We continue our examination of literary fame, which we began on Tuesday. What follows is an edited transcript of a discussion at the Association of Writers & Writing Programs conference on March 9, 2023. Zack Rogow moderated the panel “Literary Fame: Should We Strive For It? Should We Care About It?” that included Dion O’Reilly and Richard Blanco. Panelist Cornelius Eady could not be present, but joined via video with an essay and poem. Let us know on social media (Meta, X, Tiktok) what you think. How much does fame motivate or discourage you?

Intern Olivia Shay transcribed the recording.

—S.L. Wisenberg, ACM editor

✶

Zack Rogow: Does literary fame play a role in your quest as a writer and if so, does it play a positive role, or a negative one? And how does it affect you as a writer?

Dion O’Reilly: I think there are some ways that fame can be positive because it makes me want to submit. And I try to look at my poems and listen to them and ask them, “Do you want to be submitted? Do you want to go out in the world?” The impetus doesn’t necessarily come from, “Oh, I want to be famous,” but does my poem want to be famous? I’m inspired to look at the literary landscape to look at the journals. And you know, I try to do a little Match.com: Do they want my poem? And does my poem want them? The way that fame is bad is that it can be demoralizing if that is where the focus is, and it can be paralyzing, and it’s superficial.

Richard Blanco: I go back to my mentor Campbell McGrath. I think it’s only natural and human to want to achieve some kind of fame for your work, but he always said to our class, “Worry about what you have some control over, which is writing the poem, and not when the White House might call.” So I’ve always come back to that. For me, what keeps me writing are those quiet moments when I’m not even Richard Blanco, I’m just this poet immersed in my work.

Then there’s the time to promote your book and to try to get readings and to send out to magazines. I think, as poets, we sometimes we think very little of ourselves. It’s okay to dream big and think big.

Rogow: The desire to publish is, in a way, an opportunity to become your own editor. And in that way, it’s very useful for me.

Could we talk about the way in which fame can be a negative influence in your work as a writer? Do you feel that fame has affected your relationships with your literary peers and made you miss out on some interactions that help you grow as a writer?

O’Reilly: I just want to connect with people on more of a heart level than an “are-you-a-famous-person?” level. And I don’t want to be a social climber. There are famous poets who are wonderful and there are emerging poets who are worth meeting, too.

Blanco: It can be very isolating from your own community of writers to think that only three living poets have served as presidential inauguration poets. You can’t just call a friend and say, “Hey, what’d you do last time for this?” It can be lonely at times. So that’s been a negative thing because there’s this sense that just because you’ve reached some kind of fame, every poem you shit out is going to be amazing and brilliant and you’re like even more scared to publish now. Or the idea that you’ve got to, top yourself in some ways. There’s also the fear of, How long will it last? I spent ten years living the dream as a writer, going around the whole country, traveling seventy percent of my time, but in the back of my mind, I was like, “When is this gonna run out?” So you always think about Plan B as well. It gets harder to write, too; it gets harder to find time to write because you are living as a writer and that means getting on a plane three times a week or whatnot.

The stakes are higher but the fears are the same. Or maybe the fears are even greater? You’re always challenging yourself, asking, “What’s next? What’s the next thing in terms of work and challenging yourself?” To not rest on your laurels, or not rest on writing the same poem over and over again, taking chances. So I think in that way, to be an artist is to always be a part of something that has not been created.

When we look at careers of artists who keep on challenging themselves, despite awards and honors and whatnot—I think those are the careers that I admire in terms of fame and balance.

Rogow: One thing that I’ve noticed is that when a writer receives very major recognition, it’s hard for me to continue to stay open to that writer and enjoy their work. The jealousy gets in the way of appreciating them as an artist. I want to like their work as much as I did before they were more famous than me.

O’Reilly: I really appreciate that honesty.

Blanco: Well, I’ll respond to that. Guess how many MFA programs I’ve been invited to read at? Guess how many. I think maybe two. I don’t know what’s going on.

It’s surprising I’ve read at the USDA, at the FDIC, and fundraisers, all which is one of the fun things about literary fame. You get to be this poetry ambassador to all these crazy places that would never invite a poet because they’ve probably never even heard of a poet. So that’s on the plus side.

O’Reilly: I think that’s a thing, when people get really famous they’re sometimes not cool anymore. You know, like Billy Collins. I think some people don’t like him because he is famous.

When my mind is on fame, which Cornelius mentioned, it’s related to jealousy and ambition. When my mind is in jealousy, and when it’s resenting people, and when I’m not satisfied with myself, it’s just not pleasant. It’s just not fun. It just doesn’t feel good. I can remember thinking to myself, “Okay, if I could just get in the Sun then I will have arrived.” I think the idea that you get somewhere and then you are engraved in stone—that’s just denying the essential ephemeral nature of existence. Do I want to do that?

Rogow: I want to take an informal poll on the topic that Dion just mentioned. So does anyone know who John Cleveland is or was? Raise your hand if you know.

[No hands are raised.]

John Cleveland was the most famous English-language poet in the seventeenth century. He was an extremely popular poet. And we’re a bunch of people who love literature, and we don’t even know his name. So when I first heard about John Cleveland, I thought, “I don’t want to be the John Cleveland of my lifetime. I don’t want to be the person who had that flash in the pan but whose work is not remembered.” And then if you think about Emily Dickinson, she wrote 1800 poems. How many did she publish in her lifetime? How many people knew Emily Dickinson was a great poet in her lifetime? Almost nobody, just her circle of friends. And yet all of us know Emily Dickinson. So it’s better to be like Emily Dickinson than like John Cleveland.

Blanco: “I only read dead people.” I’m just kidding. I think on the flip side a little professional jealousy is fine. I think it makes us think, “Damn, I want to write a poem that good,” and “Damn, maybe my next book may win the Pulitzer Prize.” That’s how I try to approach it when I’m feeling jealous. I always try to turn that little bit of jealousy to “Well, you know, shut up, Richard and sit down and write a good poem.”

O’Reilly: I think all of us have had the experience of reading a really great poem by someone else and thinking, “I can’t do that.” But what I like to do is cut and paste that poem onto a document and just really look at it and ask myself , “What’s my version of this? How would I have done it?” And just let that push me a little more. Consider dharma. From what I understand, dharma is when you ask yourself ask, “What feeds my soul? What makes time stop for me? What moves me toward my bliss such that I just have to do it?” And saying, “How is my dharma related to this poem that I’m so jealous of?”

Rogow: You want to be somebody who’s still talking to the generation that’s coming of age 100 years from now, like Walt Whitman said in “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry.” These are the people he’s speaking to, the people who are living in the future, who are dealing with the problems that we’re just beginning to see emerge, or the challenges, or the excitement.

Blanco: I have one little ritual when I write. I have a three-wick candle. I light one for my literary ancestors. One is my human ancestors, and one is to the little child in me. I always come back to Blake, that the child is the perfect creator. There’s a spiritual element that we don’t talk a lot about in workshops. So, thank you for bringing that up. The ritual settles me down and says, “You know what, I don’t care how many emails I have and who’s calling for what and who the poet laureate is.” Maxine Kumin used to talk about this all the time. It’s as if I’m sitting down to write a poem for the first time, that’s the spiritual practice as well as the writing practice.

Rogow: I’m kind of spiritually challenged. But I do believe that each of us is a different kind of vehicle, a different shape of vehicle, a different flavor of vehicle, but we’re all vehicles for whatever you want to call it—the goddess of literature, the muse. And our work is, more or less, to try to become the best, the most beautiful, the most crazy, the most fitting vehicle for whatever it is that we particularly can channel.

Blanco: Being a vehicle. I think that’s very humbling. As we like to say, once we write a poem, it’s no longer ours.

O’Reilly: I think often of my father and, anyone who’s read my books knows, God knows, he made a lot of mistakes. But he was a real union guy. He was a union organizer. One thing I took from him is the value of being a working person. I’m a working poet, I sit down and I do my work. And sometimes it’s revision, sometimes it’s working on a manuscript, sometimes it’s submitting, and sometimes it’s sitting in that kind of holy place, that sacred portal, and trying to channel whatever it is that makes the poem come through me.

Rogow: Those few moments you get when there is that recognition, whether it’s when you hold the magazine in your hand that has your work in it, and your name is there, and your bio’s in the back—really cherish that moment because it’s going to help you and help sustain you and help increase your own connection to the literary community. If it’s a book that you published, that’s a big thing, you should celebrate that, you should celebrate it more than you gnaw at yourself when something doesn’t get accepted. And if you do that, when your friend says to you, “Oh, you know, I just got published in the American Poetry Review,” then you can be happy with them.

O’Reilly: It’s really hard for me to remember to celebrate. So thanks for mentioning that. I want being a poet to be fun. And so part of that is not looking for famous people necessarily to connect to, but to find poets who are fun. I’m a very irreverent person, and I like to be transgressive. And I like to go places in my conversation and be wild. That makes life more fun and more meaningful than thinking, “Oh, I gotta connect with this person so they can help me later on.”

Blanco: I think sometimes we don’t celebrate ourselves when it’s time.

Rogow: Cornelius was talking a little bit about jealousy and envy as well. And I think it’s really important not to get to the point where you take yourself so seriously as a writer.

There are cultures in which poets fill stadiums, and the United States is not one of them, and it’s important to maintain our own sense of self—yet not get so infused with your own sense of your importance as a writer that you lose perspective. I remember somebody telling me a story of going to lunch with a poet who wasn’t all that famous, and he was also a literary translator. The service wasn’t very good in the restaurant, and the translator said, “Do you know who I am? I’m so and so, I’m the translator of blah blah blah.“

It’s still important to be nice to waiters, even if you just published a book with a major press.

Blanco: Part of what you’re saying, part of my motivation to keep on being out there, is for all of us, it’s to open doors to poetry. I work with teachers a lot. That keeps me in service to us as a community and that helps ground me. I realize you’re also like a poem itself. You’re in service to something larger every time you sit down to write. It’s perfectly fine to be jealous of the poem but not the poet.

There’s also another way of balancing, having something else to do to draw some self-worth or self-esteem. I’m a civil engineer and I was working as an engineer through all my MFA program. I wrote my first four books of poetry working as an engineer. I wrote my first book during lunch hour. When I was having a bad engineering day, I’d write poetry at work. John Lithgow, the actor, said, “Do something else while you’re waiting for the call, from the audition. It doesn’t mean following another career but painting, or being purely creative or just doing something outside of that world.

✶

O’Reilly: Social media is almost like a drug. It’s got its ups and downs. You know, there’s a place and time for it but it can also be playing with fire. If I’m looking at social media a lot I know that I’m not centered. For me, it’s a gauge.

Blanco: I’ve got to say, you made me think psychologically. One of the questions is: How much is enough? How much is enough? But I’ve realized that social media is a bottomless well. I’ve also felt like a bottomless well. And I realize where it comes from. Every time I’m getting a little too crazy, it basically comes from feeling like a defective child, a gay boy. And then I remember that and I tell myself, “Enough, you know you’re fine. That was your homophobic grandmother talking.”

Rogow: I think it’s important not to confuse fame and love. You still need your family, your community, the people who are close to you. And if you’re trying to replace that with fame, that’s a tragic story in the making.

Audience member: I just try to remember those moments before one book was published, and I would get up in the middle of the night because a poem would literally wake me up. I would start writing it out and nothing else mattered in the world.

Another audience member: A comment I’m going make about Richard is I was working on a project and I was no one. And I emailed him and asked him if he would sit down and talk to me and he did. You know, without hesitation and I found a number of writers who did the same thing. I think that level of generosity is kind of the giveback. When you’re in a position where you’ve made a name for yourself. it’s something that you taught me.

Blanco: Sometimes you work on a poem, it’s like a problem child, you work on it for hours and hours, months and months and months and months. And you’re convinced this is one of your masterpieces, it’s the problem child that finally went off to med school. And then there’s one of those poems that you spit out in a week, it gets accepted at the Atlantic and you’re like, “But no,that sucks.” But that poem was probably written without the ego so much in the way. And it just comes out. That happens all the time or sometimes, I’ll read poems that I think are my best poems and then I’ll read another one and I’m just gonna throw this one in there because it’s thematically correct for the occasion or for the moment. And people come up and say, “Oh my god, that poem.” I’m like, “What poem, that poem? That poem sucks.” Because my ego’s there. So I’ve learned to mistrust my opinion of my poems in some ways.

Audience member Michael Dylan Welch: So a comment. I remember reading Louise Glück’s book right after she won the Nobel Prize. She phoned a poet friend and said, “Are we still friends?” Because she recognized the burden that that would place on their friendship.

O’Reilly: I feel like what little bit of fame I’ve had has given me more opportunities to be kind, to be a better person, to be less reactive and to listen to people. And people come to me with questions and I just really hope I have some answers because people were that way with me. My teachers, my main mentors were Ellen Bass and Danusha Laméris and they were both extremely kind people and I just want to spread that.

Blanco: Zack, if I may, I’d like to end with a poem by Naomi Shihab Nye. Whenever I’m feeling a little weird, I just read this because I think what poetry does best is that it can be contradictory. It can examine everything upside down, inside out. “The river is famous to the fish….”

✶✶✶✶

Dion O’Reilly’s debut collection, Ghost Dogs, was runner-up for The Catamaran Prize and shortlisted for several awards, including The Eric Hoffer Award. Her second book Sadness of the Apex Predator will be published by University of Wisconsin’s Cornerstone Press in 2024. Her work appears in Missouri Review, New Ohio Review, The Sun, Rattle, Narrative, and The Slowdown. She facilitates private workshops, hosts a podcast at The Hive Poetry Collective, and is a reader for Catamaran Literary Reader. She splits her time between a ranch in the Santa Cruz Mountains and a residence in Bellingham, Washington.

✶

Zack Rogow is the author, editor, or translator of more than twenty books or plays. His memoir, Hugging My Father’s Ghost, will be released by Spuyten Duyvil Publishing in 2024. Rogow’s ninth book of poems, Irreverent Litanies, was published by Regal House. He is also writing a series of plays about authors. The most recent of these, Colette Uncensored, had its first staged reading at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., and ran in London, Catalonia, San Francisco, and Portland. His blog, Advice for Writers, features more than 250 posts. He serves as a contributing editor of Catamaran Literary Reader.

✶

Selected by President Barack Obama as the fifth Presidential Inaugural Poet in U.S. history, Richard Blanco was the youngest, the first Latinx, immigrant, and gay person to serve in that role. In 2023, Blanco was awarded the National Humanities Medal by President Biden from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Born in Madrid to Cuban exile parents and raised in Miami in a working-class family, Blanco’s personal negotiation of cultural identity and the universal themes of place and belonging characterize Blanco’s many collections of poetry, including his most recent, Homeland of My Body, which reassess traditional notions of home as strictly a geographical, tangible place that merely exist outside us, but rather, within us. He has also authored the memoirs For All of Us, One Today: an Inaugural Poet’s Journey and The Prince of Los Cocuyos: a Miami Childhood. Blanco has received numerous awards, including the Agnes Starrett Poetry Prize, the PEN American Beyond Margins Award, the Patterson Prize, and a Lambda Prize for memoir. He was Woodrow Wilson Fellow and has received numerous honorary degrees. Currently, he serves as Education Ambassador for The Academy of American Poets and is an Associate Professor at Florida International University. In April 2022, Blanco was appointed the first-ever Poet Laureate of Miami-Dade County.

✶

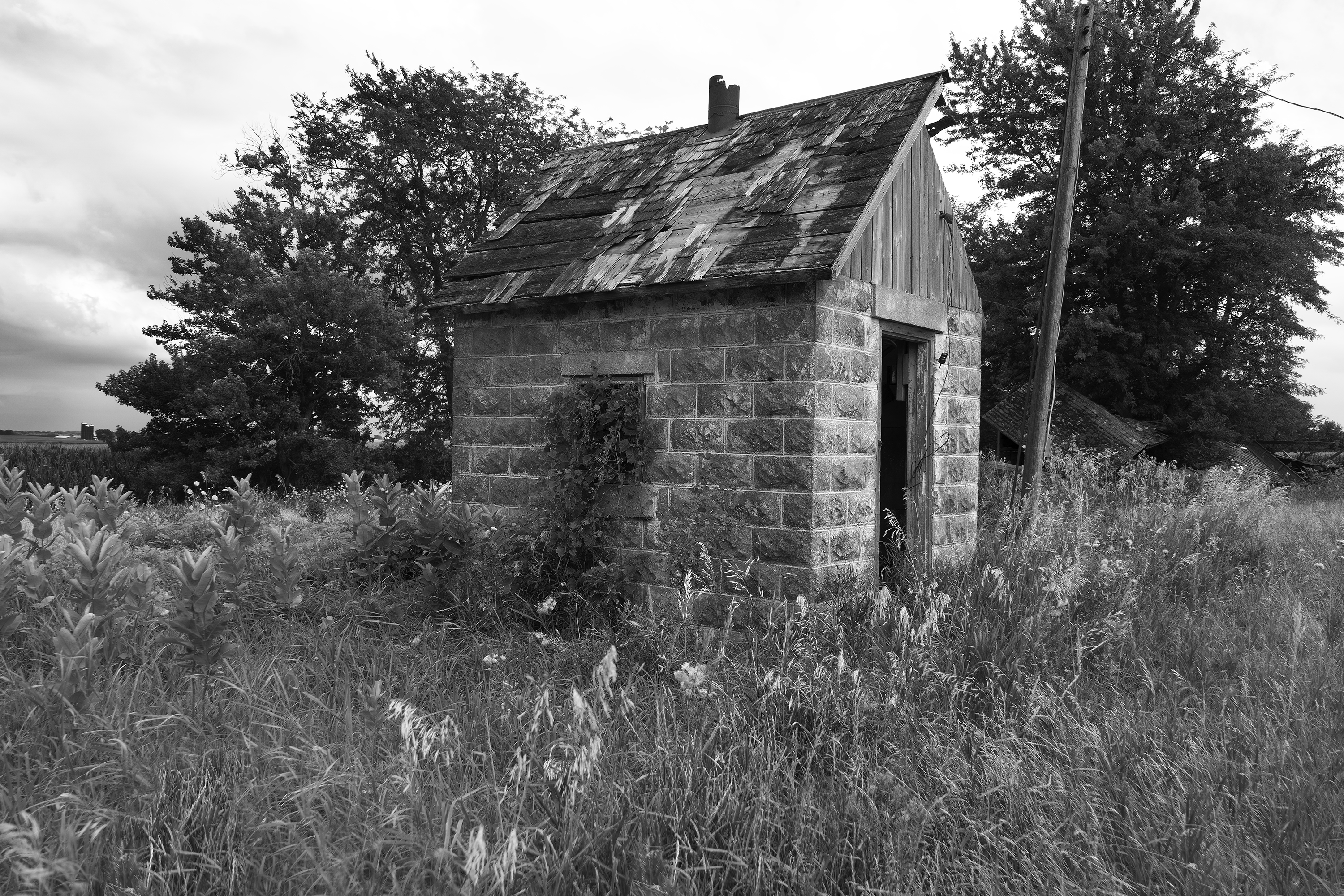

Michael Anderson takes pictures while traveling in national parks, rural counties, and cities. He carries his camera while running errands on his bicycle in Chicago.

✶

Whenever possible, we link book titles to Bookshop, an independent bookselling site. As a Bookshop affiliate, Another Chicago Magazine earns a small percentage from qualifying purchases.