Mr. Mrs. Miss. Dr.

Mia hovered the cursor over the pulldown menu as she considered the options under Title.

“That’s it?” she said aloud. She clicked and unclicked the menu as though doing so would drop down more options.

“Mrs. or Miss?” she asked her cat, whose tail curled around the edge of her laptop.

Mia rubbed her eyes with the heels of her palms. The room was dark. How long had she been scrolling through websites to plan this trip? The flights were overpriced. She took a sip from her half-drunk glass of red. That was overpriced too.

Was it even worth the bother. It would be far easier to hole up in her tiny apartment in Qatar, watch mindless streaming television, and finish grading her composition classes at a relaxed pace rather than cram it all in before break. Ten years had passed since her PhD; yet here she was, adjunct faculty, teaching four classes a semester and constantly grading essays that most of her students had no interest writing. She earned about the same money as a manager at Starbucks and worked surely twice the hours.

But on semester breaks she could easily explore the world on a budget from where she lived, so close to adventures in East Africa, Eastern Europe, the Caucasus, the Stans, South Asia, and the rest of the Arab world. She could fly direct to what would otherwise be inaccessible places, and without a red-eye. True, she often had to travel alone. Her university friends, tethered to their children, could never join her. They didn’t seem to travel anywhere. What was the point, then, of moving halfway around the world?

Mia returned to the glow of her laptop screen. Mr. Mrs. Miss. Dr. There was no Ms., definitely no Other. Maybe something was lost in translation. But these options seemed hard to translate wrong: Married or not married for women, doctor or not doctor for men. Mia had never flown this new regional airline before. Clearly they were not imagining a female doctor, even in the twenty-first century. Wherever she traveled in the region she was asked why she was traveling alone, where her husband was, how many children did she have, not do you have children but how many. It wasn’t a terrible thing to be defined by others, not if those others were her circle of friends and supportive colleagues, but when those others were supposed to be a husband and children, of which she gratefully had neither in her early 40s, it felt suffocating.

Her cat stepped across her keyboard, paws pressing keys, and with a “tsk” Mia lifted her off the table to set her on the floor. On the screen, Mia found that her cat had selected Dr.

Dr. She was a doctor. Okay, a PhD in literature. She never selected the Dr. option on any forms. But why not? Was she at some level ashamed of adopting this title and pretending that it carried the same prestige as a medical degree?

Dr. She imagined herself on the plane: some passenger has a medical emergency, a flight attendant approaches her row for help only to have her have to explain that her title, in fact, reflects a PhD, in literature, and that she is not a doctor in the sense that they were hoping. What a nightmare.

But still, Mrs.? Or Miss? She was definitely neither of those. But at least she was a doctor.

It was late. She yawned, could not finish her wine and poured it back into the bottle, dripping it down the side and staining the label. There was no point delaying the purchase of these tickets any longer. She left her title as doctor.

✶

The gate at the airport was crowded, and the airline staff announced that the flight was full. Her ticket indicated a middle seat, in boarding group nine. Nine?

Be grateful, she thought, that you can even do this at all. A couple tried to calm a screaming child, their eyes darting around the room in helpless embarrassment. Already, a screaming child. She set her latte on her carry-on roller bag and pulled out Sister Carrie from her tote bag. The paper cover of the 500-page novel had torn. Why did she feel compelled to read it? A literary classic? Duty to her field?

The staff announced the flight was to begin boarding, and passengers crowded the gate. She did not join the horde, especially given the slim chance of finding overhead room for her carry-on in boarding group nine. Why fight it. She opened her book. She read. She learned that Sister Carrie was pretty with the insipid prettiness of the formative period. Five hundred pages of this. She took a deep breath.

The staff announced final call. She rolled her bag to the agents scanning the tickets. They made her check her carry-on, of course, and the queue of passengers on the jet bridge seemed interminable. At the plane door, the flight attendant pointed her down the aisle to her seat as though there were any other way to go. People ahead blocked the aisle as they seemed to purposefully prolong sliding their luggage in the overhead compartments. She counted sixteen seats in the first-class area, completely full. All men. No: there in the corner of first class, one woman, dressed like a Western expat, wearing a ring and, predictably, talking to a man next to her. All the flight attendants were women. She imagined herself back in 1950 doing the same exercise, counting all the men, counting all the women serving men.

In her row, a husky man in the aisle seat angled his thick legs to suggest that she climb past him to get to the middle seat. She asked if he wouldn’t mind stepping into the aisle to let her through. He stood with a look like someone had splashed water on his face, and grunted a few words. British, she detected from his accent, and not of the polite sort, more the colonial type who felt he should have been in first class by virtue of nothing. At the window, another man had slumped asleep and was already sprawling into her space. She slipped in and sat, pressed her legs together and tucked her elbows into her sides so as to not touch either of these men. She felt small.

There were no video screens. As the plane taxied along the tarmac, the cabin crew performed the safety demonstration like some ancient ritual, synchronized, routine, and pointless. Mia watched with fake interest and made a mental note of the emergency exits, as requested. Minutes later the plane rolled down the runway, accelerated, and jostled its way into the sky and over the Gulf. The plane soon flew among cumulonimbuses that soared higher than Mia could see through the window of the row in front of her. The man next to her had shut the shade and was snoring. What a waste of a window seat. The husky man on the aisle had his elbows on both armrests.

The setting sun cast pinks and reds upon the clouds. Mia mentally practiced the sequence after landing: Disembark, shuffle through customs, present her visa, get cash, rehearse the words for “no thank you,” brace herself for the gauntlet of harassing taxi drivers outside the airport. Soon she would face the unknowns and trials of yet another developing country as a solo woman traveler. Why did she do this to herself? Was she no longer excited about this trip? But this was the same mental script on every flight to a new country, with the same panic. Every time, things worked out fine. She never regretted a trip on the flight back.

Mia heard a shout from the rear of the plane, and several passengers turned their heads. Mia did too, as did her seatmate on the aisle, but she saw nothing. A flight attendant jogged past toward the back. Some of the other passengers’ faces looked frightened. Her seatmate barked a nervous laugh and said, “Not my problem.” Mia wondered what exactly the problem was but turned to face forward in her seat. It was none of her business. At least she and her seatmate could agree on that.

She opened her book. The flight attendant returned to the front of the plane, shoes pounding the aisle, then reappeared several rows ahead of Mia reading a sheet of paper with great concentration. She bent down to speak to someone.

Mia’s eyes scanned the page of Sister Carrie but didn’t register anything. Ahead, the flight attendant had returned to the sheet of paper in her hands. She approached to two rows ahead of Mia and squatted to speak to another passenger. Mia could not hear much of the conversation, except for a man who spoke loudly to say “yes” and “cardiologist.” Mia heard more mumbling. The flight attendant stood with her mouth pressed into a worried smile. She consulted the paper again, then approached two more rows to Mia’s.

“Stewardess,” the man sitting on the aisle seat said with his finger pointed in the air. “Can I get a Coke?”

The flight attendant checked the row number printed on the overhead compartments, consulted her paper, then looked directly at Mia. “You are a doctor?”

“No,” said the man on the aisle seat. The flight attendant locked her eyes on Mia, who looked at her seatmate on the aisle, then at the man slumped in the window seat, before returning to the flight attendant and pointing to herself in confusion.

“You are…” the flight attendant said glancing at her sheet of paper, “Dr. Mia…” She had a thick accent and struggled with Mia’s last name.

Mia didn’t know what to say. Was this not her nightmare?

“Your ticket says you are a doctor.”

“Yes,” Mia said. “I did put that down. I’m sorry. I’m not a medical doctor. Is everything okay?”

“What kind of doctor?”

The question threw her off. It felt personal. “Literature,” she answered defensively. But then, she wasn’t going to teach anybody anything about the types of doctors in the world. She softened. “I’m a doctor of literature.” The flight attendant’s eyes brightened.

“PhD,” Mia continued as though to clarify. “Doctor of philosophy.”

“I need to speak to you,” the flight attendant said, gesturing toward the aisle. Mia stood and squeezed past the knees of her seatmate.

The flight attendant spoke to Mia in confidence. “We have a situation. There’s a passenger who is sick. Will you help us?”

Mia wasn’t sure the woman understood. It was clear that English was not her first language. “You must be mistaken,” Mia said. She pointed toward the cardiologist. “There’s a medical doctor right there.”

“It’s urgent,” the flight attendant said. “Please.”

She led Mia down the aisle. The other passengers turned toward her with faces of concern and interest as though Mia had the talent or the skills to handle the situation. Mia shook her head to answer them all No. In the rear section of the plane, another flight attendant was hovering over a young man in the aisle seat of an otherwise empty row, as though the flight attendants had moved him there or the passengers seated next to him had left out of discomfort. The young man was breathing heavily, his elbows on his unfolded tray table and a hand over his face. Tears streamed down his cheeks.

“Did you mean maybe a psychiatrist?” Mia whispered to the flight attendant. “Or a therapist?”

“Look!” the flight attendant said with impatience. “The heavy breathing. The hands on the face. The groans. And of course the paper.”

The young man was slouched over a torn-out notebook page. Mia saw words, some scratched out, and a broken plastic pen. A tear dropped onto the paper and blended into a pool of leaked ink.

He muttered something, and the flight attendant beckoned Mia closer.

“I can’t do this,” he sobbed. His breathing accelerated to hyperventilating. The flight attendant reached under his tray table to retrieve an airsickness bag, which she shook open. She instructed him to breathe into it. It calmed him a bit.

Mia now understood. The tear-stained paper, the broken pen, the scratched-out words.

Mia leaned over the man from her position in the aisle and put a hand on his shoulder. “Excuse me,” she said. “Can I see what you have?”

The young man choked on another sob. “It’s…,” he said, followed by more tears, then, “I can’t do this!”

“Just show it to me,” Mia said as she tugged gently at the paper that was trapped under his elbows. The young man lifted his arms enough to let Mia slip it out from underneath.

The first word on the page was “Roses.”

Mia winced. She read further. It was unmistakable. A love poem. He was writing a love poem. But the threadbare metaphors. The adverbs. And the rhymes. She kept a neutral face.

A flight attendant tapped Mia’s shoulder and whispered. “We’re not even close to another airport. The pilot said an emergency landing could be dangerous.”

Mia nodded. “I’ll need a pen, a fresh sheet of paper, or a notebook if you have it, a cup of coffee, some soft tissues, and a blanket and pillow.” One of the flight attendants nodded and hurried toward the galley.

“Can you stabilize him?” the other flight attendant asked.

Mia nodded, but without complete confidence.

“Can you?” the flight attendant repeated.

Mia nodded again. “Yes,” she said. “I can do this.” She turned to the young man. “Would you mind scooting over?”

The man slid to the middle seat, and Mia took the aisle as the first flight attendant returned with the requested items.

What would a doctor say? Mia smiled. “You’re going to be fine,” she said to the young man as the flight attendant handed her a pen. “Just fine.”

✶✶✶✶

PJ Henry is a psychology professor at New York University Abu Dhabi with a love for reading and writing fiction. He grew up two hours north of Chicago just outside Milwaukee, and later lived in Chicago for several years as a professor at DePaul University. He resides in Abu Dhabi and New York, but Chicago will always be the Big City. He thanks Piia Mustamaki for inspiring this story.

✶

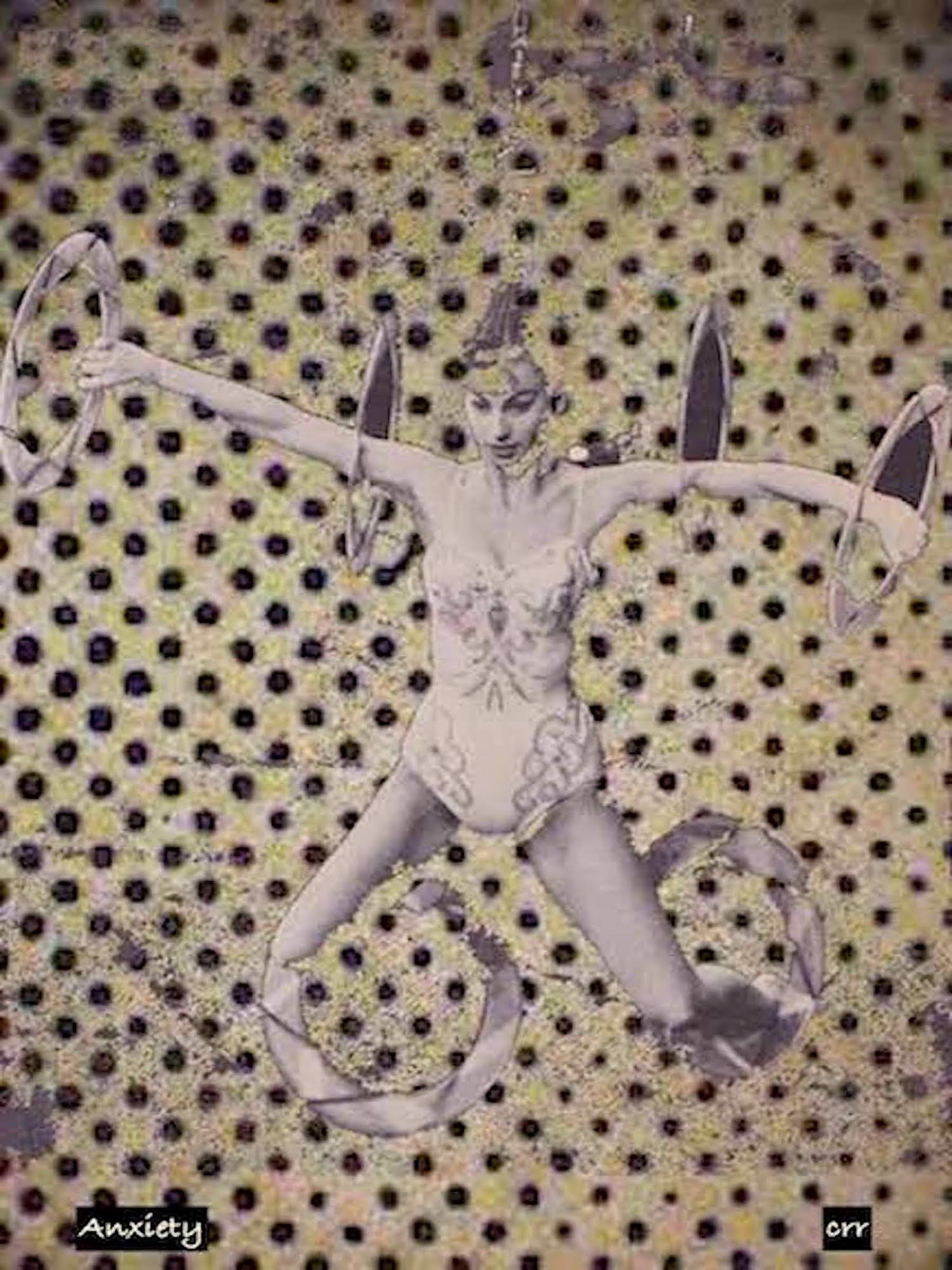

C. R. Resetarits is a writer and collagist. Her collage art has appeared on the covers and in the pages of dozens of magazines and book covers.