Summertime, and we all stood out in front of the house to say goodbye to Uncle Harold. We called him Uncle Ham, a nickname leftover from his childhood with our mother spent in the town he was now leaving behind. In favor of San Francisco. For warmer weather, for what we all imagined was a life of beaches, palm trees, and dinners with celebrities. A perpetual summer with beautiful people who all knew our uncle by name, welcomed him into their homes, their swimming pools, and their fancy cocktail parties that began at the golden hour of the day and ended well after the next one had started.

In Michigan, he was leaving behind his little apartment above the hair salon where he worked styling the hair of ladies in the town or cutting ours when our mother brought us in. From his apartment, he sold whatever he could: winter clothes, furniture, his favorite lamps he’d bought at a roadside antique shop up north. His Rambler coupe went to a young high school girl. Both Emily and I were too young to drive.

With that, he had enough money to leave.

When Uncle Ham told us, all of us were upset. Our mother couldn’t understand why her only sibling would leave behind her, their mother, his niece, and me, his nephew. There were Sunday dinners, trips to the drive-in, vacations at the lake house, and a helping hand nearby if he ever needed it.

He told jokes, sometimes swore (especially about Goldwater), played The Stones or Aretha Franklin in his car when he drove us to get ice cream or buy us clothes. He lightened rooms, turned banality into levity.

But for Uncle Ham there were snowstorms, bars that shut down before ten pm, and fewer and fewer friends up for parties or weekend getaways.

Harold was thirty. This was The Sixties.

We stood out on the lawn before the dew had dried up and watched Uncle Ham slide two suitcases into a yellow cab. He kept his eyes averted until he finally had to face us. Our grandma could not stand to see him off, so we hung there, the three of us, like ghosts from his soon-to-be past.

“I’m sorry,” he said to us. He had longer hair, a polo shirt that emphasized his skinny appearance, though our mother always fed him so much. He was older than us but still young. His face had a look about it, as if to say, is this right?

He fought tears until the moment the taxi drove off. We watched him go, his face a regretful smear through the dirty window. At the last possible moment, he held up a hand to wave.

Wordlessly, our mother took us to school—our prison—while Uncle Ham went on to the land of milk and honey and sunshine and oranges. For many months, our home felt heavier. Like a house boarded up for winter. Like a house whose party has moved on down the block to a newer and better party, leaving behind the wreckage of what might have been.

✶

He called on Thanksgiving that year. With the turkey lying gutted and cavernous in front of us, we passed around the telephone quickly, as long-distance charges ticked away. The phone came to me last.

“Mitchell, what’s shakin’, kid?” He sounded like he was in a hotel or some place with many voices in the background.

“The turkey was dry,” I told him.

“Your mom should have gotten a ham, like I always tell her.”

“So you could make Ham-eating-ham jokes?”

He laughed. “Listen, Mitch, I’m coming home for Christmas.”

“I heard.”

“At least show a little excitement!”

“I just spat out Grandma’s ambrosia salad in surprise!”

“Yeah, I always did too,” he said with what I can hear is a disgusted frown. “I miss you kids.”

“Then why did you leave?”

“Ouch, right in the kisser.”

“Don’t say, ‘someday you’ll understand, kid.’”

He pauses. “Someday you’ll understand, kid.”

✶

Mom and Uncle Harold never knew their father. He was mostly absent after Harold was born. There were shades of him in their early lives—memories of him killing a garter snake in the yard or fixing things around the house. Once, on his way for a visit, he’d run into an old friend from college and gone off drinking instead of taking Harold and Mom to the state fair. He showed up two days later, hungover, and gave our grandmother a wad of bills. That was the last time they saw him.

Grandma raised them herself. We called her Marnie. She was a Danish immigrant who’d come over alone at fifteen on a ship piloted by the same captain who would later go down with the Titanic. She was a typist, a maid, a bartender, a cook, a secretary, and, briefly, a backup singer for Bing Crosby.

During night shifts, she left Harold and Mom to take care of themselves. Sometimes they were frightened by outside noises, so they stayed awake talking, making up mystery stories, or recreating radio programs. Little Harold was always the star; he was always “hamming it up.” They started calling him Ham. The name stuck.

But history repeated itself too. Maybe our mother saw some resemblance of her own father in ours, and maybe her brief marriage to him was an attempt to finally encase that kind of wayward man in a home with two cars, a dog, and coffee in the evening.

He left when I was four, Emily six. He left us with vague memories of missed school plays, scotch and sodas, and a lot of yelling at missed fly pop-ups on the baseball field.

So Uncle Ham stepped in. He did Emily’s hair before plays, tied my tie before my first Communion. Encouraged me to read or take up music instead of ball games. He talked to us when President Kennedy was shot. But when he left too, the cycle seemed to be continuing.

✶

The last day of school before Christmas vacation comes like a parole hearing. Summer has hardened into winter. It feels like we have never left school since the day Uncle Harold left. We feel older; Uncle Ham feels distant. But finally, the hour of his return, the hour of our freedom approaches.

The clock hangs like a far-off moon in the corner of the classroom. Like a halo over Timmy Pollack’s head. He looks up and gives me the middle finger as we listen to long rambling arcs of math problems. Seventh period.

In idle moments, in between glances at the clock, I stare at the faces around me. Up close, I know their fading freckles or their bouts of acne, which cast them out like lepers from the colony. I know when they’ve gotten a new haircut, even the ones who had to switch barbers when Uncle Ham moved away. Even without looking, I know what some of them are thinking about me, what they’re saying, like I’ve been trained in lip reading for an episode of Mission Impossible. I’m an infection in their blood stream.

Timmy Pollack has golden hair and blue eyes. He likes many girls, and they like him back. He guards the clock and sees every time I check it. Maybe he’s docking it on his notebook. He knows. I think they all know. They all know how many times I’ve looked at the clock and how many times I’ve looked at Timmy Pollack.

School empties and kids fumble out into the nearby hills, recently covered in snow. They slip and sled home.

Emily has taken up smoking and stands with three of her friends in the same knee-high boots, all shivering and exhaling at the top of the hill. This is where we meet every day, looking down on our little town, nestled in snowy hills like it’s been cross-stitched onto a throw pillow by the kindest grandmother in the world.

But it’s mean sometimes, so Emily waits for me everyday to escort me home like the Secret Service. She wants to get home today to be there when Uncle Ham arrives.

“Why are you late?” she asks, flicking her cigarette away like a pirouetting snowflake.

I study the hill sweeping down from our feet. It’s perfectly slick. You might reach the bottom and never stop going. “I took the long way.”

She knows what this means, knows I waited in the bathroom for the exits to clear. “Alright, I gotta jet,” she says to her friends.

Kids tumble and slide all around us on stolen lunch trays. They are more joyful than usual, newly free.

“Do you want me to push you down?” Emily asks.

“On what?”

“Your bony little ass.”

“Fuck you.”

She doesn’t reply for a moment as we walk toward home. “Sorry,” she says.

✶

Uncle Ham is home, but he’s not there. His bags are in the guest room, but not him. Just Mom, who’s come home early from her job as a clerk at city hall to clean the house and bake cookies. She’s in the kitchen covered in flour and listening to Johnny Mathis sing Christmas carols.

“He went into town to make a call,” she explains.

“Why didn’t he do it from here?” Emily asks.

“It was long distance,” Mom answers. “He had to call home.” The way she says home feels insulting. This was supposed to be his home. This is our home; it should be good enough for him too.

Mom turns her wrist and sprinkles tumble onto a pan of sugar cookies. I watch her, transfixed for a moment. Emily disappears into her room and tries to drown out Johnny Mathis with Jefferson Airplane.

“How was school?” Mom asks.

“The usual.”

She stops to look up at me and offer a careful smile.

Uncle Ham’s door is ajar. On his bed, his suitcase is open. His shirts have been folded into neat little squares. He’s brought a pair of moccasin slippers that sits waiting on a foot stool. His suit is hung up on the closet door, a red Christmas tie uncoiled to the floor. Mom has put a double picture frame on his nightstand with our most recent school portraits. Beside them: a black-and-white photo of Mom and Uncle Ham as kids at the lakehouse up north.

✶

Johnny Mathis and Grace Slick fight it out for a while, with me in between. I pretend to be asleep when Uncle Ham knocks on my door. That angry sleep you do when you want an adult to apologize to you. I can tell Emily is angry too in the way that she moves to the Kinks to Jimi Hendrix with barely a hint of changing records.

Sometime later, the music stops. Through the walls, I can hear Emily talking to Uncle Ham. She sounds happy. I can’t hear exactly what he’s saying, but I know it’s not patronizing. Nothing about how old she’s getting, or how her grades are impeccable like always. He talks to her like an equal. He has a way of making people feel like they are the most interesting person in the world.

✶

To make amends, Uncle Ham takes us out that evening for pizza. He holds court in our booth, sometimes stopping to shake hands with people whose hair he used to cut or style in his long-ago lifetime here in our simple town, where pizza is a delicacy.

There’s an enviable ease to him suddenly, as he slopes back into his seat, watching us eat and drink our fill of pizza and Coca-Cola.

“What are you guys listening to these days?” he asks us.

Mom scoffs. She hates the rock music that’s been shaking her house lately.

“Well, everyone loves the Beatles,” Emily says, as our spokeswoman. “But I love a band called Big Brother and the Holding Company. I want to be a lead singer like Janis Joplin. She’s going to be big.”

“Mitch, what do you listen to?” Uncle Ham asks.

Neon light from a Pabst sign reveals our uncle’s entire face. I can see the stray pockmark on his right cheek from a case of chickenpox that nearly killed him as a boy. The start of a jetlag beard is outlining his mouth and chin. He’s tan, airier, like he’s actually been on vacation all these months and wants to tell us everything.

“I dunno,” I say. “Whatever’s playing.”

“C’mon, man,” he says. “You have to have your own music.”

I shrug.

“He likes when I play Judy Garland or Perry Como,” Mom says, pulling me in for a hug. I pull away quickly.

“I like James Brown,” I reply.

Emily scoffs now.

“I like how he dances.”

“Right on, soul brother,” Uncle Ham answers.

“I don’t know how you keep track of all this, Ham,” Mom says. “All the different musicians. British ones, American, then the movie stars.”

“You just gotta come to Hollywood.”

“You live in San Francisco,” she replies.

“Everyone’s famous in California, lady.”

“Have you met any celebrities?” Emily asks.

“I saw Robert Vaughn crossing the street once.”

“Wow,” Emily replies with rich sarcasm.

“Trust me, kiddo,” he says, “when you guys come to visit me, we’ll find all the stars.”

Uncle Ham makes another call before we head home. Emily and I watch him from a table where we hold leftover slices of pizza in tinfoil swans. Mom is in the bathroom.

“Who do you think he’s calling?” Emily asks.

“Work? I dunno.”

“What kind of emergency could a hair salon have?”

“Ran out of shampoo?”

She socks me on the arm gruffly.

“I bet he’s got someone out there,” she adds.

“Like who?”

Shut inside the payphone booth, Uncle Ham has changed like Superman back into Clark Kent. He seems bent, smaller, and his motions less nimble.

“Maybe he’s in the mob,” she says.

“We’re not Italian.”

“There are others—Italian, Russian, Japanese.”

“We’re not any of those.”

“Where’s your imagination?”

✶

Christmas Eve Mass the very next day feels like the final obstacle in a mythological quest. Our reward for sitting through the service is Christmas dinner and presents.

Mom still prays and expects us to as well. Because we are at the age when our free will is burgeoning, we oblige her. So does Uncle Ham, who stands in the hallway of the church, tying my tie like old times.

“Looking dapper, if I say so myself,” he mutters as he pushes the knot up to my chin. “So who’s the prettiest girl at school these days?”

“Me,” Emily says, silhouetted by a life-sized manger scene.

Uncle Ham looks me in the eye. “Or at least, the prettiest to you.”

I feel myself sweating in my shirt suddenly, searching for a name to give him like a suspect looking for an alibi.

“He likes when the boys get girlfriends on My Three Sons,” Emily offers.

Uncle Ham laughs.

“Especially Robbie,” Emily adds. “Whenever he gets a girlfriend, Mitch pays attention. Robbie gets all the prettiest chicks.”

“She doesn’t know anything,” I say hotly.

Uncle Ham straightens his own tie. “I didn’t mean to make you feel awkward, Mitch.” He pauses. “No hard feelings?”

“Who were you on the phone with last night?” I ask him.

He smirks, then tugs on my tie one last time so that it’s too tight. “Perfect!”

Father Angelo rambles on about Bethlehem and prophecies and flocks of sheep. Mom listens intently, though even she glazes over time to time. Emily studies her nails or picks lint from her skirt. Uncle Ham tries to make me laugh by pretending to doze off, until Mom elbows me and shoots us a glance.

I recognize faces from school in the crowd. Truly, I did not want to think about any of them until the new year. The girls are in their very best dresses, hair held back with headbands or ribbons. The boys have smoothed out their rough edges into their finest suits, some of which they’ve started to outgrow.

Timmy Pollack is there too. He sits between his two older brothers, who are both on the high school football team. They are stoic, quiet templates for what Timmy will become. He’ll inherit their oblong chests and their neck muscles that go taut when they turn to see something or their blue eyes that portend something biblically forbidden.

When he sees me, Timmy gives me the finger again. His brothers turn to see me, and all three laugh. I pretend I haven’t noticed.

Uncle Ham, though, has seen the whole thing. I look up at him, but this time, he has no funny grin. He’s blank, hovering on something you might say is worrisome.

Sometimes you think you know a person. You think you’ll know what they’re feeling. I realize I don’t know what Uncle Ham has been thinking or feeling for a long time. California has weathered him with sun and heat. Michigan has begun to change me, too. We’re two birds, one gone away for winter, one left behind in the cold, but both singing variations of the same song.

Sometime after the sermon, Uncle Ham gets up and doesn’t come back. We look for him after mass, but he’s not out in the hall by the manger, not at the car, not anywhere.

Mom drives through town, pausing at bars mostly, though all of them are closed for Christmas. Emily and I press ourselves to the windows, studying each face wandering through the snow. We can see into houses along the way, the big Victorian mansions where long tables are encircled by whole, intact families. Lights lap around the walls and windows or shimmer deeply under velveteen blankets of snow. Cars pull up, and more children pile out.

We have no father. We have no cousins. Just our slightly religious mother driving her two kids around, in search of our flighty uncle.

We find him at a phone booth outside the drugstore. He’s having another phone conversation.

“Who’s he talking to?” Emily asks.

“California.” Mom studies her brother through her headlights as he finishes his call and collects his change.

“The whole state?” Emily mutters.

Uncle Ham steps out from the booth and rounds the car to the passenger side. “Sorry about that,” he says when he gets in. “Thought I could make it back in time. I’m starved!”

None of us ask about the call.

✶

Marnie comes for Christmas Eve dinner. She smells regal, like a dowager, like things washed and dried in sunshine. She gives us each a wet kiss. When she comes to Uncle Ham, she stops.

“Hammy,” she says with her vague Danish accent. “I missed you so.”

“Hi, Marnie,” he says. “Merry Christmas.”

“Glædelig Jul,” she says in Danish. “You’ve been gone too long, Hammy.”

They walk arm in arm to the dining room, where Mom has made magic with her pittance of a salary. She learned it from her own mother, who no doubt learned it from her own back in Hjørring, on the sea. Our family’s Christmases are homespun, thrifty, effervescent. A long line of grandmothers has buoyed us with traditions and recipes, and erased the men who have chosen to be absent.

Uncle Ham’s is undoubtedly an absence too. There is bitterness, but there is a momentary feeling to it too. At least to us. He’ll find whatever he’s looking for and come back eventually, we think. Or maybe someday the sun will find us too.

“You look skinny,” Marnie says sweetly. “You need a woman to cook for you.”

“I eat plenty.”

I feel like we’re eavesdropping, as our grandmother and uncle reunite in the Christmas light.

“Who’s feeding you, Marnie? Huh? You have a new man?”

“Stop it,” she says, laughing. Then like Greta Garbo, she coos, “Oh Hammy, why’d you leave us?”

Emily sneaks us both a few sips of gammel dansk brought over by Marnie. The adults are tipsy enough that they don’t notice the bottle is getting lighter. The two of us listen, red-faced and bleary, as the adults reminisce about old Christmases. Marnie talks about an old neighbor who brought them oranges on Christmas morning, when they had nothing else. Mom and Uncle Ham remember a Christmas Eve with Grandma when the fire department came after the tree caught fire, lit by actual candles at her insistence of Scandinavian traditions.

Later, Uncle Ham perches himself at the old stand-up piano and starts tinkering out Christmas carols. Mom joins, Grandma sings Danish lyrics, and even Emily, secretly sloshed, goes over. For a while, we look like the cover of a Christmas card, the TV movie of the week.

“Hammy, play something else,” Marnie says sometime after the tenth or eleventh carol.

“Now taking requests,” he says, shaking an ashtray for a tip plate.

“You know what I want to hear,” she says bashfully.

Uncle Ham starts playing an old tune from before we were born. We’ve heard it before, though. Grandma heard it at a cabaret once and sang it to her kids, and they sang it to us:

“What does it matter if rain comes your way?

And raindrops patter all day?

The rain descending should not make you blue,

The happy ending is waiting for you.

Take your share of troubles

Face it and don’t complain

If you want the rainbow,

You must have the rain.”

Beside the aluminum tree, we open presents. Marnie gives us each ten dollars in a greeting card. Mom watches us open new boots and new razors—me for my wispy mustache, Emily for her patchy legs.

At the end, Uncle Ham gives us kids a package wrapped in brown paper. Emily opens hers first: out of a box tumbles a small, polished rock that looks no more unique than one you’d find in a yard or kick up the street on a summer day.

“It’s coal, how fitting!” I say, suddenly more enlivened by alcohol.

“It’s a meteor,” Uncle Ham says proudly. “It came from space!”

“Just like Em,” I say.

Emily socks me on the shoulder.

“Thanks,” she says.

In my hands is a thin, square package in the not-so-secret shape of a record. I unwrap it and see James Brown’s face in front of me.

“Wow, thanks, Uncle Ham.”

Sliding the record out, I realize it feels thicker than usual. The adults and Emily have moved on to something else, while I look closer. Behind James Brown is another record: Judy Garland.

✶

The household wakes up in a collective, yet unspoken hangover on Christmas morning. Mom has found her way into the kitchen to make a feast of eggs, bacon, and chocolate pancakes. The pot is full of coffee. Even milk for cocoa is bubbling on the stove.

I wake before Emily and go to the kitchen. Mom hums some vague Christmas song. For a moment, she doesn’t even notice me there. Recently, I’ve wondered if she’s unhappy. But she never says anything about it. Maybe she’s happy sliding chocolate pancakes onto a plate and seeing her brother, her best friend, once every few months.

“I didn’t see you there,” she says. On her way to the table, she kisses me. “Merry Christmas, Mitchell.”

“Merry Christmas.”

She stops on her way back to the stove. “You look different.”

I frown. “I’m taller than Marnie now. Is that it?”

“No, that’s not it,” she says. “Something else.”

She sends me to wake the others. By which, I throw a pillow at Emily to wake her. She grimaces through her hangover.

“Is there coffee?” she asks.

“Since when do you drink coffee?”

“Since you started being such a shithead.”

I turn away to wake Uncle Ham.

“Mitch?” Emily calls after me. I stop. “Merry Christmas.”

Uncle Ham is already awake. I can hear a low voice in his room. So low that I barely recognize that it’s actually him.

“Uncle Ham?” I ask.

He doesn’t hear me. At the doorway, innocently, I listen to his conversation.

“I don’t care about the charges,” he says to someone. “I’ll pay my sister back. I miss you. I had to hear your voice.”

Uncle Ham fills the room with wanting. But there’s desperation and some betrayal too. There’s someone else he loves more than Mom, Emily, me, maybe even Marnie. His voice sounds young, almost childish—he’s pendulumed between seeming young and seeming old so many times in the last few days.

“I don’t know how much longer I can stay,” he murmurs. “It feels so wrong to be without you on Christmas.”

I’ve never heard Uncle Ham’s voice like this. He’s always been confident, indefatigable; he sounds jaded, wounded, famished. And maybe that’s what wanting is. This mystery caller holds a different place in his life than any of us.

“Mitch?” Uncle Ham says in a normal voice. Then quickly to the caller, “I have to go.” I realize he’s seen the two shadows of my legs underneath the door.

“Breakfast is ready,” I say through the door.

Uncle Ham hangs up. “You can come in.”

“Mom made a big breakfast,” I say, pushing open the door.

He stands up and starts folding his clothes, making his bed, putting everything in order like it always seemed to be. “I was just on the phone with a friend.”

“There’s bacon.”

“I can smell it,” he says with a flat smile.

I turn away to go back to the kitchen.

“Mitch?”

He’s looking at me from across the room. I don’t want to hear what he’s going to say next. I can tell: he’s never coming back.

“Are you having trouble in school?” he asks.

I hesitate. “My grades are okay. Emily helps me with math—”

“Not like that,” he says. “I mean, with the other kids. The other boys.”

“Everything’s fine. Some of them are just stupid.”

“That’s an understatement,” Uncle Ham replies, nodding. “I had trouble too. But you know, it’s not always going to be like that. It took me a long time to realize it. I’m not saying it’s perfect by any means, Lord knows. But…” he searches for the words. “You should know, Mitch, that whatever you decide, whatever you want to do, whatever you like, there’s a place for it. Might be here, might be California. There are lots of places, Mitchell, where it’s easier. You can find them.”

For a long minute, I stand there, unsure how to reply. “Okay,” is the standard response for a kid whose adult suddenly seems assuredly less adult. “We should go. They’re waiting.”

Uncle Ham nods.

Emily and Mom look up to see me standing there. I’ve brought Uncle Ham, who smiles and sits at the table where Mom begins to dish out breakfast. She scoops out piles of the yellowest scrambled eggs, ribbons of bacon, toast that’s perfectly browned, all while humming the same song.

Uncle Ham is the quietest he’s been in days.

Mom sits and begins eating alongside Emily. Uncle Ham has still not moved.

“What’s wrong?” Mom asks him. “Aren’t you hungry?”

Uncle Ham pauses regretfully and takes her hand. “I have to go,” he whispers.

“What?”

He nods.

Mom starts to cry tears she’s been saving up for his inevitable departure. Emily’s eyes redden with her own tears.

“I miss you,” Mom says.

“I know,” Uncle Ham responds. “I love you all.” He squeezes her hand. “But I have to go.”

✶

Wintertime now, and once the arrangements are made, Uncle Ham packs up. There isn’t much to do; he lives out of his suitcase where everything is folded and arranged elegantly. He never bothered putting anything away, because this isn’t home anymore. It’s a waystation.

Once again, a yellow cab pulls up to the house and waits outside as we say our goodbyes.

Mom hands him two sandwiches in cellophane. He kisses her on the cheek. “These’ll be gone before I even get on the plane.”

He turns to Emily next. “I didn’t get to cut your hair, baby doll,” he laments. “You don’t need me though. You’re figuring out who you are already.” He runs a finger over a strand of her brown hair in admiration. They hug tightly.

When he comes to me, he quips: “And I think I’ll miss you most of all, Scarecrow.”

“Shut up!” Emily says.

He puts a hand on my shoulder, looking at me, man to man. “You can call me whenever,” he tells me. “It’s only long distance.”

When he’s gone, there’s that feeling that Christmas is over, which is actually the case in our situation, so the feeling is double. The house is quiet.

The three of us stand in the front room, looking around with new eyes. All of us land on the piano in the corner. The stench of bacon is still thick from the morning.

“I think I’ll go for a drive,” Mom says. She hurries out of the room before having to invite us.

Emily turns to me. “Wanna go sledding?”

✶

The hill has gathered a swarm of kids. Maybe their parents have kicked them out of the house to burn off the Christmas cookie sugar. Some of them have brand-new sleds they want to try out.

It’s a clear day, and everyone has come outside like Charles Dickens and Norman Rockwell have had a love child.

At the top, Emily and I look down the white slope before us. Kids we know are climbing or tumbling around with their siblings or cousins. We just have each other.

“Hey! It’s your boyfriend,” someone says to Timmy Pollack nearby.

We look over to see Timmy as he punches whichever one of his goons has just piped up. They’re all crowded at the top of the hill with us.

“Oh, for fuck’s sake,” Emily says loudly.

“Don’t worry, Mitch,” another kid shouts. “We’ll be back in school in no time, so you can jerk off at your desk again.”

“What do you jerk off to?” Emily snaps. “Your sister’s fat ass?”

The boys howl and knock into each other like primates.

“I’d rather have a fat sister than a faggot brother,” another says.

“Alright, you fuckers!” Emily says, throwing down our sled and taking off her gloves.

“Em,” I say, stopping her. “I got it.”

The boys bristle as I approach them, stepping around Emily and crunching gingerly through the snow to meet them there at the top of the hill. I come upon Timmy Pollack, whose face I can see closer than I’ve ever seen before. He’s not as handsome up close.

We eye each other for a long time: him, waiting to see what I’ll do, thinking there’s nothing I can do; and me, looking simply into those blue eyes of his.

So I kiss him. No one knows what to say or do; they just stand and watch. It’s not a long kiss, but not a quick one either. Our mouths are jammed together like couples in the old movies. There’s a wetness, a hardness, but nothing memorable, nothing that I’ll think about someday with wistfulness, with wanting.

We break free, still staring at one another, and that’s the end of the crush. Because a crush is all it is.

Instead, I take the sled and go to the precipice of the hill, its long stretch an obstacle course of other kids or spinning sleds or divots in the ground. But I launch myself flat onto the hill and slide freely all the way down.

✶✶✶✶

David Nelson is a writer in Chicago. His short story, “Tusk,” was published by Rappahannock Review and received an honorable mention from Glimmer Train for the August 2015 Short Story Award for New Writers. Another short story, “Superior,” appeared in the January 2018 issue of The Tishman Review and was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Most recently his short story, “Khodynka,” received an honorable mention in Glimmer Train‘s final Family Matters contest. His true crime book about the victims of John Wayne Gacy, Boys Enter the House, will be published in 2021 by Chicago Review Press. He also works as a project manager for an e-learning company in Evanston, Illinois, where he completed his master’s in journalism at Northwestern University.

David Nelson is a writer in Chicago. His short story, “Tusk,” was published by Rappahannock Review and received an honorable mention from Glimmer Train for the August 2015 Short Story Award for New Writers. Another short story, “Superior,” appeared in the January 2018 issue of The Tishman Review and was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Most recently his short story, “Khodynka,” received an honorable mention in Glimmer Train‘s final Family Matters contest. His true crime book about the victims of John Wayne Gacy, Boys Enter the House, will be published in 2021 by Chicago Review Press. He also works as a project manager for an e-learning company in Evanston, Illinois, where he completed his master’s in journalism at Northwestern University.

✶

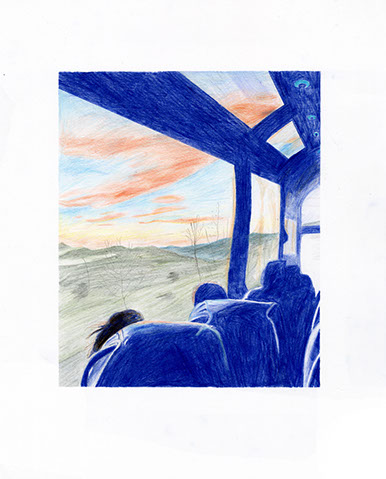

John Grund is an artist based in Savannah, Georgia. When he’s not drawing, he can be found wandering the woods or basking in the sun. John primarily works in comics, but does editorial illustration and storyboarding as well. His work focuses on getting big ideas into little stories. He’s open to in-house work, visual development, concept art, or anything in between!

John Grund is an artist based in Savannah, Georgia. When he’s not drawing, he can be found wandering the woods or basking in the sun. John primarily works in comics, but does editorial illustration and storyboarding as well. His work focuses on getting big ideas into little stories. He’s open to in-house work, visual development, concept art, or anything in between!