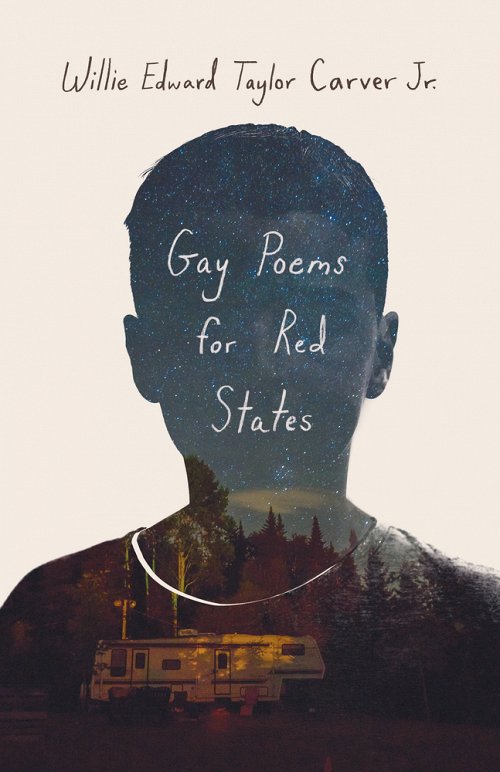

University Press of Kentucky, 2023, 120 pp.

Minnie Mouse Toy

“Would you like a Hot Wheel or a Barbie, sir?”

The words float like ghosts in front of me

when I speak them, frozen by the winter air

whipping in through the drive-thru window.

“Boys’ toy!” Gruff. No a. Just boys’ and toy. Two words.

“Okay. We have Hot Wheels and Barbies.”

“No wonder you work at McDonald’s, you idiot.”

Idiot.

I am five again.

My mother’s knee-length, interstate-cold

denim coat is a traveling house.

When I stand close enough, I smell

floor cleaner, cigarette smoke, minty gum.

Home.

The bright lights of McDonald’s

are a circus of plastic, shining glee;

my tiny heart twists with such rapture

that I feel dizzy and hug the clouds

of home that are her coat.

My mom clears her throat.

“Could I get a Happy Meal with the Minnie Mouse car?”

The words are soft like the quilted lining of her coat,

and each petal of a word builds a flower of please.

The cashier hammers a few buttons

and yips our order into a thin microphone,

but then her eyes grab me

and drag me from the coat.

They look me up and down and tug at my shirt.

I pull the coat closer until I am surrounded

by the smoke and gum and cleaner

and can feel the blankets on my bed

piled around me.

But I hear her through the imaginary walls

as she hands the boxed meal to my mother:

“You know you’re gonna ruin him?”

The words lodge themselves

into the foundation

of the imaginary home.

It dissolves,

and suddenly

I am just a boy

near a coat

in a bright place with nowhere to hide.

“Thank you.”

The flowers are dead. They fall fast to the ground.

My mother carries the cartoon-colored box to the booth,

drops a pack of menthols on the gleaming tabletop,

and gently directs the toy car to the side of the cigarette box

as she lights up a cigarette,

exhales a whispering cobalt storm cloud of mint and worry,

and then fights gravity to pull the edges of her lips into a smile.

“Go ahead and play, bubby. We can eat after mommy smokes.”

She tries to ash her cigarette.

I try to play.

The toy car is as heavy as her smile,

and like the smoke,

I know the weight of it is my fault,

and unlike the smoke,

I can’t make her feel better.

The plastic is too thick

and the paint on Minnie’s pink hairbow

looks like my little baby cousin’s cheeks

that change from white to red

while she screams, crying,

and her mom begs her to stop.

I look to my mother’s face.

I pull myself up from the memory.

I am sixteen. I am in a drive-thru,

and the word idiot is snowing on me.

Hard to Take Seriously

I thought Mr. Weilder was gay.

He wasn’t, but you can understand my confusion since he got emotional

when we read a poem by Sylvia Plath about her controlling father,

always waited moments before responding to our questions

with woolen words soft and sweet around the edges,

and once apologized for using pink and blue highlighters for boys and girls,

suggesting the colors were cliché and sexist.

He was a dry and foreign sprite in the threadbare and muddy hills of Appalachia.

Of course I loved him

and with all my might wanted him to see me,

to weep over my words,

to worry about the politics of my color choices,

to hear my question and look me in the eyes and wait years before answering.

In ninth grade, I joined his speech and drama team.

We met in the double-wide trailer behind the school.

An overworked aunt of a building, it served dozens of functions

when the regular school building was too busy,

and despite being neatly put away against the hillside,

it was always warm and unmoved by the depressed November fog,

standing quiet by the hill like it was having a work-break cigarette in the cold.

We all read the same poem out loud the first day, and after I read,

Mr. Weilder told me I had a strong emotional range

(even though every cell, organ, and system in my body

was feeling only the light bursting out in churchsong

as the bonds of all of my atoms burst apart

by the pull of the single emotion of pride).

We settled on an excerpt from a psychological thriller by Robert Bloch

that I was to memorize and recite in its entirety.

I recited it.

I licked every word in the story, to know its taste,

so that I could let people know which words were bitter, which made honey,

and which held fire quietly burning between consonants.

I wedged the sentences into my uncles’ mouths

to see what secrets the punctuation held;

I insisted the dialogue drive off my grandmother’s tongue

and took notes on its speed and gear;

I poured the vapored phrases into Mr. Weilder’s lungs

and took pictures of each verb as it escaped his airways

to see which ones reflected light.

For months, every Saturday morning,

I performed for my sleepy-eyed mountain classmates and caffeinated coach

in the time-faded Polaroid of that wood-paneled trailer

as seriously as if the moth-eaten curtains were Phoenician purple drapes

adorning a fully populated, columned Colosseum

and the desks rose from the floor like marbled stands.

I made first place in our local competition.

After quietly helping form the whispering, shadowed background blur

of exactly one thousand baseball and football games

fought and conquered by my brother and sister,

I, for once, got to share a cake with my family

provided by and baked with my power to use words.

The spring Kentucky state competition was at a university

on the other end of the state,

and the judges would be professors

with capital letters and punctuation following their names

and who lived in pitch-roofed houses

with sidewalks and mailboxes

like on television.

I learned what Columbia blue meant

because we had to wear matching button-up shirts.

The university was large and clean and smelled rich and artificial.

Sienna-bricked architecture tread proudly across campus

with diplomas proclaiming script-printed names

like Augenstein, Zacharias, and Pierce Hall,

which weighed a lot

to a boy who knew grown men

named June-Bug and Chigger.

I fought.

I pulled myself out of the photograph blur until others could see me,

straightened my Columbia blue button-up shirt that my mom had ironed for me,

and strode nervously to the front of the room

to recite the story.

The words flung themselves out of me in a syncopated waterfall,

each drop knowing when to slow or stop,

each stream knowing when to join or crash,

each rapid knowing when to bubble or smooth,

summiting at a bustling stream of words that breathed and saw and felt.

I was speaking into existence an old friend

as if I had been given an incantation

who could comfort and inspire at the same time.

I had never performed so well.

Mr. Weilder received our scorecards and comments.

He said some words before handing them to us,

but I didn’t hear them because I excitedly reached for the card

twenty times in my mind

before he handed it over.

The handwritten words sucked the color from the room

and punched me in the same chest

that had only minutes before been capable of

reciting magic spells with its breath:

“Hard to take seriously with your accent.”

Years later I would drink enough alcohol

to feel the room spinning out of control

(in part to forget moments like that this one)—

this same harbinger spin flung me about the university cafeteria

as if my body were feeling the resultant drag

from the force of thousands of beams of starlight

all leaving my body at once.

Hard to take seriously Hard to take seriously Hard to take seriously

Hard to take seriously Hard to take seriously Hard to take seriously

The extinguishing would have been complete

if not for the slow coal-ember fire of Mr. Weilder,

who told me that I couldn’t listen to the comments

because there was nothing wrong,

and everything right, with the way I spoke.

His words trickled down the side of my face,

thick with coal sludge.

There were two rounds to go.

My ears and mind were cut by the crisp consonants

and iron-clipped vowels of the recitations given by the other students,

who no doubt hailed from cities that were large enough to be shown on maps.

I quietly swept myself out of the classroom

before anyone could hear me talk.

Sometimes a person will speak truth

that comes to them years before they are able to live it,

a prophecy and testament to the promise and power of words.

In the third and final round, a woman wearing a blazer called my name.

I stood at the podium and felt my ancestors reinforce the steel of my bones.

“Before I speak, I already don’t care what score I get because the first judge mocked how I

talked. I don’t think she was qualified to judge me.”

I promise to that boy standing

to live up to the spell he cast that day.

Under the Pews

Little boys in country churches

can play with Matchbox cars under the pews

because the grown-ups assume

that they’re really too little to understand the preaching.

I held onto that Matchbox rule too long,

with my grasping imaginary arms that were pulled until they broke,

and until the adults said that I was too old to play cars under the pews.

I was always big enough to understand the preaching.

Hellfire would scream throughout the little wooden church,

opening fire from the pulpit.

I worried the words were aimed at me,

so I would drag myself under the seated churchgoers and think that if only

I could imagine hard enough that the little cars were real

and that inside of them were little people going to nice little homes

and having nice little suppers with nice little friends,

then I could be somewhere else with them

and not get shot.

But my imagination proved weaker than their artillery,

and the broken sieve of my ears couldn’t sift out

reminders that my little gay body would soon burn in hell

and be gnashed upon by teeth as I begged for water;

once I put my fingers in my ears and rapidly and noisily ground my teeth

in anxious, scuttling bites

as if my teeth were trying to run away against each other

so that I could get between my mind and the spraying bullets,

but I still heard the whole sentence as it

shot holes in the back of the bench:

“They make caskets for children, and you could die and burn in hell tonight.”

I ground my teeth so violently

and pushed my open palms against my ears with so much fear

that my aunt noticed my reddening face and shook me back into their reality

to ask me what I was doing. I panicked, because

being afraid of a sermon was proof I was bad,

and so I quietly whispered, “I’m praying.”

She fell without hesitation to her tired knees,

landing on cheap carpet glued to a particleboard floor,

facing the bullet holes, and bringing her head against

the wood that was worn thin by years of women polishing it

and the constant wear from the weight of worries and burdens

that fractured men brought into the church

hoping to leave them with God.

Twisted around on herself and facing the pew,

she brought her hands together,

and she began to fervently pray with her nephew.

The only thing I could do

was talk to God with her,

and so I began to pray

with all my might

for the imaginary little people in the little cars

scattered around me under the pew,

that they might have nice little suppers,

that they might find nice little friends,

that they might feel safe in their nice little houses.

✶✶✶✶

Willie Edward Taylor Carver Jr is an author and advocate. He is the 2022 Kentucky Teacher of the Year. He holds a B.A. in French and in English, an MAT in French and in English, and a Rank 1 in French Linguistics. He is currently finishing a Masters in Fine Arts at the University of Kentucky. Willie’s story has been featured on ABC, CBS, PBS, NPR, and in The Washington Post and Le Monde. His advocacy has led him to engage President Biden, and to testify before the United States House Subcommittee on Civil Rights and Civil Liberties. He is a board member of the Kentucky Youth Law Project and the author of Gay Poems for Red States.

✶

As a Bookshop affiliate, Another Chicago Magazine earns a percentage from qualifying purchases. This income helps us keep the magazine alive.