Articulate. My husband has a twelve-inch-tall action figure of me — I’m serious — about the size of a Barbie doll. She is “fully articulated,” which in action-figure speak means that her arms and legs and head can swivel. When he had this made, he had one made of himself, too. It was a passing fad, a kind of a joke between us. Our action figures sit on a shelf in his office. Neither of them speak; they are not that kind of “articulate.” As an actual human, I am very articulate. I speak clearly, have done occasional voice-over work, and can code-switch in and out of academic-speak, Southern-speak, hipster-speak, student-speak, business-speak, and a little bit of French without effort. There are some things, though, that for the longest time I couldn’t say. I could only swivel my arms and legs and head.

Beatles, The. Fill in the blanks however you’d like here, but let me interject that within minutes of picking up drumsticks for the first time (a solid five decades after naming my pet hamster “Paul McCartney”), I realized I’d been paying attention to Ringo’s drumming all along.

Cats. My sisters and I named our first cat Alice, despite the fact that the marmalade tabby kitten was male. After him came Fang, Genie, Geranium, Max, Toonces, Nemo, Chloe, George and Gracie, Maggie, Bird, another Alice, Tina, Trash, Wayne, Ed, Frances, Biscuit, Peach, Rosie. The second Alice liked to sleep on a blanket inside my kick drum. Until, of course, I kicked.

Dancing. When I stood, chin in hand, at the barre, I didn’t notice the rest of the class working diligently through their steps en centre of the practice room. Miss Merilee scolded me by saying, “Real dancers think with their feet.” She’d told us to think about the adages we’d just learned. I quit ballet not long after that. Too tall in pointe shoes, too curvy at twelve, and I never got picked for “The Nutcracker.” I didn’t yet understand non-verbal communication.

Everly Brothers. Of course my freshman roommate and I both came to college with guitars. Turns out we sang together remarkably well; as the Simon and Garfunkel song goes, we “harmonized ‘till dawn.” We sang Creedence, Neil Young, Joni. My roommate could sing the complicated harmony in The Beatles’ “If I Fell,” which I’ve not mastered to this day. We sang the Everly Brothers’ “All I Have to Do Is Dream” and “Wake Up, Little Susie.” I hated that one. My sister’s name was Susie, and by then she had been dead for eight years. Waking up was no longer in her repertoire. “Love Hurts,” however, is still a favorite of mine because of how Gram and Emmylou did it.

Follow Spot. My major in college was mass communications, which to my parents’ chagrin meant television production. They were the rare parents who would have preferred I major in English, instead of a trade. I took a test once about designing a lighting grid, which included correct placement of a follow spot. I think now of the scene in the film “Sunset Boulevard” where Hog-Eye the stage electrician turns his follow spot on Norma Desmond, the silent film star resistant to “talkies,” played by Gloria Swanson. In this scene, she returns to a studio for the first time in years. She is delusional, certain that she’s been given a featured role. No one is willing to break it to her that a prop master merely wants to use her ornate and antiquated car in a shot. Hog-eye keeps the follow spot on her as a courtesy, but she has no value to the production.

Garage Bands. I wish I’d thought to shove my friend L. off his drum throne, sit in his place, and try my hand at the kit. But in my defense, this was high school in the 1970s, when teenaged girls didn’t play drums. I didn’t know then that Karen Carpenter was a mighty jazz drummer, only that her saccharine hit “Close to You” was secretly kind of fun to sing. With my girlfriends, I waited for the boyfriend or the wish-he-were-my-boyfriend in the garage band to put down his guitar, his bass, or step away from the drums. Only then, with a boy’s attention, did I believe I could be heard.

Handler. How do you handle a hungry man? went the Campbell’s soup jingle. The mannnnn handler. The song was not written as a parody of my surname, so I chose to interpret my classmates’ singing the commercial to me as a compliment, a thing from which I could take power. Yep, I could handle a man. I did not yet recognize that I was the hungry one.

Indigo Girls. In my twenties I had a boyfriend who would rush to turn the radio down whenever the Indigo Girls’ massive hit, “Closer to Fine,” came on.

“I can’t believe they’re saying, ‘closer to dying,’” the boyfriend complained. “That’s creepy.”

“The words are ‘closer to fine,’” I said, noticing that the boyfriend had become less fine.

I’d recently met his family in their home in an elegant suburb of Boston. His mother served us dinner in their formal dining room. I remember a floor lamp with a pale pleated lampshade. I remember her nodding in my direction and saying die Jüde as she spoke to her son.

The Jew.

Jew. See above.

Klan, Ku Klux. My father moved his three daughters, my mother, and himself to Atlanta from Detroit in 1965, just in time for me to start first grade. He was an attorney employed by a labor union active in the Civil Rights movement. In our ranch house, with our Oriental rugs and first editions of Langston Hughes poetry and prints of Ben Shahn drawings, my mother neatly clipped an announcement for a Ku Klux Klan meeting from the local paper. She taped it inside the door of a kitchen cabinet, evidence of the whispered menace in the place she found herself raising children. The clipping stayed there until my parents sold the house a decade later.

Love. All you need.

The Moeller Technique. This is a drumming exercise; a kind of whip motion intended to increase a player’s speed and control with drumsticks. Hold the sticks between thumb and middle finger instead of thumb and index finger. Start with the wrist, not the hand. Hit the drum heads slowly until the motion becomes effortless. Repeat. Repeat some more. Realize that this is tedious, that you hate it, that you’re not training to be a jazz drummer or even a performing rock drummer. You just want to have fun.

Noise. I was the rare teen who was never told to “turn off that noise,” when I listened to Cream and the Stones and Elton John and the lesser bands of the era (Bread, America) on WQXI-FM radio (“Quicksie in Dixie”). When my father was in a good mood, he turned The Who’s “Tommy” up to eleven on the family stereo, or roared “Will The Circle Be Unbroken” along with his LP of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band. That said, when my father was raging, my sisters and I were alert to the danger in laughing aloud or speaking above a whisper.

Open-Handed Playing. Instead of crossing your right hand over the snare to hit the high hat, hit the high hat with your left hand. Sometimes it’s easier that way.

Piano. My mother and my sister Sarah played Bach and Satie for four hands on the two pianos in our house: an upright grand in the den, and a baby grand in the living room. I got as far as “Heart and Soul” and the “Pink Panther Theme” on the upright before I gave up. I can’t listen to a Satie Gymnopédie without weeping.

Quiet. A thing that drums are not. I started playing on an electronic kit, the sound sequestered in my headphones. My husband says that he only heard my muted thumping. Desire to claim sonic space led me to buy an acoustic kit, then sell it and upgrade to another (a better snare drum, two rack toms instead of one.) I made an agreement with myself to try heavier sticks (5As instead of 7As) and to hit the heads harder. Abe Laboriel, Jr., Paul McCartney’s drummer, sometimes plays with sticks that look to me like Renaissance Faire turkey legs. Sometimes, though, he uses the soft tone of brushes.

Regret. Not saying “I love you” to the right people. Saying “I love you” to the wrong people. Saying “I know” when I didn’t. Saying “I don’t know” when I did. Not saying “no.” Not saying “yes.” Saying “OK” when it wasn’t. Saying “I’m sorry” because I thought I was.

Standard Tables of Time. My first drum teacher’s specialty was teaching adult women. From her, I learned how to warm up with the Standard Tables of Time. Strike a series of quarter notes once, twice, thrice, then four times in a row. Set my metronome to something easy, maybe 80 beats per minute. Master that, and bring the BPM up ten points. Now ten more. In this way, I control time.

Truth. You don’t want to hear it. It’s sad. It will make you clutch your children, never break away from your lover’s gaze, put your doctor on speed dial. Truth, see also: Take it Out on the Toms, Floor; Take it Out on the Toms, Rack. Better than taking it out on your own body.

Unspeakable. No one actually told me not to talk about sorrow. I knew to stay silent, a rhythm, like a beat, a pulse within me. Your sisters are dying and dead, your father’s a drug addict, your mother is trying to make everything right by folding the laundry just so. “I never knew,” more than one person said to me later, after I’d written a book about it and won some awards for the book and still didn’t feel all that much better. “You were a mess, and I didn’t know why,” a high school teacher told me at a reunion. I didn’t say, “You never asked.”

Virginia, Sweet. My favorite warmup at the kit. A shuffle. When I play it, I wonder what the great Charlie Watts was thinking, barely cracking a smile, never breaking a sweat. Got to scrape that shit right off your shoes.

Whale. What I did to my own face, hair, arms, the wall, a door, a car, handles of vodka, handfuls of pills in my teen years, my twenties, my thirties. Longer. Whale, what I wanted to do to a father, a boyfriend, a teacher, a boss. Wail. My voice when alone.

X, the band. I once saw Exene Cervenka, the singer from the band X, at Barney’s Beanery in West Hollywood. This was in 1982 or ’83. She was eating, or maybe she was playing pool. I forget. From across the room, I studied her Dustbowl-Gone-Cool attire, her carefully tousled hair, her general “fuck you” vibe. I wanted to say that very thing to almost everyone. I wanted to know how she did it.

Youth. Both my sisters died in their youth, each of illness, one rare, one common. This is called out of order death; children are not “supposed” to die before their parents, or their older sister, for that matter. Nonetheless, they did. Their youths were hospital-proximate, hospital-often, hospital-usually. In my youth I feared for them, for myself, for our parents. Who also, by the way, also died relatively young, though not in their youth.

Zero. What comes before the four count, the silent starting point in my head before I hit my sticks together and begin to make noise.

✶✶✶✶

Jessica Handler is the author of the novel The Magnetic Girl, winner of the 2020 Southern Book Prize, a 2019 “Books All Georgians Should Read,” an Indie Next pick, Wall Street Journal Spring 2019 pick, Bitter Southerner Summer 2019 pick, and a Southern Indie Booksellers Alliance “Okra” pick. Her other books include Invisible Sisters: A Memoir, and Braving the Fire: A Guide to Writing About Grief and Loss. Her novel The World To See is forthcoming from Regal House in 2026. Her nonfiction has appeared on NPR, in Tin House, Drunken Boat, The Bitter Southerner, Brevity, Creative Nonfiction, Newsweek, The Washington Post, and More Magazine. She was the SP ’23 Ferrol Sams, Jr. distinguished writer in residence at Mercer University in Macon, Georgia, and is faculty member at Etowah Valley MFA at Reinhardt College. Jessica lives in Atlanta with her husband, novelist Mickey Dubrow.

✶

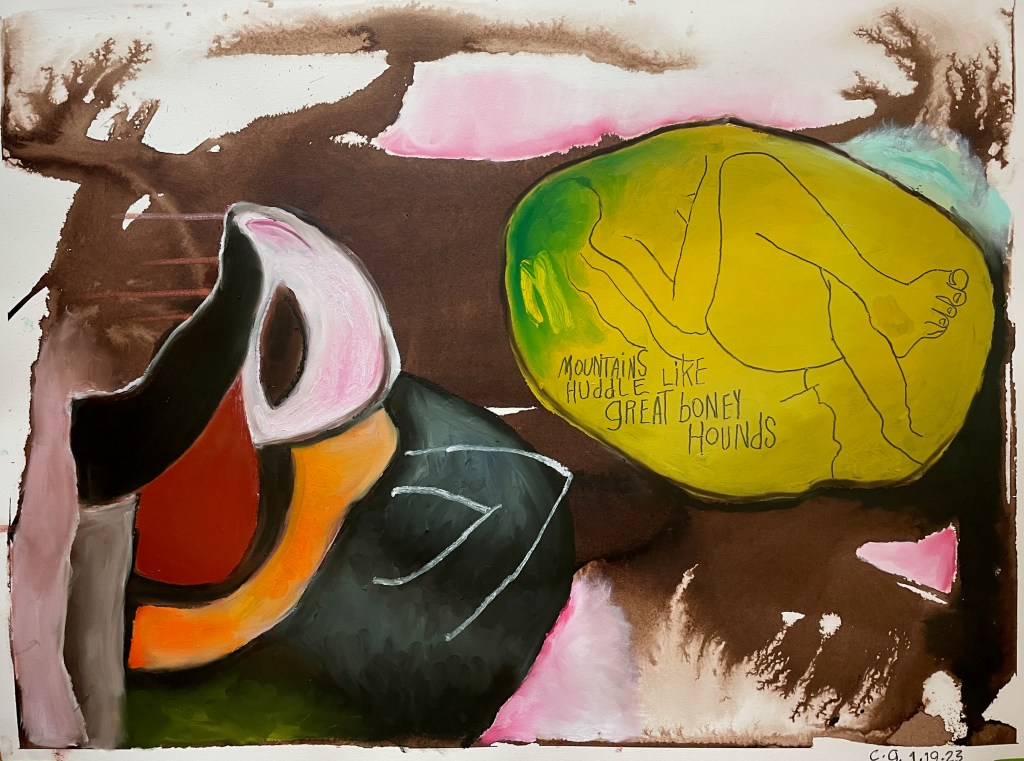

Char Gardner is a lifelong visual artist and CNF writer, who taught in the Washington, DC area for nearly twenty years before she began working with her husband, Rob Gardner. Together they made documentary films internationally for over thirty years. Now retired, they live in the Green Mountains of Vermont, where Char is at work on a memoir. Her recent drawings are made with oil sticks on Arches 22×30 paper. Imagery is derived from the human form (working directly from a live model) and from the surrounding natural world. Her essays have been published in The Gettysburg Review, Green Mountains Review, and elsewhere.

✶

Whenever possible, we link book titles to Bookshop, an independent bookselling site. As a Bookshop affiliate, Another Chicago Magazine earns a small percentage from qualifying purchases.