Tolsun Books, August 15, 2023, 206 pp.

Introduction

“It doesn’t matter who my father was; it matters who I remember he was.”

—Anne Sexton

In Bloom

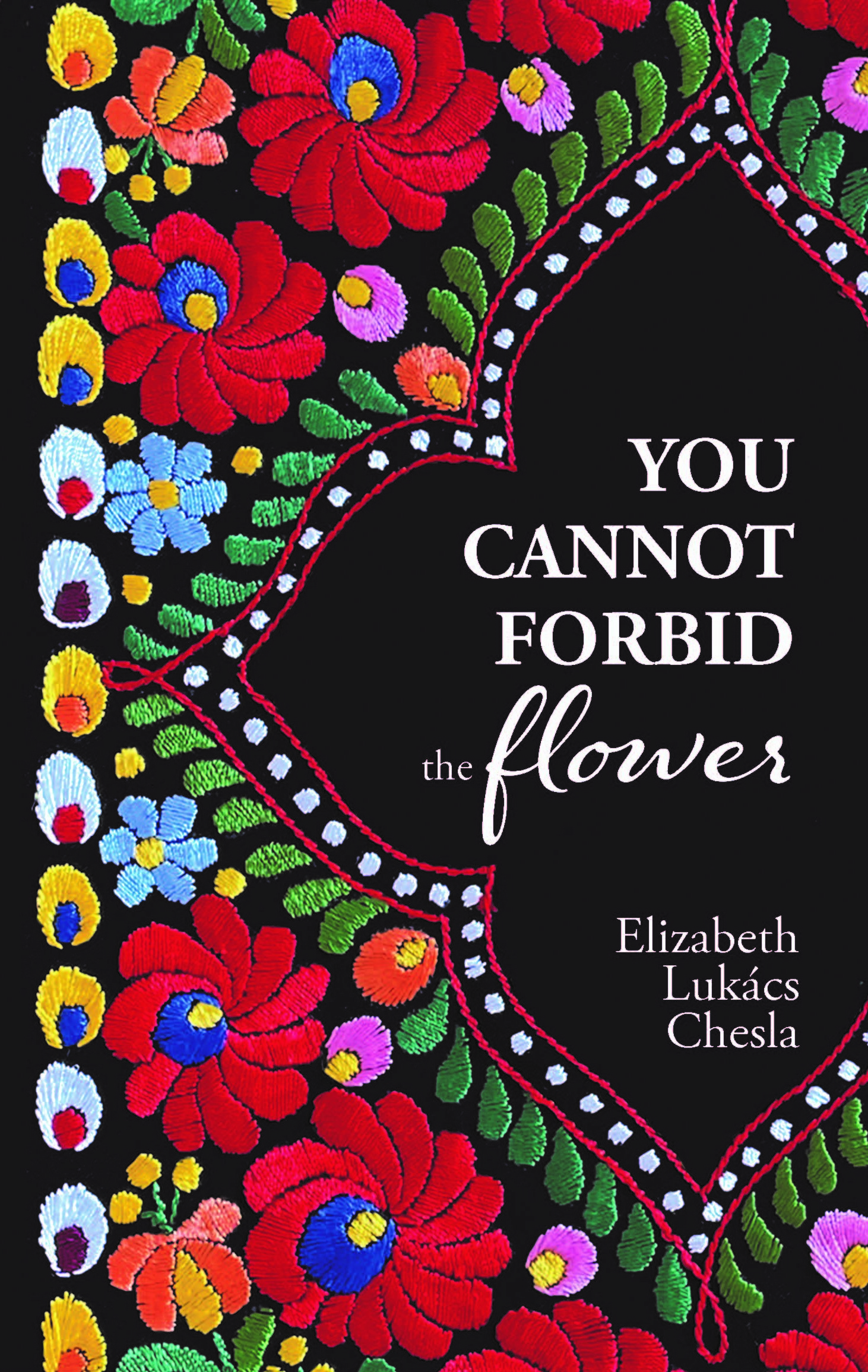

In our house, the flowers are everywhere: on tablecloths and doilies, on napkins and dishtowels, on aprons (of course on aprons), on book covers and bookmarks, on bedcovers and pillowcases, on scarves and blouses and boxes. Some are edged with lace; some are embroidered on lace. There are many different flowers—tulips and violets, lilacs and edelweiss—but mostly the peony, the Matyó rose. There are many colors, but mostly rich red on raven black. In traditional Matyó folk art, red is the color of joy.

Even when my parents divorce and our house divides, the flowers remain. Even when my mother forbids us to speak Hungarian, when she stops cooking Hungarian foods, when we no longer wrap szaloncukor candies to hang on the Christmas tree. Even when my father is too far away or too drunk or too broken. Stitched by hand onto linen, cotton, and lace, the flowers are always in bloom.

My Father Is Dying

January 2005

I have driven three hours, stopping halfway at a rest stop near Scranton to pee. I am only a few months pregnant, but this is baby number three and already my bladder won’t hold. When I arrive, I will take my father to chemo or radiation, stop at the grocery store and pharmacy on the way home, and make him a dinner he will try but mostly fail to eat. Instead, he will smoke, have a shot of brandy. “It’s a little too late to stop now, don’t you think?” he will say. After the first few times, I no longer argue.

My husband will call me when the kids are ready for bed so I can say goodnight. I’ll call him later, when the kids are asleep and my father is passed out in his armchair, and cry. I’ll sleep a few hours, make my father a breakfast he’ll try but mostly fail to eat, run a few more errands, and drive back home. A few days later, my husband will make the same trip. Back and forth we go.

After a while, things start to look better. The tumor in my father’s lung shrinks; my belly grows. We both put on weight, and he starts flirting with the nurses again. Then the cancer metastasizes to my father’s brain, invades it like an army, garrisoning troops in his cerebellum. He starts losing his balance, losing weight, blacks out driving home. The tumor is inoperable, the cancer spreads. It is only a matter of time.

Three Memories I Have of My Father With a Gun, in Reverse Chronological Order

3. Standing with my father on the ridge, the highest point of his property, the day he teaches me how to shoot. I am twelve and terrified: of the gun, of falling off the edge, of disappointing him.

From this side of the ridge, we can see all five ponds on his property; from the other side, Canada. The lily pads are dime-sized dots in the distance, perfect targets. My father stands behind me to help me adjust the rifle, tells me to aim through the crosshairs. He steadies me, then steps away. I shoot, scream, and stumble a few steps backwards, surprised by the strength of the recoil. My father laughs, tells me I missed by a mile. He lets me try again. He is not disappointed.

2. Watching my father shoot a porcupine he has tracked and cornered in a tree. “They’re killing the trees,” he tells me, showing me a wide stripe where the bark has been chewed almost all the way around the trunk of a sugar maple. One shot, and the porcupine falls, blood trickling from the wound in its side. I am ten and horrified. My father has nearly 200 acres. Do a few dead trees really matter? I know better than to ask, but I can’t swallow the question. It buries with the others in my throat.

1. My father chasing my mother out of the house. She threatened to leave after he punched another hole in the wall; he threatened to get his gun. She holds my little sister, hurries my brother and me out the front door. I am six and terrified. Does he point the gun at her, at us? I only remember the running, in our pajamas, into the car, into the night.

A Hungarian Fairy Tale

Once upon a time, long ago in northern Hungary, the land of the Matyó, a beautiful boy and girl were deeply in love. It was winter, and in that bitter cold, their love kept them warm. In spring, they would marry. But one day as the boy walked the girl home, a light snow falling on their shoulders, the Devil, who’d been admiring the boy’s beauty for some time, kidnapped him, whisking him away just as he was about to give his love a kiss.

The girl was devastated, but a hard peasant life had taught her to do what must be done. It wasn’t the first time she’d faced a demon, and it wouldn’t be the last. She went straight to the Devil’s lair and demanded that he release her lover.

The Devil laughed, but he was impressed by her audacity. “Alright,” he said, deciding to have a little fun. “I’ll make you a deal. Fill your apron with the most beautiful flowers of summer and bring them to me. Then you can have your lover back. You have three days.”

The girl wept all the way home, for the Devil had given her an impossible task: the land was frozen solid, the fields were covered in snow, and it would be months before the first flowers began to bloom.

But the girl was determined, and when she got home, she built a fire and picked up her embroidery. The rhythm of the stitches, she knew, would calm her down, help her figure out what to do. She looked at her work: a circle of violets and lilies surrounding a magnificent red peony, a perfect Matyó rose hiding the tear she’d repaired in the fabric.

Suddenly the girl realized that she could do as the Devil asked after all. She took off her apron and began at once to adorn it with peonies: bright red and brilliant white on raven black, tiny buds and glorious blooms, green stems and leaves intertwined like the limbs of lovers. She added tulips, filled in small spaces with violets and edelweiss and lilacs. For three days and nights she sewed, not even stopping to rest. When she finished, she brought her apron to the Devil. Even he could not suppress a gasp. It was more beautiful than the true flowers of summer.

The girl had done what he asked, and the Devil released the boy.

Since then, they say, the boys and girls of Matyó wear clothing embroidered with bright, colorful flowers to protect themselves from the Devil.

Six Facts about Peonies

- Peonies are considered perfect flowers, having both types of reproductive organs.

- They come in all colors except blue.

- They have traditionally been used to make medicines to relieve headaches, asthma, and the pain of childbirth.

- Their buds secrete a sweet, sugary sap that attracts ants. It is a strategic move: the ants feeding on the sap protect the flowers from harmful insects.

- Their roots run very deep.

- They were my father’s favorite flower.

After my father died, after a quiet funeral service to which only my sister and I, our husbands and children, and my father’s next-door neighbors came, before I allowed myself to grieve, I planted peonies along the side of the house, out by the pool, up by the shed. Bright red and white with deep green stems and leaves, my father’s perfect flowers wave the colors of the Hungarian flag, dig their roots deep.

Part I

in which my father finds himself at war and in love

My Father, Young and in Love, Shoots a Russian Soldier

October 1944

It was World War II, and my father was seventeen and in love with a girl he’d never even spoken to. It was love, though; he knew it by the crush in his lungs and the sweet sting on the back of his hands each time his teacher beat him with a bamboo stick for daydreaming. He knew it by the way every subject came back to her: how he wanted to know her history, explore her geography, study the chemistry of love. The world had come alive in a way he’d never known it could. Everything felt on the edge of exploding.

My father’s family lived on the outskirts of Gyergyószentmiklós, a small Transylvanian city in the heart of Székely Land, nestled in the folds of the Eastern Carpathian Mountains. Before the Nazis occupied northern Transylvania, before the Russians crossed the Carpathians to liberate Hungarians from fascist rule, when the land still belonged to Hungary, as it did for nearly 1,000 years, my great-grandfather, Count Lukács of Gyergyószentmiklós, owned hundreds of acres of farmland between the city and Red Lake, also known as Gyilkos-tó: Killer Lake.

But in 1920, as punishment for Hungary’s role in World War I, all of Transylvania, land of nearly two million Magyars, was given to Romania in the Treaty of Trianon. Under Romanian rule, my great-grandfather lost his title, lost most of his land, and found himself in a persecuted minority, even though Hungarians made up nearly ninety percent of the population in Székely Land.

Life was difficult for my family. Then, in 1936, when my father was nine, the prime minister of Romania contracted my grandfather, a master builder, to build a grand hotel. With over one hundred rooms, the Casa Alba would be a marvel, a luxury stay on the shores of Red Lake, facing the great cliffs of Kis-Cóhard mountain.

My grandfather knew he might never get an opportunity like this again. For the next four years, he put everything into the project while my father and his siblings—by now there were five—lived largely on bread and potatoes, wore shabby shoes, mended and remended their clothes. The Romanian government only ever paid my grandfather enough to keep the work going. He’d get the rest, they promised, when the hotel was finished.

But when the hotel was complete, when my grandfather had done all that he was contracted to do and more—“The inspector,” my father tells me, “said everything was perfect”—the prime minister refused to pay my grandfather what he was owed. This was not, as my grandfather believed, simply because he was Hungarian. The prime minister knew that northern Transylvania was about to be handed back to Hungary—and in August of 1940, in accordance with the Second Vienna Award, it was. The Hungarian government, upon learning how much my grandfather was owed, bought the hotel at a fair price and turned it into a retreat for the country’s top athletes. Thanks to Germany and Italy, after years of scarcity, my father’s family finally had plenty.

Four years later, near the end of the war, the northern half of Transylvania, including Gyergyószentmiklós, was once again given to Romania by the Allied powers. The mountains were still the same, and the cliffs of Kis-Cohárd, and Red Lake with its petrified tree stumps like tombstones. People who had not escaped or been killed still lived in the same houses, with the same neighbors, on the same streets. Nothing changed, yet everything changed. Gyergyószentmiklós became Gheorgheni became Gyergyószentmiklós became Gheorgheni again. Yesterday, all Hungarian children had to learn Romanian; today, all Romanian children must learn Hungarian; tomorrow, Romanian again. Minority, majority, insider, outsider, one of us, one of them. Invisible hands stitched the borders, pulled the thread.

On the day my father shot a Russian soldier, a crisp October morning in 1944, Russia’s Red Army had reached the outskirts of Gyergyószentmiklós. Advancing steadily from the south and east, Soviet and Romanian soldiers battled German and Hungarian troops, with most of Transylvania caught in the crossfire. As the fighting neared, my father and his classmates were each given a rifle and an army hat, divided into groups of ten, and led toward the front by a German soldier.

They were not many, and they were scared. None of the boys had ever been in combat, and the basic scout training they’d had in school would be of little use against the Soviets and their Kalashnikovs. The Germans kept their instructions simple: Keep your mouths closed and your eyes open. If you see a Russian soldier, shoot.

My father did not want to take a Soviet life on behalf of the Germans. He did not want to fight at all; he was seventeen and in love and afraid to die.

My father’s unit hid in an abandoned farmhouse in the woods a few miles from town, just south of Killer Lake. For three days they waited, with almost no food and just as little sleep, staying as still and silent as possible. On the third day, just after dawn, my father, scanning the woods for the thousandth time, heard the snap of a branch. Then another.

Maybe it was fear, or the lack of food and sleep, or the way the morning light was just beginning to slant between the trees, but for a moment my father thought he saw Csodaszarvas, the mythical miraculous stag who led Hunor and Magor, sons of Nimrod, westward across mountains and meadows, through valleys and swamps, to the women they would take as wives and the rich and bountiful lands upon which their descendants would found the glorious nation of Hungary.

My father took a deep breath, adjusted the rifle against his shoulder, and waited. There was a quiet rustle, then the red star and red lapels of a Soviet uniform. He remembered what his father said when he left for the front two years earlier: You fight for your homeland.

My father put the red star of the soldier’s cap in his crosshairs, pulled the trigger, and crouched down to reload. When he stood up to shoot again, the soldier was gone.

Many years later, my father tells me, “I don’t know if I killed him. I just know he wasn’t there anymore.”

That evening, orders came in to retreat immediately and evacuate. The Germans had a plan: let the Russians occupy Gyergyószentmiklós, then bombard the city. Those who chose to stay, if they survived the Russians, would not survive the bombs.

The Legend of Killer Lake

Once upon a time, not so very long ago, Eszter Fazekas, a great beauty even among the beautiful people of Székely Land, fell in love.

Eszter, slender as a fir, with lips as red as a Matyó rose and hair as black as the apron it was embroidered on, was at the Szentmiklós market choosing plums to make szilvás gomboc, her favorite dumplings, when she felt someone’s gaze upon her. She looked up with her gray-green eyes at the most handsome boy she’d ever seen. Love struck them both like lightning.

The boy bought Eszter a heart-shaped cake and a sky-blue scarf and asked her to be his wife. Eszter agreed, and the two eagerly planned their wedding. But before they could marry, the boy was conscripted into the army.

Eszter was heartbroken. She waited for her love, and waited, and waited, but day after day after day passed without his return. Eszter fed the Vereskő Creek with her tears and took what refuge she could find in the beauty of the valley—the creek, the giant cliffs of Kis-Cohárd, the mountainsides blanketed with firs.

One day as Eszter walked along the creek, singing a mournful song, she felt someone’s eyes upon her. From the cliffs above, a thief was watching her. As if struck by lightning, he fell in love.

The thief galloped down the mountain and immediately proposed to Eszter. Of course, she refused. Nothing the thief offered—gold, silver, a palace made of diamonds (he was a very rich thief)—could turn her heart from the one she loved.

Well, the thief was used to taking what wasn’t his. Determined to make Eszter his wife, he swept her onto his saddle and kidnapped her, just as Hunor and Magor had kidnapped their wives centuries before. He kept Eszter prisoner in the Hagymás Mountains, hidden in the caves of Kis-Cohárd. Day and night, the thief repeated his offers of gold, silver, a palace made of diamonds, determined to make Eszter love him back. Day and night, Eszter pleaded with the thief to set her free.

The thief soon lost his patience. “Enough!” he told Eszter. “Tonight, I make you my wife.”

Eszter was devastated, but she knew a trick or two. “So you will not be taken,” her great-grandmothers and their great-grandmothers had said, and hid self-defense moves in their folk dances. Eszter feigned resignation, and as night fell, she said to the thief, “First, we dance.” The women in her family had taught her well, and when the moment was right, when the thief took her hand to spin her around, before he pulled her close, Eszter spun the thief’s arm behind his back, struck him like lightning in the throat, and fled into the mountains.

Eszter knew the thief would not be far behind and cried out to the mountains for help. The mountains began to cry and tremble, and a torrent of tears rained from the sky. Soon the earth softened and crumbled, tumbling down the mountainside, burying the thief and Eszter and everyone in the tiny shepherd village below.

The landslide blocked the path of the Vereskő, whose waters soon swallowed the pine forest. The valley became a lake, turned red by the blood of the people buried beneath the stones: shepherds and their sheep, a thief, and Eszter, whose gray-green eyes you may feel upon you as you look into the water. The tops of the petrified trees rise from the lake like tombstones.

A Brief History of the Treaty of Trianon

In which we learn that after Hungary’s defeat in World War I, on June 4, 1920, the Big Four powers of Britain, France, Italy, and the United States presented to the Kingdom of Hungary in non-negotiable terms the Treaty of Trianon, which cut Hungary to two-thirds its size, giving territory in the north to Czechoslovakia, in the west to Austria, in the south to Yugoslavia, and in east to Romania, making Hungary a landlocked nation and shrinking its population from nearly twenty-one million to just under eight million;

after which some thirteen million Hungarians suddenly found themselves minorities in foreign countries, including more than five million Hungarians in Transylvania;

in which we use the following words to describe what happened to Hungary as a result of that treaty: dissolved, disintegrated, dismembered, tragedy, catastrophe.

✶

Copyright © 2023 by Elizabeth Lukács Chesla. Published 2023 by Tolsun Books. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

✶✶✶✶

Elizabeth Lukács Chesla is the daughter of Hungarian refugees and a mother of three. She writes, edits, and teaches from the suburbs of Philadelphia. You Cannot Forbid the Flower is her first book of fiction.

✶

Whenever possible, we link book titles to Bookshop, an independent bookselling site. As a Bookshop affiliate, Another Chicago Magazine earns a small percentage from qualifying purchases.