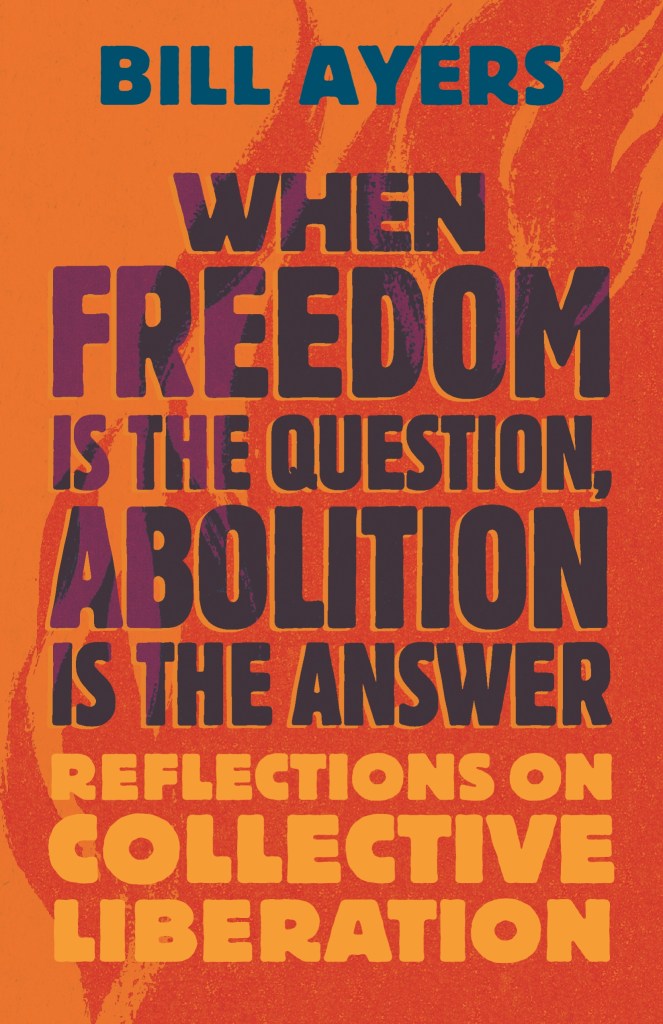

Bill Ayers’s new book, When Freedom is the Question, Abolition is the Answer: Reflections on Collective Liberation, asks these essential questions: What is freedom? How do we get free? In this excerpt, Bill shares reflections that incorporate history, political theory, literature, and his own personal experience within social movements, which come together to offer a radical vision for a more just and equitable world.

✶

— Reflection Two: Freedom’s Paradox —

At the 1968 Democratic Party Convention in Chicago, I was arrested with an unruly mass of other people in a chaotic street fight with the police on Michigan Avenue. Packed into a crowded police van rushing headlong toward Cook County Jail, I was, somewhat oddly, filled with energy and hope—in fact, I felt a little ecstatic. It was the strangest thing, that feeling, and it puzzled me. We had not backed down, true, and we had not run away; we had stood up for peace and for freedom, and we’d conveyed our urgent message to a vast audience. On the other hand, I was bloodied and bruised, wounded and hurting. The whole world was watching that night, and in that dark and stuffy van, holding a rag to my bleeding head, I felt myself breathing the refreshing air of freedom as if for the first time.

This paradox lies at the very heart of freedom: We are perhaps most free when we’re standing in front of an imposing wall, naming a roadblock to our own (or to our neighbor’s) full humanity and then throwing ourselves against that obstacle. The moment may appear obstructed or fraught or frightening or dangerous—it may, in fact, be all of those things at once. And yet freedom pitches into view precisely when unfreedom is identified (enslavement, subjugation, abuse, cruelty, persecution, extraction, exploitation, oppression), and we reach for a sledgehammer to break through that savage wall, shoulder to shoulder with others in an effort to prevail over unfreedom. Fred Moten says that freedom dreams were born in the dark and deadly hold of a slave ship. And Henry David Thoreau, speaking to his friend Emerson from a jail cell, famously said that prison was “the only house in a slave State in which a free man can abide with honor.” In prison, yet somehow free. Identifying and naming injustice, organizing and agitating against it in the company of your chosen family, uniting in love in order to breach barricades and overcome barriers—that’s where freedom explodes onto the scene and comes to life as three-dimensional, vivid, trembling, and real.

Frederick Douglass describes a moment when he refused to allow himself to be beaten by his master’s son and, risking death, fought back. Without any assurances of success, Douglass battled the man to a standoff and defended himself successfully, intentionally refraining from the sweet temptation to beat his attacker to a pulp. Amazingly, Douglass was not punished; perhaps the young man felt humiliated and wanted to simply walk away. In any case, when he reflected on the encounter later, Douglass wrote, “I was nothing before; I was a man now. . . . After resisting him, I felt as I had never felt before. It was resurrection. . . . I had reached the point where I was not afraid to die. This spirit made me a freeman in fact. When a slave cannot be flogged, he is more than half free.”

Douglass had expressed himself openly, fully, and authentically; he had removed the servile and affable mask of compliance by fighting back. He had openly named unfreedom, resisted it, and felt suddenly resurrected—exhilarated, intoxicated, energized. Although still enslaved, Douglass had tasted freedom. Freedom in action. That’s a clear statement of the paradox, the basic contradiction, and the mystery: the “freedom” of sitting on the couch smoking a joint (don’t get me wrong, that’s not a bad thing in itself) is an anemic illusion next to the radiant freedom of punching your master in the nose.

There’s a scene in Stanley Nelson’s brilliant 2015 documentary film, The Black Panther Party: Vanguard of the Revolution, that knocked me off my chair when my wife Bernardine, my brother Rick, and I first saw it and it’s stayed with me ever since. Nelson interviewed a few Panthers—Gil Parker, Muhammad Mubarak, Roland Freeman, and Wayne Pharr—who had survived a murderous assault on the Panther headquarters by the Los Angeles police in 1970. The Panthers described what it was like to be under the full brunt of state violence, trading gunshots with the police for hours and suffering multiple wounds. They were fairly certain that they were all going to die. Then Wayne Pharr surprised Nelson, saying: “I felt free. I felt absolutely free. I was a free Negro. I was making my own rules. You couldn’t get in and I couldn’t get out.” But for those few hours, according to Pharr, “I was a free Negro.” There were no assurances that the Panthers would win, of course, nor that they would move the needle forward even a notch in the centuries-old struggle for Black liberation. There was no certainty that anyone would walk away from the police assault alive. Still, Wayne Pharr claims that for those few hours he felt free.

Wayne Pharr had joined the Panthers to act against white supremacist structures and practices that he’d concluded held him back or pushed him down as a human being—-the police as a brutalizing occupation force in particular. These were injustices to oppose because they created concrete barriers to his and his people’s fulfillment. By naming them as obstacles, he focused attention on them as things to defy and defeat, to live beyond into an imagined and more humane future. Joining the Panthers was acting in freedom, and, arm in arm with others, he was taking on the responsibility of abolishing the offenses—reinventing himself, and now naming himself as an agent of liberation. Choosing with others to be a freedom fighter and acting on that choice, he found some notable measure of self-determination: “I was a free Negro.”

When speaking of her unique perspective on freedom, the philosopher Maxine Greene evokes the memory of Rene Char, a poet and a member of the Resistance during the German occupation of France in the 1940s. Char and his comrades were unwilling to live peacefully in a world that offended their sense of justice and disrupted their lives, so they refused to submit—they chose instead to build an illegal underground organization. Good for them. And, just as with Wayne Pharr and his comrades, just as with Frederick Douglass, their refusal contained no promise of success. Still, risking their lives to challenge the catastrophe unfolding before their eyes felt to them like the only way they could live fully and freely and was, therefore, the correct and urgent thing to do. Acting against invasion and occupation, against fascism, pointed to the possibility of change and announced to any who would look or listen that another world was possible. In the most difficult and dire conditions—Nazis in control, troops marching overhead, danger in every direction—Rene Char described being visited by an “apparition of freedom.” Like Frederick Douglass and Wayne Pharr, Char felt free in spite of, or because of, the precariousness all around. He felt free because he refused unfreedom in action.

“At every meal we eat together,” Char said, “freedom is invited to sit down. The chair remains vacant, but the place is set.” Indeed, they set a place for freedom freedom by taking three small but mighty steps: naming the unfreedom that was maiming and killing them; conjuring with their imaginations a more just and humane world up ahead, a world that could be or should be, but was not yet; and standing up collectively as destroyers of the old, and, therefore, harbingers of the new. Abolitionists. They would make themselves into new women and new men—the necessary creators of a new society.

The specter of freedom can appear in contexts that are either decidedly nonviolent or overtly violent, indicating that the bright line between violence and nonviolence is in fact a wobbly line, largely mythological. Whenever the words “violence” or “nonviolence” land in the mouths of the powerful—any member of the ruling class, the one percent, or the chattering political class—beware their insincerity, their virtue-signaling, their deception and naked hypocrisy.

There was a time, not so long ago, when slavery was the normal and legal state of things. When Nat Turner or Gabriel Prosser or Denmark Vesey or hundreds of other freedom fighters led uprisings for freedom, they were immediately labeled violent savages. To not notice the crushing violence inherent to and congealed within the slave/master relationship is myopic at best; to see the slaves suddenly rise up, and to call that out—with righteous indignation—as violence is willful blindness. Remember Harriet Tubman with that explosive pistol in her pocket.

I recently met in an Illinois state prison a street-level drug dealer from Chicago who got into a beef with a rival, pulled a gun, and stole some money from him and is now doing ten years—a violent crime, no doubt about it. But I couldn’t help thinking about the notorious Sackler family, billionaire owners of Purdue Pharma, who created the opioid crisis by knowingly unleashing and promoting the drug OxyContin, killing close to half a million people and destroying thousands of communities. Purdue Pharma pled guilty and forfeited $225 million—chump change for them, and there were no criminal charges against the Sacklers. Why? Because they’re all “nonviolent” lawbreakers. I also wondered how that drug dealer might have fared if he’d had a million-dollar legal defense team.

The “good people” are all nonviolent, we’re told by the overlords (without a hint of irony) because violence is ineffective, counterproductive, and always unacceptable. Violence is immoral. But look a little closer at the people trumpeting those echoing slogans—the prosperous and the powerful—and note that they are oozing false virtue, throwing sand in everyone’s eyes, dripping with blood and hiding the evidence, all of them. It was the LAPD who initiated the attack on the Panther office, but, according to the police spokesman, that’s because the Panthers were violent; the Chicago police drugged and then assassinated Panther leader Fred Hampton in his bed in 1970, but the police were portrayed for years as acting in self-defense. If they really believed that violence was ineffective, unacceptable, and immoral, then they wouldn’t have murdered Fred Hampton, wouldn’t have assassinated Patrice Lumumba or overthrown the elected government of Chile or invaded and occupied Vietnam, wouldn’t be armed to the teeth themselves, unleashing their legions everywhere in the world, creating a militarized, carceral state at home, and nourishing a hyper-aggressive war culture. No, their opposition to “violence” is super-selective—“We can be as violent as we please, but the rest of you must stand down.” More honestly, they could simply say that they want a monopoly on violence for themselves, obedience and compliance from everyone else. Violence is, as H. Rap Brown from SNCC famously said decades ago, as American as cherry pie.

Nonviolence to the powerful means nothing more than passivity, conformity, and acquiescence. When they say “Be nonviolent,” they are not encouraging fierce labor stoppages or militant direct actions. They are not saluting the militants of Extinction Rebellion, Earth First!, or United Nurses, nor the Palestinian strategy of Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions—all nonviolent initiatives. No, they mean “Sit down and shut up.”

More than fifty years ago, Martin Luther King Jr., refusing to condemn participants in the Watts rebellion, called the US government “the greatest purveyor of violence on earth.” He was right, of course, and that judgment holds true: the US not only ranks number one in military spending worldwide; it’s also the number-one global arms dealer, a super-spreader of high-tech killing machines, as well as handguns and low-end murderous weapons.

But bullets and bombs aren’t the only ways to kill people. Bad hospitals and a predatory health-care system also kill people. Government-sponsored enclosures—ghettos—also kill people. Forgotten communities and collapsing buildings kill people. Decomposing schools and brainwashing curriculums kill people. The unhoused have a life expectancy thirty years less than the general population. Thirty years! Violent deaths, quietly executed.

The nonviolence of peace and freedom activists like Martin Luther King Jr., Dorothy Day, David Dellinger, or Thich Nhat Hanh was not passive but, rather, aggressive and defiant. Their nonviolence confronted and exposed illegitimate state violence with the moral right of the people to be treated as fully human. And, of course, in the US South, many of the freedom organizers and civil rights workers by day were protected by armed local community people by night. SNCC leader Charlie Cobb wrote a smart and beautiful book about this contradiction appropriately called This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed: How Guns Made the Civil Rights Movement Possible.

Nonviolence can be a brilliant and creative tactic in the hands of the oppressed, and violence is indeed abhorrent, but these categories are neither neat nor fixed.

In our given world, the world as such, we’re challenged to set a place at the table for freedom. We open our eyes wide, shake ourselves awake, and look closely at our real conditions: the beauty, the joy, and the ecstasy in every direction, as well as the undeserved pain and the

unnecessary suffering. We open a space for freedom—we set a place at the table—when we identify the unfreedoms pressing us down and endangering our lives and our human dignity, imagine a better world for all, and act to resist and someday abolish unfreedom.

✶✶✶✶

Bill Ayers is a community activist, an educator, and host of the podcast Under the Tree: A Seminar on Freedom. He has written extensively about social justice and democracy, education and the cultural contexts of schooling, and teaching as an essentially intellectual, ethical, and political enterprise. His books include A Kind and Just Parent, Fugitive Days: A Memoir, and Public Enemy: Confessions of an American Dissident.

✶

Whenever possible, we link book titles to Bookshop, an independent bookselling site. As a Bookshop affiliate, Another Chicago Magazine earns a small percentage from qualifying purchases.