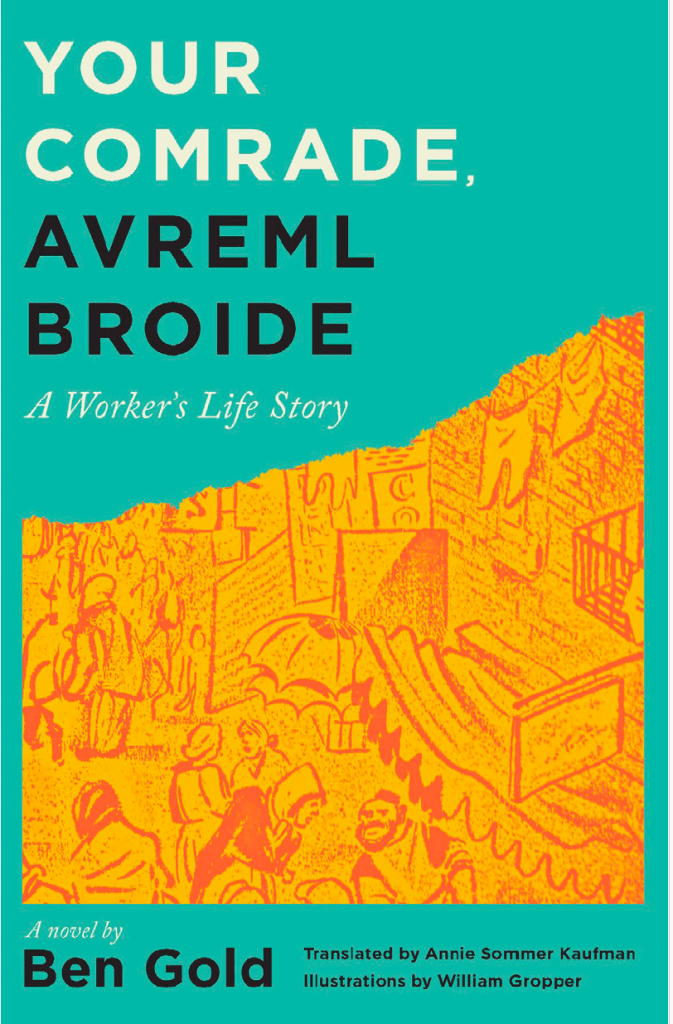

Forthcoming from Wayne State University Press, November 2024

Original Yiddish text available here for “Your Comrade, Avreml Broide”

Ben Gold, the president of the Fur Workers Union, was one of the boldest and most beloved labor leaders in the US. He was born in Bessarabia in the Russian Empire in 1898 and immigrated to the US with his family in 1912. He worked in the fur industry and served as the president of the International Furriers Union. With his legendary skills as an orator and negotiator, he organized the fur workers for better wages and conditions through the defeatist 1920s and resurgent 1930s.

His first novel, written in 1944, Your Comrade, Avreml Broide is a working-class, coming-of-age novel that traces the family origin, immigration, and radicalization of an everyman named Avreml Broide. Mirroring Gold’s own life, Avreml’s story begins entangled in a complex intergenerational social and criminal community in Bessarabia just after the turn of the twentieth century. Personal dramas drive a young Avreml to New York City in his young adult years, where he finds a job in the fur industry and devotes himself entirely to his union, party, and the fight against fascism, often to the detriment of his personal life and relationships. Through strikes, dissidence, and finally on the front lines of the Spanish Civil War, Avreml’s journey presents the fascinating ambiguity of subsuming the self in service to party discipline.

The excerpt below is the first chapter of the second half of the novel, after a heartbreak convinced Avreml to leave his loving family and community in Bessarabia. He finds New York City—and the dynamic between workers and bosses there—stifling and depressing. Avreml struggles to “find his way,” and like Ben Gold and millions of other immigrant laborers, joins the union, where he builds his own identity, purpose, and sense of belonging. The politician whom he hears speak at his first union meeting is a reference to Congressman Meyer London of the Socialist Party, who represented the Lower East Side of Manhattan in the US House of Representatives in 1915– 1919 and 1921– 1923. London was a key figure in Gold’s political development, but as Gold reported in his memoirs, betrayed the fur workers in the legendary strike of 1926.

America didn’t go as well for Avreml as he had imagined. The assimilation process was hard for him, and it was difficult to feel at home in the big city of New York. The large tombstone-like buildings threw him into a panic. His dark little room, with its itty-bitty window blocked by a brick wall, enclosed him in loneliness like a prison cell and drove him out to the street. Out there, the wild commotion and the strangeness of the streets drove him back into the dark little room.

He had a hard time uttering the few English words that he had toiled for weeks to learn. He began to lose hope of ever learning the difficult, weird language.

He also didn’t have any luck finding a job. He worked at pey-per bok- ses, at po-ket-boox, and at a dozen other jobs before he finally succeeded in learning a treyd. A guy from the old country brought him into a shap where they taught him to become a for-ree-er and make coats from pelts. He had to work four weeks for free and pay ten dollars on top of that. He felt satisfied though, knowing he would finally have a trade under his belt and could start making a living.

Avreml hated the shop. He hated the discipline of the shop. He couldn’t stand how the workers feared the bos, who ran around like a wildman among the workers all day grumbling, “Get a move on, the day’s not standing still!” He couldn’t understand why the workers shuddered to speak a word to each other, why they had such a fear of the boss, that skinny pale little guy who never got tired of running around the shop, eyeing the work and watching each laborer’s movement. It was crowded in the shop, with the tables and machines arranged so close to each other—on purpose, so the boss could have each of them under his eye. The floor was cluttered with heaps of pelts and partially sewn coats. Wet coats lay by the nail boards, having been soaked to become softer for nailing. Next to the tables, at which the kat-ters stood to cut, and next to the machines on which the op-per-rey-ters sewed, lay little pieces of cut- off fur mixed up with staples, which the cutters had used to pin one pelt to another. Piles of fabric scraps, trimmed from the linings, lay next tomthe fee-nee-shers’ tables. Little nails that the nailer had used were scattered all over the floor. The entire dirty shop had a coating of hair dust from the fur. The windows were always dirty. In the hot summer days, the shop was unbearable. Hot air and dust bit at your nose and poked your throat. Sweat streamed like water. The fur’s cheap dye colored the workers’ moist hands and got smeared across their faces. Avreml grew to fear looking at the workers. What made the worst impression on him was when the workers consoled him by saying, “Don’t worry greenhorn, you’ll get used to this misery.”

In the evenings after work, Avreml would go out on his building’s ruf to cool off from the heat and to breathe in a little fresh air. The nights were even harder than the days. Freed from work, he gave himself over to his longing for the shtetl. His homesickness tortured him to tears. He missed the wide green fields where he strolled on cool summer nights, the smooth spacious river where he used to swim worry free on summer nights and on Shabbos. He missed the cool, fresh water and pouring it into the heavy wooden bucket. He missed his father and mother, his friends, and he was just dying from yearning for Rivele, whom he loved now more than ever. The nights were simply painful for him. His tired limbs pulled him toward sleep, but his longing for home and his regrets about losing his mind and coming to America wouldn’t let him fall asleep. He isolated himself from everyone and didn’t make any friends. He was all alone in the big city of New York, lost in his loneliness and seclusion. He gave himself over to his yearning and his regret with a painful plea- sure. Stubbornly, he avoided the amusements of the big city and the big country so he could rescue himself from them and return home as soon as possible.

At first, he thought of going to Brazil or to Argentina, but he realized those were empty thoughts, and he was just fooling himself. In truth, he really wanted to go home, to the shtetl where he was born, where he grew up, where everyone knew him and he knew everyone, where life flowed restfully and without worry, among his own people and friends. But how could he go home? How would people look at him in the shtetl, and would Rivele forgive him for hurting her like he had and then leaving without saying goodbye? He thought about it and thought about it, and “Get a move on, the day’s not standing still!”

He couldn’t find any answer. He frightened himself with the thought that he would have to stay in America. He often asked himself disapprovingly what made him so different from his acquaintances. They were all so satisfied with America and wouldn’t go back home for anything. He was the only one who tortured himself and couldn’t adapt to the new life. He tried to force himself to adjust to the strange land with such thinking, but the shop, the gloomy room, and the loneliness drove him back to his homesickness.

Avreml’s nerves were getting more and more rattled. He began worry- ing about his health. He knew that no doctor would be able to help him. “Ach,” he said to himself, “if only I had a friend, someone I could speak to from the heart, then it would probably be easier.” But where do you find a close friend like that, someone you can talk to freely and frequently, someone who will understand?

Morris, thought Avreml, is the only one I could complain to. Smart and experienced, Morris would definitely understand. But he didn’t know how to approach the topic. Morris worked with him in the shop. He was a cutter. A tall, big-boned, middle-aged man, always neatly dressed, with a kind, masculine face and friendly black eyes. Morris gave the impression of a worldly person with a lot of life experience. All the workers in the shop treated Morris with respect. Even the boss, Morris’s uncle, treated him differently than the other workers. The boss never dared tell him to “get a move on.” To Morris he spoke with dignity, like he would to one of the bay-yers who purchase for large companies, or to the president of a bank. He consulted with him about the business. If a fight broke out between two workers in the shop, Morris could smooth out the conflict because the workers gladly deferred to his reason and fairness.

From the first time Avreml saw Morris, he took a liking to him. When- ever he would ask, “Nu, Avreml, how’s it going in America?” Avreml could hear a special friendliness in his voice.

He made up his mind that he would wait for Morris at the shop after work, spill his heart out to him, and ask for some advice. But he put it off day after day because he couldn’t work up the courage to have that kind of a conversation with Morris. Even so, just the decision to talk it through with Morris calmed him a bit. Once, when his homesickness had set in on torturing him again, Morris’s image started swimming in front of his eyes, like a loyal ally in a hostile land. Finally, he decided that tomorrow he would tell Morris he wanted to talk to him after work.

That day, Avreml got up earlier than usual. He got dressed quickly and went out to the street. It was still early, but the sun was already burning the stone city, which hadn’t even cooled off from the night’s heat. All over the streets, people were walking to work with slow, sleepy strides. In their damp faces, Avreml saw their exhaustion from the suffocating sleepless night.

He went into the little restaurant across from the shop, took two rolls, a butter pat, and a cup of coffee, then took a seat by a little table away from the other people sitting at their little tables and sluggishly eating their meals.

Morris came into the restaurant with his typical firm and confident steps. He took a cup of coffee and nodded to the people who were sitting at the little tables with a long glance. He noticed Avreml, sitting alone at the little table and approached him.

“May I sit next to you Avreml?” he asked in a cheerful friendly voice. “Certainly,” answered Avreml, pleased and blushing.

Morris hadn’t waited for his answer. He pulled out a chair that had been pushed under the table, made himself comfortable, and began slowly sipping his coffee. Abruptly, he let out a quick question, “So, Avreml, have you made your peace with ‘Columbus’s Country’1 yet?”

The directness of the question shook Avreml. He was pleased that Morris had sat down beside him. It gave him a thrill that he was speaking so formally to him. It showed he respected him. Morris didn’t wait for Avreml’s answer, and continued talking between one sip of coffee and the next. “You’re not the first guy to have a hard time adjusting to life in America. It was rough for me, too, my first couple of years. I was home- sick. I didn’t want to stay here for nothing. I thought this was a wild place.”

Avreml slurped up Morris’s words.

“But now,” continued Morris, “I wouldn’t go back for nothing, not even if my entire hometown sent for me. That’s just how it goes Avreml.”

He pushed aside the emptied coffee cup, turned his face to Avreml, looked him right in the eye, and said pointedly, “Avreml, America is the finest country in the world. My uncle’s dirty shop isn’t America. Work- ing at my uncle’s shop, which is truly a torture, is not America. Here in the New World, life flows with a mighty force. Everything that goes on here is in order to make the worker’s life easier and better. You Avreml, you’ve got to adjust to this life. You’ve got to forget your hometown, and you’ve got to find your way into this beautiful and fruitful American life. It will get better.”

Avreml couldn’t get over his surprise. How did Morris know his thoughts about what a hard time he was having, even his homesickness, and his opinions about America? With a stammer, he asked, “So, how does a person find his way?”

Morris was silent for a while, smoking a cigarette as he gazed into Avreml’s face, and in a confident, even commanding tone told him, “Sign up to the union! Tomorrow night after work there’s going to be a mass meeting at Cooper Union Hall.2 Come to the meeting.”

He offered Avreml a pamphlet calling all furriers to the meeting. “Nu, it’s getting late, let’s get back to our slave labor,” he said, ending the

conversation. They left the restaurant and went up to the shop.

Avreml knew the trade had a union. From listening to the talk among the workers, he had gathered that after losing the strike in 1920, the union had become so weak that it had completely lost control of the shops. He also knew that his shop was one of the many that didn’t belong to the union, and that his boss was one of the union’s stingiest opponents.

Avreml didn’t have anything against the union. In fact, he had even considered becoming a member. But for the life of him, he couldn’t under- stand how the union would help him with his personal problems. At the same time, he was sure that Morris was smart and wouldn’t give him any useless advice.

Avreml waited impatiently for the mass meeting. He was one of the first to arrive at the enormous Cooper Union Hall and chose a seat close to the platform. Little by little, the hall filled with workers. The place started to buzz. The workers were all speaking to one another in loud voices. Avreml sat by himself and observed the others. He hadn’t known there were so many furriers. He found it strange how different they looked compared to the workers in his shop. They were all clean shaven and neatly dressed. They laughed and joked with their friends and neighbors. Even sitting still and silent, he felt like one of them, and he started to feel love for this lively and sociable mass of workers.

A few people appeared on the platform. Loud applause broke out in the hall. When the chairman banged his gavel on the podium, the buzz cut off, as if by a knife. A resolute sincerity took over the faces of all the assembled workers. The chairman, a person in his fifties, seemed calm and relaxed. He explained that ever since the failed strike, the union had grown weaker, and the number of non-union shops had increased so that those thousands of workers weren’t paying dyuz to the union. He explained that the bosses knew what state the union was in. They knew that the union didn’t have enough power to protect the worker, and they used the situation to their advantage, reducing wages and extending working hours. There was a danger that the old slave wages, which used to rule the trade before the union was founded, would be reinstated in the shops. He also announced that the travesty of home work was starting to get reintroduced in the trade. He ended with a rousing call for the workers to join the union once again and refortify the organization so they could bring back union wages, union conditions, and union control to the trade. The workers ardently applauded the chairman.

After that, he introduced a union official as the next speaker. This one spoke in English. Avreml didn’t understand all of it, but he was fairly cer- tain that he was saying almost the same things as the chairman had before in Yiddish. When the speaker was finished with his speech, the chairman banged his gavel and asked everyone to come to order because the next speaker was the great worker-leader who had helped build all the needle- trade unions, “The dedicated friend of the Furriers’ Union, the great leader of the Socialist Party, beloved to us all, Mr. M.”3

A thunder of applause broke out in the hall. The speaker approached the podium. Avreml took a good look at him. He was just a bit too tall to be called short, and was thin and straight as an arrow. He had a noble face and wore gold-rimmed eyeglasses on his narrow, pointed nose. The speaker removed his eyeglasses, set them inside a leather case, and put the case into the upper pocket of his jacket. While the speaker was calmly dealing with his eyeglasses, he spoke softly, richly, with a pleasant, unpolished voice. He said that when he comes to speak to the furriers, they clobber him, but he feels at home. The audience laughed. But when he goes to speak to the bosses, he said, they don’t clobber him, yet he feels beat up. “What good is your applause though?” he said. “Better you should build a robust union and I will applaud you—and the bosses will stop beating us all up.”

“In election times,” he complained, “it’s more of the same. I speak before large enthusiastic crowds and receive hearty applause, but my opponent, the bosses’ representative, receives the votes when el-ek-shen day comes. Now he sits in Congress, and I, your true representative, sit at home.”

Again, the audience gave an affable laugh. Avreml didn’t understand why they were laughing. To him, this sounded like a serious and sorrowful matter that wasn’t appropriate to laugh at.

Abruptly, the speaker let out a bellow:

“You laugh? This is not a joke! It is time for the worker to wake up to the sad truth already!”

His calmness vanished. He was shooting his words into the crowd like hot bullets from a gun. Avreml got swept up in the speaker’s passionate, insightful, and forceful speech. He observed how his thin, noble face burned red with fire. His voice rose higher and higher and thundered with power. Avreml sat hypnotized. The speaker’s words streamed right1 into his heart and his mind. He could have sat and listened to him all night long.

Then, unexpectedly, the speaker began speaking in a softer, more lyrical voice. He spoke of how the time was not far off when the working class would be organized and would seize the entire government apparatus in its own hands, abolishing slavery and exploitation. It would end bloody wars and lead us to a world of justice, fairness, brotherhood, culture, peace, and progress, to the world of socialism.

When the speaker finished, the hall thundered with applause. Avreml woke, as if from a deep sleep, and clapped his hands with all his might. His clapping rang out over the entire hall.

When he stepped out of the hall, he sensed a great energy filling his limbs. He knew that something had happened to him, but he couldn’t tell just what it was. He walked through the streets with such ease and vitality he felt as if he were floating on air. The big city streets and the tall build- ings, which had always seemed like gravestones to him, and the bustle of the street, which he had found so odious, suddenly became genial and cozy. Everyone he saw seemed like a dear old friend.

Now Avreml understood Morris’s wisdom in advising him to attend the meeting and join the union. He recalled Morris’s words: “You’ve got to find your way into American life.”

He started talking to himself, not noticing that the people walking by were staring and smirking at him. “Thank you Morris, my friend. Thank you for showing me the way.” Now for the first time, he could fully under- stand what Morris had meant when he said his uncle’s dirty shop is not America. He thought: how different the workers looked at the assembly! Nothing like in the shop. There in the shop, fear of the boss dominated. Everyone hurried to get as much work done as they could, and each person’s face was smeared with subjugation. It was every man for himself there, and every one of them was a part of the machine. But at the meet- ing, it was an entirely different scene. There, each person was a part of the broad, brotherly, genial mass, throbbing with excitement and strength. Speech, feeling, excitement—the workers had understood the speaker so well! Avreml had also understood each word, even though he had never heard a speech like that before.

Avreml had experienced everything the speaker said as so clear, so elemental. It was only natural that the workers should absorb his words in a still tension and applaud him so fervently. How would it even be possible not to be in agreement with such a speech and with such people? He recalled how he himself had suddenly stopped feeling like a stranger among the workers, and how his loneliness completely disappeared, and he had become his own person, just like the people sitting around him. He felt embraced by a queer warmth and a close- ness toward all of them. He had an urge to scream out his joy, but together with the others, he squeezed out the joy into hand clapping, and the clapping lifted him even higher, making it seem even more like a holiday.

So this is America! he thought. This is what Morris was talking about: workers’ meetings, unions, freedom, equality, brotherhood, socialism. It’s won- derful! His muscles tightened with a swelling energy. He could sense his blood flowing hotly through his veins. It seemed like he was truly seeing the world in its full light. Everything looked brand new to him, as if he were seeing it for the very first time. He understood now that America wasn’t at all what he had thought. Now he freshly understood that America was, as the speaker had said, not only a new land but also a continuation of a great beginning, and that it would lead to tremendous developments. And everything depended on the workers!

Avreml’s resentment of America vanished. So did his homesickness for his little hometown. He could tell that in this new America he had become a new man, completely unlike the Avreml of yesterday.

Tomorrow, yes, tomorrow morning, he thought, I’m going to go up to Morris in the shop and tell him softly, but firmly, “Mister Morris, I’ve made my peace with Columbus’s Country. I’ve found the way!”

1 A colloquial term for the United States.

2 A 900-person auditorium at Cooper Union College in New York’s Lower East Side. Many labor unions, including the Furriers Union, and notable progressive speakers used the hall for mass meetings.

3 Meyer London, Socialist Party congressman representing the Lower East Side of Manhattan in the US House of Representatives in 1915–1919 and 1921–1923.

✶✶✶✶

Annie Sommer Kaufman is a Chicago based Yiddish teacher and translator, as well as Svara-trained Talmud teacher. She spent a year with the Jewish community of Moldova, where she studied Yiddish with Yekhiel Shraybman, before working a decade in the fashion industry as a pattern maker. She organizes with Jewish Voice for Peace.

Photo Credit: Hana Shapiro

✶

Ben Gold, the president of the Fur Workers Union, was one of the boldest and most beloved labor leaders in the US. He was born in Bessarabia in the Russian Empire in 1898 and immigrated to the US with his family in 1912. He worked in the fur industry and served as the president of the International Furriers Union. With his legendary skills as an orator and negotiator, he organized the fur workers for better wages and conditions through the defeatist 1920s and resurgent 1930s. A member of the US Central Committee of the Communist Party, Gold was forced out of the labor movement by the Taft Hartley Act and the second Red Scare. After he defeated his FBI charges through a Supreme Court appeal in 1957, he retired to Florida and continued writing Yiddish novels until his death in 1985. Avreml Broide was his first novel, published in 1944.