter the past, at least shape the narratives that surround them in ways that shed useful light on where they are now and how they got there.

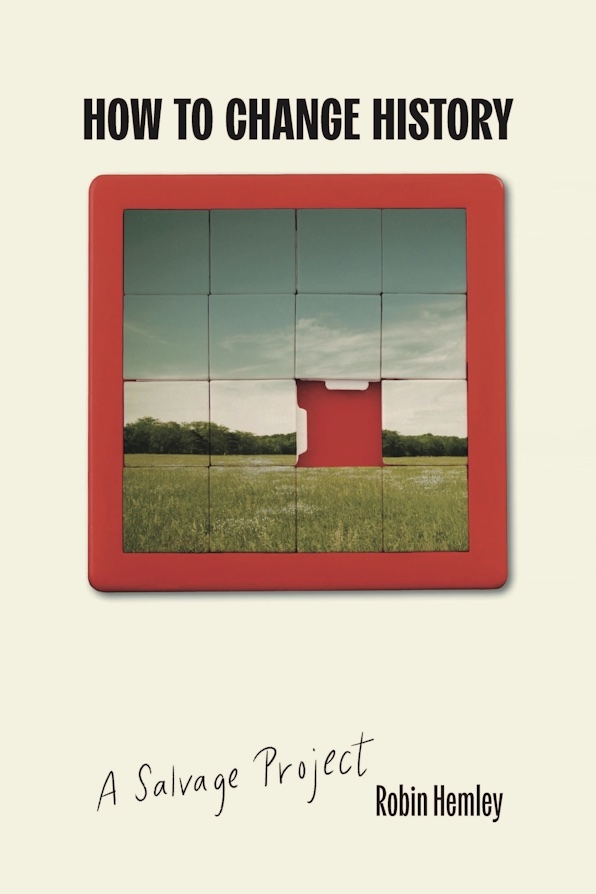

Readers should look to the subtitle, A Salvage Project, which gives an important clue to the true nature of Hemley’s project. It may be a wink at the volume’s collection of pieces, of all shapes and sizes, from moments spanning Hemley’s prolific career. How to Change History is Hemley’s sixteenth book in a career ranging across genres, most recently the autofiction Oblivion, An After-Autobiography (Gold Wake, 2022) and Borderline Citizen: Dispatches from the Outskirts of Nationhood (Nebraska, 2020), essays and reportage documenting the author’s global journey as “a polygamist of place.”

However, A Salvage Project also offers a clue to Hemley’s response to the challenge posed by his title. What Hemley wants us to understand, I think, is that history is made up of the materials all around us all the time. The author’s personal history is documented through the paper trail he and his family have left behind, as their personal and professional lives have taken them across the country and around the world. It’s a complicated and extensive history, given his parents’ involvement in modern American letters in the 50s and 60s—his father a founder of the Noonday Press, and his mother a short story writer who was a resident at Yaddo alongside Theodore Roethke and William Carlos Williams. He discovers that not only the records but also the people behind them are moving targets; even with new facts in place, the larger meanings of personal history can still be interpreted multiple ways, with the truth of any given interpretation remaining elusive. One way to change history for yourself is to gather new information that changes your understanding of the stories you’ve always told yourself, whether it’s about the disturbing sexual politics of Yaddo or your family’s relationship with Head Stooge Moe Howard.

But Hemley’s volume is not just history—it is about history. The things from which history is made, Hemley suggests, can be found in the kinds of events, objects, and landscapes he has noticed, analyzed, investigated, and described in this volume. This historical awareness requires perceiving the things we encounter daily as moments in larger narratives, as simple as contemplating the decline and fall of Judy Garland while watching The Wizard of Oz or as complex as learning the family rituals of a new set of in-laws many time zones away, as small as a forgotten photograph or as sprawling as a master-planned home development. Pausing over these fragments and artifacts, trying to see the larger narratives they emerged from, is a movement towards historiography.

Organizing, pursuing, and documenting that impulse to gather up and contemplate the shards of experience becomes a creative act. “Think of this moment of attention as a light switch, think of it as a toggle between defunctness and relevance. Think of these words as part reliquary, part rescue mission, part memorial,” Hemley tells us in the prologue.

Thus, many pieces have a kind of archival intent, no matter their style or subject matter. The impersonal, observational tone of “In the Storeroom of Figments” transforms the early 80s seamy back-office of Playboy’s Modern Living Department into an ersatz museum collection documenting an unlamented lost archetype, the “Playboy Males,” who liked their softcore pleasures served with a side of aspirational home electronics and cologne. “Jim’s Corner” turns a quest to find out the fate of a campus memorial plaque into a meditation on the ephemerality of any effort to leave a mark, the gap between the longing for some concrete locus of memory and the hard facts of constant change: “Get this: the future doesn’t care.”

The caring is up to us, and the act of caring, Hemley shows us, is what stands between history and oblivion. This is literally the case in Hemley’s reconstruction of his family history, which takes place in the context of his mother’s advancing dementia. But nothing in the volume fully captures this idea that the intervention of the author can switch the toggle from defunctness to relevance as “The Incomplete History of Mary Hilliard,” in which the author executes a close reading of a detailed scrapbook he found at an estate sale in Easton, Pennsylvania, “every page crammed with letters, engagement announcements, the stockings she wore throughout World War II. . . ”

When Hemley explores this scrapbook, which illuminatingly mingles the traces of daily, personal life with the bigger tracks of world events, it is not to solve the riddle of the actual Mary Hilliard (b. 1929), or to celebrate an unusual achievement in the field of scrapbooking—it catches Hemley’s eye precisely for its embodiment of the ordinary way individuals mark their passage through time despite the fact that those marks will end up abandoned and obliterated. “I’m interested in the artifact-ness of this scrapbook . . . the shrines we construct to tell us who we were that we never consider will someday wind up sold to a complete stranger at an estate sale.

”How to Change History: A Salvage Project suggests in sum that the impulse to take available fragments and remnants and from them construct a world and an experience in ways that can survive the test of time is the origin of authorship, and in authorship, the origin of history. In the end, the kind of change to history that Hemley describes and enacts may not magically change the present; we still can’t go back in time and alter the past. But with attention, investigation, and reflection, we can create historical narratives that might help us to understand the present more fully, more generously, and to act accordingly. How to change history: write it.

✶✶✶✶

Douglas Reichert Powell is the author of Endless Caverns: An Underground Journey into the Show Caves of Appalachia (2018) and Critical Regionalism: Connecting Politics and Culture in the American Landscape (2007), as well as many essays about place, space, and region. He teaches writing, literature, and cultural studies at Columbia College Chicago.

✶

Whenever possible, we link book titles to Bookshop, an independent bookselling site. As a Bookshop affiliate, Another Chicago Magazine earns a small percentage from qualifying purchases.