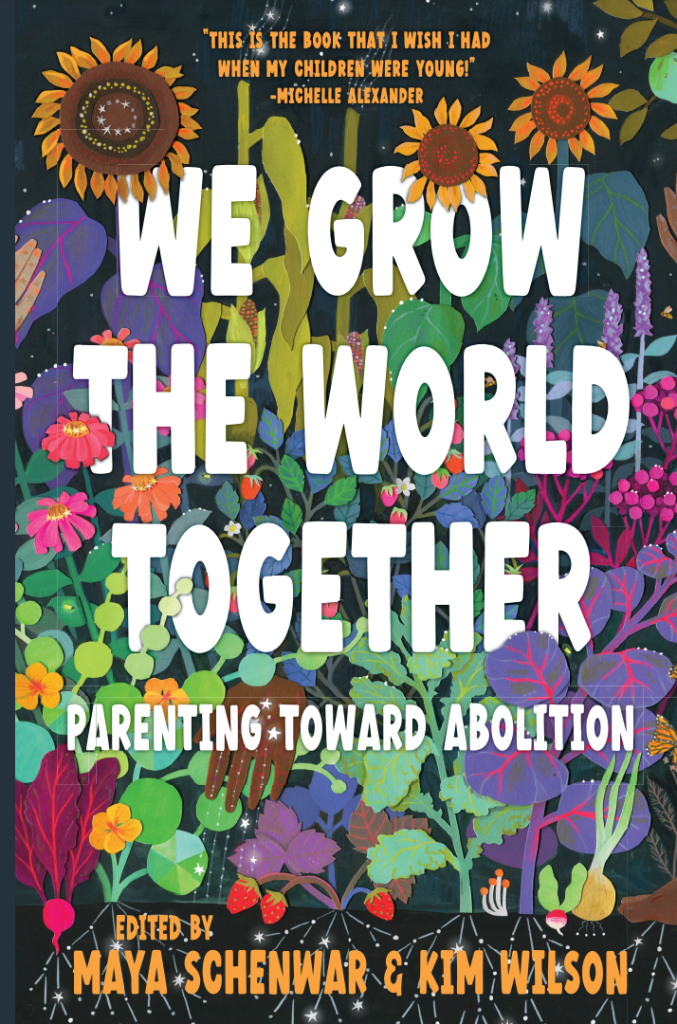

We Grow the World Together is an anthology examining the intersections between caregiving and the movement to abolish the prison industrial complex. We brought together these authors, whose pieces range from personal narratives to activist chronicles to policy analyses, to reveal how parenting—in all its forms—intertwines with struggles for liberation.

This book contains contributions from Keisa Reynolds, Harsha Walia, Beth Elaine Richie, Dorothy Roberts, Mariame Kaba, Ruthie Wilson Gilmore, Heba Gowayed, Dylan Rodriguez, adrienne maree brown & Autumn Brown, Nadine Naber & Stacy Austin, Anya Tanyavutti, Paul Lacombe, Shira Hassan, Sarah Tyson, Bill Ayers & Bernardine Dohrn, Jennifer Viets, EJ, Holly Krig, Ryann Croken, Rania El Mugammar, Victoria Law, and many more.

We offer this collection as an antidote to the erasure of parents, caregivers, and all those who do care work in our movements, as we build a more liberatory world together. In the following excerpt from the book, writer and organizer Keisa Reynolds shares their journey along the uncharted path of pregnancy and parenting as a nonbinary person, which holds parallels to their journey toward becoming an abolitionist.

He Calls Me Zaza: A Nonbinary Road Map to Liberation by Keisa Reynolds

My toddler Bailey will tell you that he does not have a mom, he has a Zaza.

I carried him for nine months and had a C-section after fifty-six hours of labor (yes, I know). Five days after his birth, I experienced the largest, most unexpected bowel movement, it was almost as life-altering as having a child. During my pregnancy, I didn’t eat sushi, eggs benedict, or deli meats. I reduced my alcohol and weed consumption to nearly nonexistent amounts. Until his arrival, I worked a full-time job and a part-time job to save up for parental leave. I made the necessary sacrifices.

I am still not his mother. My son is right; he has a different kind of parent. He has a father and he has his Zaza.

I always knew that I didn’t want to be a mother. I never desired to be a mother. I didn’t want to be one even after falling in love with a man who wanted nothing more than to be a father. I wanted the responsibility of taking care of a child eventually, but I did not want to be a mother.

Then I got pregnant. I tried to think of myself as a different type of mom. There are plenty of people who don’t fit the vision for what our society considers a mother. There are moms covered with tattoos and piercings. There are moms who rely on professional childcare to help make their careers successful. There are moms embroiled in custody battles with co-parents or the child welfare system. There are moms who are not biologically related to their children. There are moms whose sperm helped create their child. There are mothers who fight for the right to call themselves such. Each day, these mothers find themselves at odds with a society that refuses to allow them to shift the narrative of motherhood.

I felt frustrated that I couldn’t imagine motherhood for myself, even though motherhood looks different for everyone. I tried to convince myself that internalized sexism had me underestimating the significance of motherhood like the rest of our patriarchal society. I thought I should’ve wanted to join the club, because it is important. Necessary! Political, even! People are constantly undervaluing mothers and their contributions everywhere. But still—I wondered why motherhood was the only club available.

I decided at the beginning of my pregnancy that my child would call me anything but mom. My friend Byul and I searched Google for nonbinary options. Zaza was one of the many names that sounded silly or didn’t fit my personality. It didn’t help to practice saying alternatives out loud. Exploring multiple options, I pretended to introduce myself to pediatricians in the future. Nibi didn’t work. Neither did Nini or Nopa. It wasn’t until I stared at myself in a mirror, imagining how I would introduce myself to the baby, that I decided on Zaza.

Soon after, my husband Larry began correcting OB/GYNs and nursing assistants during every appointment when they asked, “How are you, Mom?” Eventually, I told him to give up because I was neither the medical staff’s mother nor their Zaza. My protection over Zaza was recognition that the name belonged to our unborn child as much as it belonged to me.

Birthing a child taught me more than I expected about my gender identity. Although I had started to understand myself as nonbinary by time I was twenty years old, I didn’t have an attachment to it. I accepted all pronouns without feeling the pains of being misgendered. After college, I grew more amicable toward womanhood and relied less on gender norms to give me a sense of identity. At times, I aligned with womanhood only as a political identity because it felt easier to explain. Most of my social interactions happen the way they do because people see me as a woman. I understand intimately how our society makes demands of women and creates the conditions that make it impossible to meet them. Being seen as a woman has been more of an annoyance than suffocation—until I became pregnant. I quickly felt lonely as a pregnant person who would not be a mother. I didn’t have a model for parenthood that existed outside of fatherhood and motherhood.

I also didn’t want health care professionals to treat me differently due to my nonbinary identity. I had the privilege of passing as a cis woman. Disproportionate maternal mortality rates indicated that most medical professionals already didn’t know how to properly treat Black women. I feared that being a nonbinary, Black birthing person would encourage further negligence.

At the same time, choosing to be Zaza was something within my control. I knew it wasn’t fair to consider choosing a term of endearment for myself as silly. I wouldn’t think that about other nonbinary people, so should I think that about myself? I rejected the label “femme” years ago, but other people often view me this way, and it is what makes most people see me as a mother. However, after seven years of identifying as nonbinary, I decided that my pregnancy was an opportunity to step fully into myself.

After the ultrasound during my second trimester, Larry and I decided not to tell anyone that we planned to assign our baby as male. I was hesitant to label Bailey even when he was born. From the start, family members would say, “Oh, that’s how boys are!” I was under the impression that all babies liked to sleep, eat, shit, and cry during the exact precise moment when their parents finally lay their heads on a pillow. You mean to tell me that it is just the patriarchy teaching Bailey how to assert dominance?

Being Zaza allowed me to give my child one of many road maps to liberation.

Zaza was one of Bailey’s first words. It is what his father and grandparents and other trusted adults call me. There was no confusion until he attended day care, beginning after his first birthday. It took only weeks before he started to recognize that his peers said Mom, Mommy, Mama, but not Zaza.

He started to point out mothers in the books we read together. There were two weeks when he wanted us to read only Lesléa Newman’s Mommy, Mama, and Me. He would stare at the two moms and stare back at me, as if to say, “I think you are them, but you’re not. You’re a different kind of mother. Are you supposed to be my mother?”

A few months later, Bailey started to call me Mom and every variation of it. He would fuss and squirm whenever I tried to style his hair. Armed with a hairbrush and moisturizer, I chased after him as he ran through our apartment with his arms in the air, yelling, “Mom! Mom! Moooom!”

To my relief, he was only going through a phase in which he thought anyone who cared for him was Mama. Eventually this included Larry, whom he had called Daddy as soon as he could. Neither of us went by Mama, but we understood our little one’s logic. We practiced: You are Bailey. He is Daddy. I am Zaza. Zaza. Yes, you’ve got it. Zaza.

Stella Brings the Family by Miriam B. Schiffer was the first book that got him to understand the best he could that not everyone who does what I do is a mother, myself included. Some nights, my husband and I would hear him call for “Mommy” or “Mama” from his bedroom. We looked at each other and waited to hear Bailey correct himself. Finally, he would remember: He calls me Zaza.

At three years old, Bailey is confident in the fact that I am his Zaza. He corrects anyone who tells him that he means Mom. He has and will continue to process what it means to have a Zaza. He gets to grow up with an example of a queer, nonbinary parent.

Every time someone tells me I am making life difficult for him, that “Mama” is easier and normal, they are telling me to encourage my child to make himself smaller and digestible. That I won’t do. Our family cultivates a home where people explore their identities and express them however they please.

Zaza gives me a name for my role in my child’s life, one that is special and unique and is not one-size-fits-all. Zaza allows me to create my own path for parenthood. It is isolating at times; I often find myself reimagining a world in which Zaza holds as much weight as Mom or Mommy.

This path is much like my abolitionist journey, in which I’ve had to reject everything that I was told was meant to keep me safe. It is not as easy to describe how I feel as a nonbinary person, and adding a child into the mix almost felt unfair to him—how could I ask someone who doesn’t quite understand how the world works to take up the cisheteropatriarchy? But I realized that an abolitionist world—a world that prioritizes self-determination, including gender self-determination—is the one in which I want to raise my child. Discomfort has given me more freedom than I ever could’ve imagined. Stepping outside of the status quo has allowed me to redefine what it means to be a parent without forcing myself into categories that do not define my life or how I see myself.

I used to tell Bailey that he had a different kind of mother because I didn’t want him to feel left out. At the same time, I think that I was also worried about fully embracing not being a mother. I did not want to be put in another “Other” category, and I didn’t want my identity to be another barrier for my biracial Black child. But by saying that he does not have a mom, Bailey gives me permission to see myself for who I am, for the love and care that I provide.

I have to admit that motherhood is still the only parent road map that I know. I’ve veered off course, with no map, because my life doesn’t reflect most of what I’ve seen. I am certain that my version of parenthood is the one I want. Nothing has given me greater pride than a small child with wide eyes jumping on top of me and calling me Zaza as I narrowly escape his sticky fingers and his kisses from a food-stained mouth.

Bailey calls me Zaza, because his existence gave me the permission I shouldn’t have needed. Thanks to him, I get to say no, this is who I am, whether or not anyone else approves.

This is who I am, because this is what my heart knows.

✶✶✶✶

Keisa Reynolds is a writer and storyteller born and raised in Richmond, California. An abolitionist since 2014, Keisa was an organizer with We Charge Genocide and founding member of Just Practice Collaborative. Until recently, they served as the Executive Director of Chicago Community Bond Fund.

✶

Maya Schenwar is the co-editor of We Grow the World Together: Parenting Toward Abolition. She is also the coauthor of Prison by Any Other Name and author of Locked Down, Locked Out. She serves as director of the Truthout Center for Grassroots Journalism. She lives in Chicago with her partner, child, and cat.

✶

Kim Wilson is an artist, educator, writer, and organizer. She is the cofounder, cohost, and producer of the podcast Beyond Prisons. Dr. Wilson has a PhD in urban affairs and public policy. Her work focuses on examining the interconnected functioning of systems, including poverty, racism, ableism, and heteropatriarchy, within a carceral structure. Her work delves into the extension and expansion of these systems beyond their physical manifestations of cages and fences to reveal how carcerality is imbued in policy and practice.

✶

Whenever possible, we link book titles to Bookshop, an independent bookselling site. As a Bookshop affiliate, Another Chicago Magazine earns a small percentage from qualifying purchases.