I am afraid to talk about money.

✶

One of my earliest memories is of my father coming into my room in the dark and emptying my ceramic piggy bank into the palm of his hand. “Dad, what are you doing?” I whispered sleepily. It was like catching Santa Claus or the tooth fairy; only my dad was taking my money, not leaving some. “I need it for gas,” he said and walked out.

It seemed everyone loaned my dad money at one time or another: Dad’s brothers, Dad’s parents, Mom’s parents, and even anonymous donors. I recall these miracles, my parents crying on their bed, holding a check in their hands. “We don’t know who sent it,” Dad would say. “God always provides.”

I grew up in Southern California with my parents and three sisters. My dad worked as a construction superintendent, and my mom was a homemaker until I went to high school. After that, she began working as a lunch lady at the local elementary school. The terms working class or middle class meant little to me. I only knew that my parents’ financial situation was stressful and often embarrassed me. I thought our Chevy station wagon looked old, that my mom should shop at Nordstrom instead of Ross, and that it would be nice to buy actual candy at the movies every once in a while rather than sneak in bags of pretzels and apples. We weren’t poor; we owned a home, had two cars, and a stocked pantry, but we never had enough money and were perpetually losing the house.

Who knew where the money went?

Though my father never said it out loud, wealthy people were the enemy. Rich people, like his older brother and various cousins, had it easy, and this easiness made them less grateful, less hardworking, and maybe even less human. Rich people lived in two-story houses, mansions, and castles. They had too much plush carpet to know what the cold, hard earth felt like.

Little did I know then that my father was the black sheep of his family, not because he didn’t have money but because he was spending all of it on drugs.

When I was thirteen, everyone’s worst fears about my father came true when he took a dangerous dose of opioids and crashed our car with my mom, three sisters, and me inside. It was 2002; I was thirteen, and my mom was forty-two. Though all of us were hurt, it was a miracle my mom survived. She suffered a traumatic brain injury that took over a year to heal. Even then, the doctors warned she might be living on borrowed time.

My dad was in and out of work for years after that, and in 2011, the year of my college graduation, and nine years after the accident, my parents finally lost our house. As if sensing the end of an era, my mom’s brain injury began to resurface in the form of early-onset dementia. My parents moved into my grandparents’ two-car garage, which my dad converted into a one-room studio. Their time was supposed to be temporary, but knowing my dad and his history, I suspected otherwise.

✶

In 2007, I chose to pursue higher education. I went to the only college I ever visited, a Christian liberal arts university in San Diego that my aunt went to when I was young. Save for a $5,000 low-income scholarship, I took out student loans to pay the exorbitant tuition. I did so under the ill-advised guidance of family members who had never gone to college, who reassured me that everyone my age took out loans. Like many others of my generation, by the time I graduated, my student debt was paralyzing. It totaled more than $100,000.

It wasn’t until my first loan payment was due that I realized what I’d done. It was the peak of the recession, and no one could get a job. I shared a one-bedroom apartment on the edge of San Diego’s 805 freeway with my two younger sisters, Samantha, then nineteen, and Bethany, sixteen. Of the three of us, I was the only one with a college degree, a BA in social work. It was a degree that–my long-time pre-med roommate’s parents liked to remind me–would never earn me a lucrative salary. I knew social work didn’t pay well, but I wanted to help people, and unlike my true loves, theater and creative writing, it seemed a practical career path. I loved kids and figured I’d find a place helping underserved youth.

That first summer after graduation, I spent months interviewing for jobs at various nonprofits and after-school programs, with little luck. Finally, I landed a cashier position at a local Panera Bread. Samantha, Bethany, and my boyfriend Jeff, also desperate for work, were employed there that same week.

Those were dark days, days spent riding my bike several miles to a bus stop before the sun rose, hauling leftover bagels in a trash bag on the ride back home to stretch our food budget, and hearing my manager bad-mouth Bethany, who was in the early stages of addiction. But the job and that time were temporary, and I hesitated to complain. Who doesn’t struggle in their twenties? Spending time as a poor college student, or poor college graduate (in white, middle-class circles, at any rate), is an American rite of passage considered to be almost precious. At least I had a home, a job, and a bike. I had come to accept my debt as a beast that would shadow every moment of my waking life.

✶

The truth is, I start with this story because I want to remain relatable. In this story, I am another run-of-the-mill millennial saddled with student debt. In this story, I am not yet a millionaire.

✶

This is the other story:

I couldn’t begin to imagine why, on a spring afternoon, my boyfriend’s parents were in town and texted me that they wanted to meet me alone. I had recently quit my position at Panera Bread and was working three jobs: as a nanny, a receptionist for a yacht broker, and a late-night hostess at a bar downtown. I was still living with my sisters and now I was borrowing Jeff’s truck to get to and from job to job. Jeff had work sorting mushrooms at a produce-distributing facility just a few trolley stops from his apartment. We had been dating for over two years, and there was mutual affection between his parents and me. Still, I was nervous as I knocked on the door of their bayside hotel. Why did they want to meet me alone?

Jeff’s dad opened the door and wrapped me in a big hug. His mom responded in kind, kissing my cheek.

“Come, sit down,” she said.

I took a seat on the couch, and Jeff’s dad brought me a glass of water.

“Don’t worry,” his mom said. “Nothing’s wrong.”

“Oh good,” I replied.

“Jeff told us about your student loans–” his dad began.

“Oh?” I could feel my cheeks flushing. My loans? Had I financially burdened their son by association? Did they think I was irresponsible for taking out so much money?

His mom quickly interrupted. “We have been thinking about this for some time…we want to pay them off for you. Whether you end up with Jeff or not, we love you.”

I was stunned. Sitting there staring at them, I could not believe their power—that they could make the debt, the beast, vanish in the blink of an eye. For them, it was merely a drop in the bucket. The imbalance felt absurd. Before I could even speak, I dissolved into tears.

“This is too much,” I said.

“We love you, Alissa,” his mom said. “Let us do this.”

And just like that, my $100,000 debt disappeared.

✶

A year into our marriage, Jeff’s parents sat us down, this time under an oak tree at Huntington Gardens in Pasadena. Jeff and I were twenty-six. For months we had been scraping by, working multiple jobs and sharing a two-bedroom granny flat with two college friends, another young, married couple. My in-laws were in town from Sacramento, visiting us for a long weekend. They prefaced our Saturday trip to the gardens by telling Jeff ahead of time that there was something they wanted to discuss. I thought it was going to be about our faith. Jeff and I had long since drifted away from our Christian roots, and we knew they were concerned. As the four of us sat down, I thought of ways to say, “I am not a Christian anymore” without breaking their hearts. I didn’t want to disappoint them. And though that conversation came later, this one was not that.

“Jeff has a trust fund,” my father-in-law began, “and through a series of good deals and the Lord’s blessing, the trusts have grown quite…substantially.”

Jeff’s parents went on to explain monthly distributions and investments and tax brackets — money-speak that sailed straight over my head. I sat there, staring at a bush of camellias, thinking, Am I rich? Am I one of those rich people? Sure, I knew my in-laws had money. They took several vacations a year and had paid off my student loans, for heaven’s sake. Maybe it was naive of me to be surprised. But I had never even heard of a trust fund or imagined inheriting anything outside of, maybe, my grandma’s wedding ring.

Jeff didn’t know about the trust. He knew he might inherit money one day, but never anytime soon and never this much. His parents wanted to wait until he was married and employed before informing him of the news.

His dad reminded us that it was enough money so that we could do something like start a business or pursue a graduate degree, but not enough to enable us to do nothing. In other words, the money wasn’t there to live on, and besides, we didn’t want to live off it.

We kept our jobs and tried to pretend the money didn’t exist.

In those early years with the trust fund, whenever Jeff and I considered a big purchase — a vacation, a North Face jacket, a new couch — we first playacted as though we should budget for it, like responsible adults. Then, we would look at our bank account overflowing with monthly trust distributions, and stare at each other mouths stretched, eyes wide, a full-faced yikes, like we were complicit in some sort of shameful secret. We were still living in disbelief.

✶

Those first few years with the money, Jeff and I offered to pay for everything we did with my family. We took my parents to Germany one Christmas to visit my older sister. My mom had never been out of the country. We helped with Dad’s car payments, paid for my sister Bethany’s ninety-day rehab, and covered dinner every time we went out. But after a while, covering the family bills started to feel uncomfortable, almost inconsiderate, as if I were belittling my family by assuming they couldn’t or wouldn’t want to contribute. And yet, there would always be something: a car problem, a medical bill, gas money. After paying for my dad’s Naltrexone implant in 2015—this is a drug used to help detox people off opioids ($8,000 not covered by insurance)—I vowed it would be the last time I intervened.

Detach with love, Al-Anon encouraged. Detach my bank account with love.

✶

It had been six years since I’d given my dad any money when one morning, he sent me an urgent text:

I need to pay my car insurance today. Need to pay all my bills actually. I am down to $14.

Fun week ahead.

How much do you need me to transfer?

It is somewhere around 5000. $4600 should be good.

Was it possible Dad was really down to $14? He often exaggerated, but this time it was different. There was my mom to think about.

It was the spring of 2021, and my mother’s cognitive decline was becoming more and more apparent. Her needs were growing beyond what Dad and my eighty-year-old grandparents could handle. Dad worked full time as a solar panel technician, and neither my sisters nor I lived nearby. Mom clearly needed round-the-clock care, and Jeff and I were paying. We both had agreed that we would do whatever we could to make my mom’s life more comfortable.

We had signed up for automatic withdrawals with the care company, but the setup went wrong. The first month, it had come out of Dad’s account instead. Hence, his urgent text.

An hour later, I found myself behind the plexiglass window at my local Wells Fargo, feeling, as always, a stark and uneven distribution of privacy. While the bank tellers remained safely behind bulletproof glass, their voices gently muffled, we, the patrons, stood in the open air, in library-like silence, bereft of confidentiality or anonymity while discussing the unspeakable.

That morning, I could hear everything.

“Twenty-five hundred dollars in twenties, please,” said the man to my right. He looked like one of my old Ken dolls: proportionate, clean-shaven, white.

Twenty-five hundred dollars. So much cash. Twenties for his business trip? To tip drivers, hookers, to cover drinks?

To my left, a young man with a silver pocket chain and red Vans deposited a check, which he slipped in the metal slot like a patron at a ticket window. I remember depositing checks like that when I worked at Panera, before mobile or direct deposit. He seemed too young for such old-fashioned banking.

“All set,” the cashier said.

“Cha-ching!” the boy trilled as he bounced off.

At a bank, you heard it all: exact dollars, exact change.

“What can I help you with?” asked the young bank teller, pulling up my account, her violet acrylic nails clicking on her keyboard.

“I need to transfer money to my dad. He also banks with Wells Fargo.”

“Is he an account holder on your account?”

“No.”

The idea was laughable. My dad, an account holder on my account.

“No, he is not an account holder,” I told the banker.

At this point, an older, gently-balding bank teller stepped in to help. I had anticipated this, a slight complication. It had been several years since I’d sent money to family members. Now, the man and the woman were staring at my account on their computer screen. I knew what they saw. It was a large number. A number that no longer shocked me but probably should.

“We can’t actually transfer money to another account,” he said. “Did you log on and try to transfer through—”

“Zelle? Yeah. It’s more than $500.”

“Oh, okay. How much did you want to send?”

Standing there in the stifling silence, I felt my privacy slipping. Was I supposed to discuss this out loud?

“Forty-six hundred,” I said quietly.

“Four thousand and six hundred dollars?”

“Yes.”

Was $4,600 a lot of money to send to someone? Since marrying into millions, my gauge had become distorted. I hated myself for many a thoughtless, privileged remark, for assuming that $20 was cheap for a bottle of wine, for suggesting we split the bill even though someone purposely hadn’t ordered a cocktail, for suggesting our tour guide in Vietnam visit us if he was ever in California. “I have never left this city,” he laughed. God. I wanted to slap myself across the face.

“Do you have checks with you?” the male teller asked.

“No.”

“That’s OK,” he said, taking over the computer.

The woman with the nails scooted over and leaned against the counter like this might take a while. She twirled a pen in her hand, then gripped it like a butcher knife, hovering it over the man’s left hand.

“When your hand is like that, I just want to stab it,” she said.

She laughed as he pulled his hand away. There was so much I didn’t know about them and so much they must have assumed about me.

“Here’s what we can do. We can print a check for you, have you fill it out here, and then deposit it into your dad’s account.”

“Right now?”

“Yes.”

“Is it instantaneous? Like, can he access the funds right away?”

“Within twenty-four hours,” the man said.

“Okay, let’s do that.”

I was grateful things were working out.

Worst case, I could make the eight-minute walk home and grab a checkbook or call my dad and tell him it would have to wait for tomorrow.

The female bank teller had taken back over after walking away to print a check.

“Can I ask how old you are?” she said.

“Thirty-two,” I replied, thrown by such a personal question.

“I just don’t see many people with that much in their savings account.”

“Oh—yeah. We don’t usually have that much,” I slobbered. Did I look like a teenager? Maybe it was my Levi overalls. Was what she was asking me even appropriate?

I mumbled something about selling a house, which was sort of true. I didn’t consider telling her, “That’s none of your business.” I felt exposed and judged. I knew the number on her screen, a long-tailed set of digits that meant something about me—although what?

If I am being honest, I used to take pride in the suffering that not having money afforded, as if struggling financially added depth to my personhood. I thumbed my nose at rich people—the college kids who didn’t have to work, my cousins who got to order soda when they ate out. I thought being poor made you more empathetic, authentic, and down-to-earth.

Jeff and I never formally decided if we should tell my dad about the trust fund. Then, one afternoon, about a year into the trust, I broke the news to Dad over the phone. I am not sure how it came up. I was driven by a childish need for attention or approval (or both), and the secret gushed out of me. I can’t remember what Dad said or how he reacted. I know that several days later, he called to confess that he was jealous of me. He said it just like that, without even an edge of remorse, and I knew I was catching him at his worst. For all his self-centeredness, he wasn’t one to punish me, which is what this felt like. I told him I was sorry, hung up, and cried. We never talked about it directly ever again.

On the walk to the bank that morning, I had wondered what an average savings account looked like. How outside the norm was I? Perhaps the bank teller was the one to ask.

Her asking my age flustered me, but she seemed unfazed. If anything, she felt even more inclined to break the professional facade.

“This one time,” she whispered, leaning towards the plexiglass, “this guy came in here complaining about a $100 overdraft fee, and he was like, ‘This is messed up! I want you to read off all my charges.’ This was before these glass walls, and so, like, everyone could hear us. He was talking loud, you know, and I was like, ‘Sir, why don’t you read through the charges here.’”

She pointed her finger and pressed it against an imaginary piece of paper on the counter.

“I passed him a printout of his statement, and he said, ‘No, I want to hear you read it!’”

I made a shocked face to indicate that I was listening, although my expression was more due to her candidness.

“He was yelling at me, saying, ‘This is all your mistake!’ And I said, ‘Sir, are you sure you want me to read this out loud?’ and he said yes. So I read them.”

Her eyes grew wide, and her voice even softer.

“He had about fifty charges made to OnlyFans. OnlyFans! So embarrassing, right?”

“You would think that would be embarrassing,” I said.

She straightened up and swept her bangs away from her face as if shaking off the memory.

“Anyway,” she said, hands posed above her keyboard, “what is your father’s birthday?”

“February 22, 1960,” I said. I was imagining telling Jeff about this later.

“Great. I got his account pulled up.”

“You know,” she says, “You can add your dad to your account if you expect frequent transfers, but it would mean he’d have access to the account.”

“Yeah, no. I don’t want that.”

“Yeah, probably not.”

“I would like access to his account,” I said with a laugh.

“Right?” she said.

With how many people was there such transparency?

I could only guess at her narrative. The two accounts, my father’s and mine, nestled up to one another on her screen, one with $14 and the other with thousands. I could see her wheels spinning. What was up with this father? What did I do for a living? Had I married into money? There were some things she knew, but a lot she didn’t. She knew I was wealthy, and my father was not. She knew of my distrust and his dependence.

I wanted to defend us both—to tell her that my mother was dying, that my father, despite his many faults, was doing the best he could, and that I hadn’t done anything at all for the money. It was pure dumb luck. I wanted to tell her that money didn’t buy happiness, even though I knew it made life easier. Maybe easier was happiness.

She made the transfer.

“Okay, he has $2,200 available,” she said.

“Okay.”

“That’s it. You are all good.”

“Thank you.”

I was too eager to leave to have her clarify what she meant. $2,200 available of the $4,600 I sent? Or did he already have that much in his account? Either way, it wasn’t a lot, and I knew, too, that the $14 was likely an exaggeration.

The $4,600 transfer was not for Dad, I told myself. I was sending it to Mom.

✶

Six years earlier, in December 2015, I had bought my mom a heavy woven sweater from Anthropologie. It cost $250. At twenty-seven, I had never spent so much money on her before, and I am ashamed to admit that it was hard for me to do. For one thing, I loved the sweater and debated keeping it for myself. For another, Mom’s memory was slipping. I could picture the sweater lost and forgotten in the back of her closet.

That was the first Christmas of my dad’s sobriety, and no one had wanted to accept that Mom’s fourteen-year-old brain injury was showing new signs of activity. The timing of Dad’s recovery and Mom’s neurological decline reminded me that life was anything but fair. I suppose we were all in denial: my dad, most of all. My family was eager to put the past (and Dad’s unforgivable mistake) behind them. I didn’t want to accept that I was losing my mother and that, to some extent, it was my dad’s fault.

That Christmas, after nearly thirty-five years with my dad, years spent sick with worry (Will he keep his job this time? Will he try to kill himself again? Will he ever get better?), my mother stopped driving. It was the first of many skills she began to lose.

Friends told me that because of Mom’s condition, she might qualify for some financial support. However, after months of phone calls with county services, including Social Security and Medicare, we learned that because of Mom’s age, she would not qualify for any sort of substantial help, and regular health insurance did not cover long-term care. If she were over 65, she could qualify for Medicare. If she was divorced from my Dad and making less than $17K a year, she could be eligible at an earlier age. But regardless, Medicare would pay only for short-term or limited amounts of care (if anything at all). The most we could hope for was Social Security Disability. A year after sending in her application, Mom qualified for $776 monthly.

Inherited wealth meant we could afford Mom’s care with or without government assistance. But what was the average person supposed to do?

To qualify for Medi-Cal (California’s Medicaid health care system), a family of two must make under $25,268. It was hard to imagine two such people living under a roof at all.

When I asked a county health advocate how anyone afforded home care or nursing homes, she said many people took out long-term care insurance policies earlier in life to cover future care. I was baffled that anyone was so prepared. But, then again, wasn’t this sort of personal responsibility the linchpin of our capitalist nation?

In a culture where individual responsibility was paramount, I wondered where my mother went wrong.

- She should have left her alcoholic husband. It’s her fault she ended up getting hurt.

- She should have worked full-time, saved for retirement, and taken out a long-term care policy, all while preserving the great American dream of being a stay-at-home mother devoted to raising her four kids.

- She shouldn’t have had kids if she couldn’t afford them. Instead, she should have worked as many jobs as needed, parsing out the money in various savings accounts so, at the end of her life, she could live under the careful watch of a caregiver and die after a long life spent financing her long life.

Only a brutal society would regard my mom’s fate as a natural consequence. My mother loved my father, for better or worse. They never figured out the money thing. Maybe I wouldn’t have either. I just happened to marry into it.

Inheriting money turned the bootstraps analogy on its head. The idea of working hard and earning it did not pertain. Jeff and I did nothing, and yet we were millionaires. I was once quick to say that Jeff’s dad did something: he earned this money that we now have. But “earning” is a subjective term. The hardest workers in our society are often the least compensated: the teachers, the social workers, the caretakers. Most of my father-in-law’s money was made through luck, buying at the right time, and selling at the right time, and it would have been nearly impossible without the levels of privilege from which he started in the first place as a white man in America.

“I guess some people have to quit their jobs to care for their family members,” I told Jeff one night. “Should I be doing that?”

I used to judge people who put their parents in nursing homes. I vowed I would give up everything to care for my parents, for Mom at least. But back then, I didn’t know the horrendous realities of dementia, of afternoons trying to placate my sobbing, terrified mother, of finding feces in her dresser drawer. I didn’t know about the way she would put herself and others in danger, like the time she smashed a ceramic plate over my dad’s head while he was sleeping or nearly jumped out of the car while he was driving. Besides being difficult to manage, it was heartbreaking and terrifying to watch.

And what did it mean to care for my parents? Both Mom and Dad? My father, a long-time addict, broke my trust again and again. What did detaching with love really mean?

To say I was grateful for the money is an understatement. It not only allowed for my Mom’s care, but it buffered me from the darkest days of her disease. Selfishly, it allowed me space to live my own life.

Nothing about it felt fair.

✶

In the end, Jeff and I only paid for my mother’s care for four months before she passed away. After that, our contribution shut off like a faucet.

The week of my mom’s passing, I received urgent texts from my Nana and my aunt Patty. They wanted to remind me to man the sails, bolster the troops, and keep my guard up; my dad would come asking me for money. I supposed I couldn’t blame them. He had been asking them for money since long before I was born. I couldn’t help but feel angry, though. I never asked for their advice, and my mom had just died—my mother and my father’s wife, I wanted to remind them. The timing felt insensitive, and was it possible that my dad had changed? How long would he be held hostage by his past behavior? How long are any of us?

A week later, my grandparents asked my dad to move out of their garage-turned-studio. It was a request long overdue.

Dad planned to move from Moreno Valley to San Diego to be close to my sister Samantha and me, but he was doubtful he would find a place he could afford. It had been two decades since he had rented or purchased a place, and he was unfamiliar with Craigslist, Zillow, or any of the other internet-based property-finding sites. I insisted on helping him look.

Filtering apartments within Dad’s budget presented very few options, and the more I scrolled through Zillow, the guiltier I felt. Were I to help Dad with rent, he could get a place much bigger than the 300-square-foot studio apartments he could now afford. Then again, what could he afford? He knew about my money, but I didn’t know much about his. Our transparency only flowed in one direction. He never told me how much he made, only that it was never enough. He still worked full time and often overtime at a solar power company. I didn’t know what to believe; it was none of my business. Or did helping him entitle me to this information?

One afternoon, after weeks of texting listings back and forth, Dad came over to look at places together. We sat at my dining room table and scrolled through the Zillow listings.

“I just can’t afford anything,” Dad said, defeated. “I don’t know how I will make this work.”

“What can you afford? What are your current expenses?” I asked.

Dad leaned back in his chair and shook his head, clearly irritated that he had to do this at all.

“There’s my health insurance, that’s around $800. And car insurance, car payment, cell phone, and then yours and Ashley’s student loans.”

“What student loans?”

“I have almost seventy grand in student loans.”

“What? Jeff’s parents paid mine off.”

“Not all of them.”

“Dad, there’s no way there’s that much. What are they, parent-plus loans?”

“Yep.”

It was true that my Dad had taken out a loan for one year of my schooling—or was it half of a year’s tuition? I can’t remember. And it was true that he had done the same for my sister Ashley, so it’s likely he did owe that much with the ever-accruing interest. Was this his way of asking me to pay them off for him?

What I didn’t say to Dad had been his choice to take out those loans just like it had been mine.

I understood a forty-something-year-old, longtime addict taking out a loan was not the same thing as an inexperienced eighteen-year-old doing it. But by what measure were we worthy of absolution?

What really was Dad responsible for? My mom’s brain damage and her early death? Hadn’t he been punished enough without the additional burden of financial strain?

Sometimes, what is right is obvious, like paying for my mother’s care. More often, it isn’t.

In the end, Dad found a two-bedroom apartment with a twenty-seven-year-old roommate, a guy he worked with named Ricky. Ricky didn’t seem to mind Dad decorating the place with his and Mom’s old things—the rooster plate collection in the kitchen, the mallard ducks on the fireplace mantel, and the two stuffed bears dressed in period clothing. Dad was stoked to live only eight miles away from me, plus the place had a balcony where he could store his surfboard. He began signing off every text and phone call with his new mantra, “best life ever.” He stopped bringing up the student loans.

✶

For years, I’ve received the same Venmo alert: I’ve requested $78 from Patrick. Do I want to remind him? Long ago, when I sent this request to my dad, I was trying something new: accountability. I had coddled him long enough. I assumed, perhaps falsely, that he never had money. The $78 was for Dad and Mom’s portion of a Christmas dinner at Riverside’s Mission Inn that we shared with my extended family in 2019. That evening, thirty of us split the bill. To simplify it, I offered up my debit card for my nuclear family. It was easy to ask for a reimbursement from my older sister Ashley, whose husband worked for Volkswagen. It was difficult to ask it of my sister Sam who was starting up a bakery in her home kitchen and worked so damn hard. I didn’t bother to request the money from my youngest sister, Beth, who had just gotten out of rehab. The hardest of all was asking Dad. Ultimately, Ashley and I covered Beth’s portion and paid half of Sam’s. We didn’t offer any such help to Dad, and he never paid me back.

Asking for the money more than three years later would be ridiculous. Hadn’t my parents fed me for eighteen years? What was $78 to me, anyhow? Why not just cancel the Venmo request? Clear the queue. What was I waiting for?

I didn’t want to be an enabler. But maybe worse, I didn’t want to be an ungenerous millionaire.

A couple of weeks before Christmas 2022, I finally canceled the Venmo request. I wasn’t going to ask Dad for the money. I didn’t want to. Later that week, Dad said he got me a gift. Something framed, he said, and I figured it was likely a piece of art by his friend who watercolors on the boardwalk at Ocean Beach. I was right. On Christmas morning I opened a four-by-six painting of a sailboat on the harbor. Dad pointed out the signature in the corner and reminded me that no two of the artist’s paintings were alike. I loved the painting, and I loved Dad’s delight in giving it to me.

I couldn’t remember the last time my father gave me, or anyone else in my family, a present. When my son was first born, nothing. Even on my son’s first birthday, nada. It wasn’t about the money, I don’t think. Rather, Dad had wanted to find the perfect gift, a gift to cover a multitude of mistakes and missed opportunities, and never could.

✶✶✶✶

Alissa Bird is the former managing editor for the UCR literary journal, The Coachella Review. Her work has appeared in The Coachella Review, Kelp Journal, and Reservoir Road Literary Review. She lives in San Diego.

✶

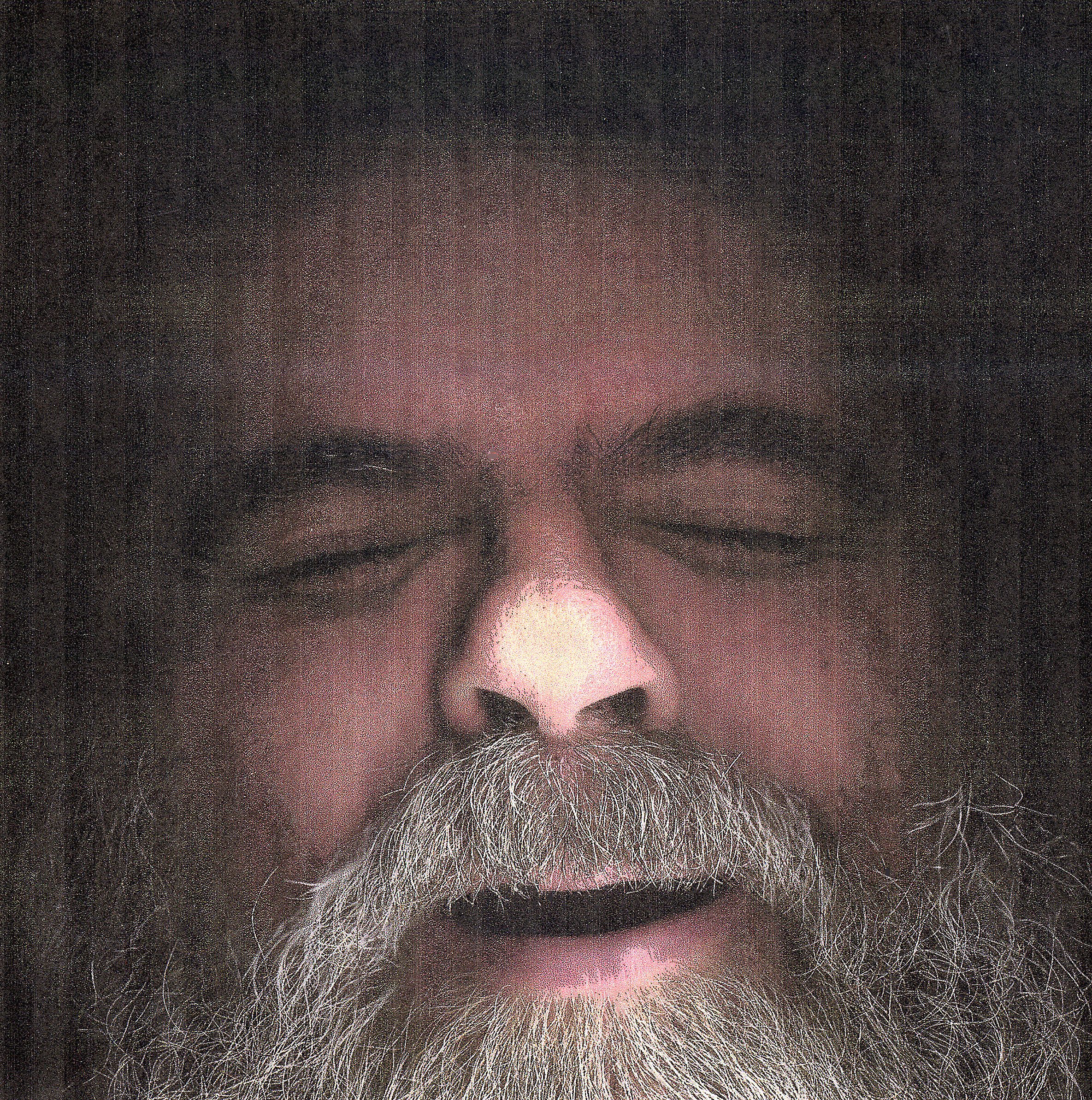

Originally from New York City, Robert Bharda has resided in the Pacific Northwest where for 40 years he has specialized in vintage photographica as a profession, everything from daguerreotypes to polaroids. His digital ‘Quantisms’ originate from templates composed of all organic materials (mushrooms, leaves, flowers, seashells, et al) and seek to release dynamic motion from fractal potential. His illustrations/artwork/photography have appeared in scores of publications, including: Naugatuck River Review, Catamaran, Cirque, Northwest Review, Blue Five, Superstition and Adirondack Review. He is also a writer of poetry, fiction, critical reviews published in one hundred plus journals and anthologies.