It was George Harrison’s “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” that did it for me as a kid.

I was only five years old when I left the city. My memories of Medellín are like floating embers, sparks that go off in my mind whenever I am at work, eating lunch, or driving down into Elizabeth, New Jersey, to visit one of my many cousins. These memories are all just mashed up and whirled together into smells, voices, trips to parks, pools, and the occasional bullets grazing the neighborhood bricks or gunning down a neighbor on his way back from a morning milk run. As a child, before moving to New York, I lived in Itagüí, a municipality within the Medellín metropolitan area. I was born in Itagüi’s Seguro Social hospital, the same building where many men and women were rushed daily during some of the worst moments of the war, when many intellectuals and politicians were exterminated by the Colombian government and the same drug suppliers funded by essentially anyone who thought snorting cocaine was a victimless crime in the eighties. It’s hard to think of familiar names like Kate Moss and Robert Downey Jr. with the killing of little kids and grandmothers, but it’s easy to understand why people ignore celebrities’ role in Colombia’s civil conflict. Come to think of it, Kate Moss’s cocaine habits probably resulted in the deaths of several dead Colombians, and if you extrapolate her industry’s casual use of white powder then most supermodels, designers, and fashion editors have probably buried entire villages of men, women, and children in the mountains of Antioquia. It gives me more reason to pace around my apartment, wondering why I must pay for the consequences of silly people’s decisions, reimagining the times I’ve been stopped at airports and had my luggage searched by the various officers of the world simply because my passport says I was born in Colombia.

Some of my earliest memories as a little boy were the corpses of men laid out in the street like old puppets drenched red and splayed out on concrete while wives and parents and children screamed into the lawless ether. To be born into war, something most will never come to know, to witness the physical manifestation of death before fully understanding its meaning, its weight, its existence as a natural threat, is one of the reasons I sometimes stay up very late in my Brooklyn apartment, sweating and pacing, talking to myself until odd hours in the morning like a man awaiting some sort of final judgment, a kick at the stool under my feet, a tightening of the extended rope attached to the gallows. It’s why I have memorized my medical billing diagnosis code whenever I submit my bill to the insurance company in Omaha, Nebraska (F43.10 – Post-traumatic stress disorder, unspecified, in case you were wondering). But, yes, the Beatles, that’s why we’re here, ain’t it? George Harrison and John Lennon and Ringo Starr and Paul McCartney, well, they had quite an impact on me as a child. I can still smell the covers of the albums, the thick paper, the fresh scent of the vinyl as I took it out and placed it on the turntable. The modern world may be full of corruption and death and totalitarian regimes and it may be composed of both state-sponsored terror and socially revered leaders of Western civilization who post butt pics on social media and sell steaks on the internet, but when the Beatles are around, we can find small wrinkles of hope inside the edges of the madness, between the folds of gravity where we keep our memories in glass jars and in small French boxes composed of pins, bells, and cylinders playing automated music. I found that hope many years ago in Itagüí. I’ve kept these memories with me in the front lobes of my brain like little treasures hidden inside of caves on remote islands.

Medellín is a dreamscape. It’s a parlor show best accompanied with multiple soundtracks. It’s part paradise, it’s part fevered hell, it’s all forms salvation. There is no other city like it, no other location on Earth that has direct access to both Heaven and Hell, where the gates to both are sometimes indistinguishable or perhaps even the same fucking door.

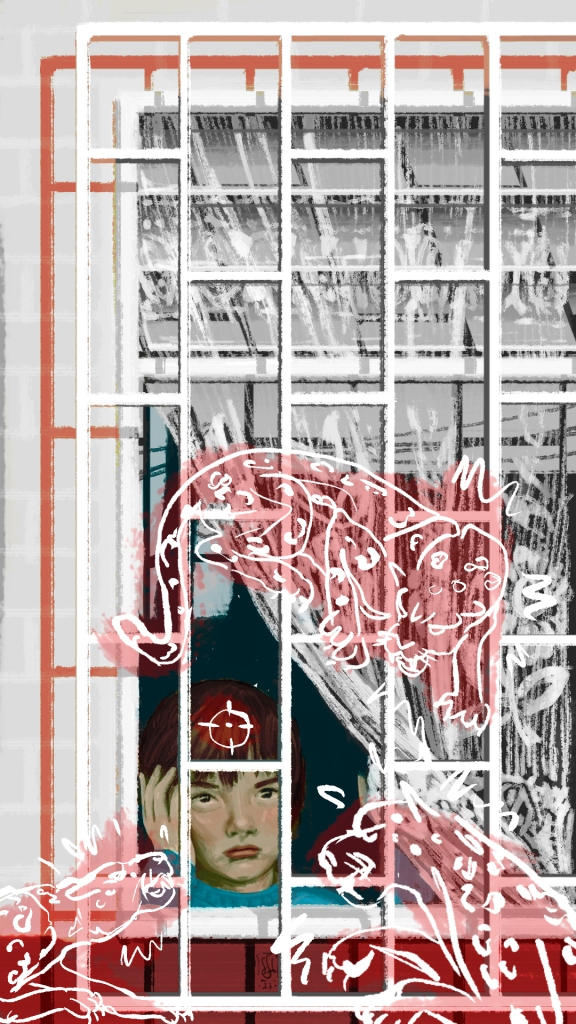

As a child, I wasn’t allowed to leave the house. My grandmother forbade it. As a sign of solidarity, or perhaps curiosity, the kids from around the area would all walk up to my window and greet me through the glass, touching it, placing their hands on it, and leaving behind the sweat and grease of their palms, their small fingerprints captured on the clear surface until my grandmother noticed them and wiped them down with a wet rag. “These children touching the window. Why do you encourage them?” she would ask. Some of the kids were classmates of mine from Jardin Infantil de las Americas, a local pre-kindergarten school where my grandmother would drop me off and pick me up every morning and afternoon. It was the only time I was allowed to play with other children. I spent most of my day at Jardin Infantil cutting out images from magazines, making abstract collages, and painting landscapes and buildings I conjured out of my imagination, often influenced by the 1970s cartoons that played on Colombian television.

I have an older sister; she was fifteen then, but she spent most of her time watching television and did not like to play with me. My family in New York would send us clothing and toys from abroad, and she would eagerly await a new shipment so she could sort through multi-colored shirts, pants, and thingamajigs she could put in her hair. Kids in the neighborhood would call her a gomela, Colombian slang for rich kids who show off fancy clothing and trendy bullshit. My sister would often walk from our bedroom to the front of the house and open the door to paint her nails, sitting on the front steps of our home in bright green or orange, defying the neighborhood teenagers who resented her new clothes and free spirit. Since she was older, she was allowed to sit there, door open, a fresh breeze blowing her long, black hair. I envied her. I was ten years younger, only allowed to interact with others via the window. In school, a group of boys had come to call me windowboy, or El Ventanillas in Spanish, and I would blush a deep bright red every time they yelled it out from across the street. Some of the other children who would come to visit me were just locals whose family knew my family but wondered why I was only allowed to leave when coming and going from school. They would all gather at my window, their faces smiling, passing me little objects underneath a small opening between the glass and the windowsill. I was essentially a child prisoner, forced into this situation by external circumstances no one could control. I had to watch the world from afar, staring out of a hole in a concrete wall and making friends the only way I could: windowpane diplomacy. But hearing about the violence was too much for my family in Queens, and I was too precious to them. The last thing they wanted was a five-year-old child taking a bullet to the head while they sorted out my visa to join them up north.

There was a girl. There always seems to be one, I suppose. She had brown skin and natural blond hair, a common trait in countries like Colombia, Venezuela, and Brazil, a result of hundreds of years of colonization, immigration, and the search for precious vanities like gold, silver, oil, and the fruits that make their way into the morning breakfasts of little children in Middle America. The girl had long, thin arms and rode a white bicycle to my window after all the other kids would leave. She was older than me, almost ten. She would wait until they had all dispersed and left their little notes and toys. I remember her, riding her bicycle, bronzed by the sun, her blonde mop resting over her large dark almond eyes, and her hand placed against the glass, trying to sneak in a butterscotch through one of the slits in the window. Sometimes it was too bulky, and she would mush it up while it passed through the small entrance. And in the background, from my uncle’s stereo system, often played my favorite song from the White Album. After the girl left, I would take the butterscotch, place it in my shorts, and go lie down on my grandmother’s bed. Sometimes I would eat it, sometimes I would not. Sometimes I would forget where I had placed it, and it would find its way into the washing machine or melt inside my clothing after a pair of pants was left out on the patio under the hot South American sun.

I wanted to go outside so badly. I wanted to learn how to ride a bicycle, swim in a river, ring a doorbell and take off running while some chubby neighbor chased me down the street,

or just feel the fresh air hit my face as I played soccer with my friends. Medellín, La Eterna Primavera, or City of Eternal Spring in English, is now a beautiful, sun-drenched tropical playground nestled in the Andes mountains. But in 1989, I was condemned to our one-story brick home with nothing but salsa music, my grandmother’s arepas and salchichas rancheras, and a full collection of the Beatles’ discography that my uncle, who lived in my grandmother’s home, carried around like an ancient tome written by learned elders and smuggled out of Etemenanki in the middle of the night.

George Harrison wrote “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” as an exercise in randomness inspired by the I Ching, one of ancient China’s most sacred written and cultural works. The I Ching, translated as The Book of Changes, provides a philosophical basis for cleromancy, or the belief that a sequence of seemingly random events are a divine will set forth by God or some higher power. Harrison’s song is a response to the world’s chilled heart, its inability to find universal love with itself, with others. Harrison explored modern humanity’s disconnect from its latent tendency to love ourselves and avoid the tribal culture brought upon by modern civilization. He called it “the love there that’s sleeping.” My uncle Julian used to listen to it over and over and over again, which is perhaps why I have its melodic, tearful rhythm so well preserved within my childhood memories. Just thinking about the song and Harrison’s somber voice gives me chills and brings over me that feeling of indulgence and depression that evokes a certain blend of bittersweet nostalgia.

The song, it was fitting for the time—me locked up inside my home, Medellín in the middle of an all-out war between government, rebel soldiers, private militaries, and criminal organizations. Just two years earlier, during a ten-month period, right-wing paramilitaries had begun what was called the “urban defense,” a terror operation led by Carlos Castaño Gil, a former cattle rancher turned drug trafficker who had once worked alongside Pablo Escobar and the Medellín cartel. After a violent falling out with Escobar, Castaño Gil became a vicious right-wing military leader who persecuted anyone with ties to progressive policies or leftwing ideologies. He even had popular support from members of the government, high society, military, and the national and local media. The guitar wept. The whole country wept. Uncle Julian wept because he had lost his fiancée to a bullet several years prior. A man in a motorcycle shot her dead as she walked home from the University of Antioquia with a friend from her political science seminar on World War II and the United Nations. He meant to kill her classmate, a leftist campaign volunteer for a local city council candidate who ran on an anti-corruption platform for a political party called Unión Patriótica, but she caught the bullet instead. Julian never quite got over it. Even after he married, he kept a picture of Victoria in his wallet. Many years later, he moved to New Jersey where he started a home renovation business with his sons. One of them ran for office several years ago and now sits as a councilman in Union City, New Jersey.

My mother’s cousin, Camilo, used to play “In My Life” whenever he would stay at our house on the weekends. Camilo had a pet turtle he would place in his mouth to gross us out. However, my sister and I were never disgusted by the little turtle and our uncle’s antics. Instead, we loved to watch the turtle walk around the patio and find its way through the soap suds and scattered clothing that my grandmother washed every Saturday. I remember the turtle’s little arms trying to find balance, hiding in its shell every time Camilo would pick it up and stroke its belly or its green-and-yellow-spotted shell.

“Stop putting that thing in your mouth, Camilo!” my grandmother would say.

He would laugh and take the turtle out of his mouth. It would walk along his arm, down into the patio’s concrete, and eat little pellets that Camilo would lay out for her. Camilo was a bigger Beatles fan than Julian. He had several vinyl records that he would bring with him to play whenever he came over. Sometimes he would play tracks from Leonardo Favio that touched on topics like love, poverty, children, and nationalism. Favio, who passed away in 2012, is still considered one of Argentina’s most important popular figures. In Colombia, he was a legend and a cultural icon that inspired generations, even those born long after he stopped producing music in the 1970s. After completing his run as a singer-songwriter, he turned to cinema and directed some of the best films in Latin America. Favio would go on to live in exile in Colombia and Mexico because of his opposition to the US-backed Argentine military dictatorship in the late 1970s. He was a contemporary of the Beatles and as big as they were in South America. But he did not enjoy their freedoms or ability to skirt around political controversies. Henry Kissinger had other ideas about Latin American civil rights activists exercising their freedom of speech. Kissinger could kill Leonardo Favio, but he could not kill the Beatles.

Camilo’s favorite Beatles album was Rubber Soul, which is fitting considering his favorite Latin American singer-composer was Favio. Favio’s music makes frequent use of the harpsichord, found in songs like “Al Verte Asi” and “Más que un Loco.” The sound was prominently replicated in Rubber Soul’s “In My Life.” I say prominently replicated because the Beatles’ longtime producer George Martin manipulated a piano bridge to sound like a harpsichord, leading many pop artists to use the instrument in their music during the 1960s and 1970s. Camilo once took us to a public park, another of the clearer memories of my early childhood, and he played “In My Life” on a cassette player while he drove down from Medellín on his way to Parque Comfama Rionegro, a family-friendly public park akin to a cross between a local YMCA and an ecotourist lodge hosting pools, hiking trails, and small children’s activities.

Camilo had served in the Colombian Armed Forces. He had seen firsthand the horrors of war, of the kidnapped, of the disappeared, of the young men taken from their homes in the middle of the night and shot dead because they wanted to fight for a better country. As a soldier, he had been sent to the inner mountains to fight off guerillas and paramilitaries, but the drug war had escalated, and he saw many of his fellow soldiers face the brunt force of modern war, much of it fueled by people in America and Europe enjoying banned substances and romanticizing cocaine like some sort of status symbol that made them feel better about themselves. Where those in the West saw power and joy, he saw young men burned alive with their tongues ripped out of their throats because they said the wrong thing or made the wrong move. But despite the horrors he witnessed, he was one of the lucky ones. Camilo had a prosthetic leg, the result of a roadside bomb that detonated when he stepped over its lever, tearing off his bones and flesh within seconds. In Colombia, these are notoriously known as minas antipersonales, and Camilo was one of the unfortunate thousands that had seen their legs blown off by one of the ugliest weapons utilized by armed groups in the Colombian civil conflict.

The day we drove out to Comfama, I rode a tricycle around a racetrack and my sister roller-skated along a park trail. Camilo watched us from a bench and ate lunch from an unwrapped plantain leaf that my grandmother had packed for him in the morning. Years later, when I came home from middle school after flunking a history exam, my grandmother called my mom to tell her that Camilo had shot himself. He had been living alone and writing letters to a local church asking for forgiveness for some unnamed crime he confessed to committing during the worst years of the civil conflict.

Memories are like phantom jaguars floating around our heads, ready to pounce and scratch and sink their jaws into any smell, sight, or sound that may remind us of their existence, penalizing us for holding them locked inside our minds, deep inside our souls, caged panthers enjoying the meat of time before we, the spectators, watch them tear apart the three dimensions of space like big slabs of cosmic flesh found within the frozen, eerie jungles of our dreams and nightmares. Medellín can be a phantom jaguar; it has haunted me for years, it calls to me as a full-grown man, memories as vivid as bodies I’ve seen riddled with bullet holes in Aranjuez or Robledo. The city, now safer than many parts of Chicago, Los Angeles, or Philadelphia, still carries some of these ghosts that I have had a hard time putting down to rest. As an adult, I have difficulty staying locked up inside my house for too long; sometimes I’ll just get in my car and drive around for hours, refusing to go home. My wife tells me I have “hot feet,” and complains I take off in the middle of the afternoon to random destinations to wander about like some gitano from a distant past. It is hard to explain to her, who is not Colombian, that I was locked inside a house for most of my early childhood, yearning to be free and to live like most children get to live around the world, the way most children live now in Medellín, a city transformed by love and peace and hope and heart.

A couple of months after our trip to Comfama, I sat on the living room couch listening to a children’s song and looking at the album’s cover art while I held it in my hands. One of my favorite records, I had asked my uncle to play it on the turntable. While concentrating on a song about a talking capybara, I heard a tap at the window. I took the album cover, a wild scene of jungle flowers, a large sloth hanging from an avocado tree, and a witch dancing alongside a vulture, and placed it on top of a wooden table directly across from the couch. I walked up to the window and pulled back the curtain. It was her, the young girl with the blond mop and the white bicycle. She smiled.

“Hello,” she said.

“Hi.”

“I don’t have any candy today.”

“Why not? What happened?”

“My father took them from me. He said I can’t give them to you.”

“Why?” I asked.

“He said that he doesn’t like your family.”

“Why did your father say that?”

“He said your father is a communist, and that communists are bad, that I should stay away from this house.”

I looked through the window, my hand gripping the metallic bars that covered them, a common feature in many Latin American neighborhoods.

“Is your father a communist?” she asked.

“I don’t know what that is.”

She smiled and reached inside her pocket. She placed her open palm in front of me.

“Look,” she said.

A butterscotch glistened in her hand. The packaging bounced the afternoon sun off its smooth, clear, gleaming wrapper. She took it with her other hand and passed it through the space in the windowsill.

“My name is Alejandra.”

“My name is Mateo.”

I took the candy from the edge of the window, unwrapped the package, and started chewing it. She laughed. She placed her face against the glass and kissed it. She adjusted her hands on the bicycle and took off down the street. Weeks and weeks went by. I stood outside of the window, waiting for another candy, another butterscotch confectionary. Julian had begun to listen to Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. The cover was wild, frenetic, something different from the half-naked women on the Latin albums that my family usually had lying around. My favorite songs were “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” and “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!” The harmonicas, the organs, the tambourines filled our house with strange sounds and odd words I did not yet know or understand. It was very Medellín in a way that Medellín was not, fully capturing the frenetic energy of Colombia’s economic engine, its fabled city resting in between mountains known to kill travelers for centuries due to their sliding rocks and winding roads full of killer cliffs. The English rock band’s eighth studio album unknowingly, thousands of miles away, encapsulated the same Colombian atmosphere that would go on to inspire intellectuals, rappers, and fashion icons. To borrow from one of my favorite Vince Vaughn lines: the Beatles were so Medellín and they didn’t even know it. My grandmother would ask my uncle to turn the music down and said she didn’t want strange noises played in her house. I liked this album the most and would ask my uncle to play it whenever I felt alone and had nothing to do besides watch cartoons or play with the little plastic toys I would dig out of potato chip bags. Every time he would place the vinyl on the turntable, I would close my eyes and listen to this music my grandmother somehow did not like. But I didn’t care, the music spoke for itself, the room filled with colors, lights, and imaginary friends.

“Do you know who loved this album?” Uncle Julian asked.

“Who?”

“Your father. He used to play this at parties. He always brought his guitar.”

“My father was a Beatle?”

He laughed.

“No m’ijo, he wasn’t a Beatle. Your father was a student at the University. But he also played the guitar. Everyone loved him, and people would gather around him and listen to him play Leo Dan, the Beatles, Juan Gabriel. Era el putas, tu padre.”

“Tio, is my father a communist?”

“Where did you hear that?”

“I don’t know.”

He paused. John Lennon’s voice filled the living room. The Lowrey organ and tambura filled the silence in the room, filled my ears and my heart and the tears in my eyes.

Castaño Gil’s private death squads, the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC), made no distinction between peaceful intellectuals interested in social reformation and their direct rivals, leftist guerrilla groups turned drug traffickers and terrorists. Dozens of professors, students, and people’s rights activists from the University of Antioquia became victims of the AUC and its military leaders. One night, when my father and some of his university friends got together for a jam session, two sicarios, no older than sixteen, pulled up to a private residence near their campus, hopped off a bike, fired a machine gun into a crowd, and took off down the street. My father’s name was on a list that had been distributed around Medellín, a list of thirty-three social activists sentenced to death for crimes against the country. Carlos Castaño Gil and the AUC would go on to murder Colombian citizens for over ten years before his disappearance in 2004. On September 1, 2006, Jesús Ignacio Roldán Pérez, also known as Monoleche (Milky White), a former guerilla and founding member of the AUC, led Colombian authorities to a shallow grave where he had buried Castaño Gil’s bones. The gates of hell swallowed him up the way they had so many before him, leaving behind the organic matter of his bones but binding his soul in chains, transporting it across the River Styx and into the mouth of eternal betrayal.

But there I was, waiting by the window, looking down the street and up the street, staring at the corner store, looking for a sign of long skinny arms, blond hair bouncing on her gypsy eyes, or listening for bicycle bells turning around the corner. As my departure date grew near, the children continued to visit, tapping on the window, asking me when I was going back to school, if I was really leaving, if my family was taking me away. Some said goodbye, others dropped off going-away gifts when my grandmother allowed a small party weeks before I left for New York. But Alejandra, with her blond mop and white bicycle, I never saw her again. I took a butterscotch with me when I boarded a plane on February 5, 1990, at José María Córdova International Airport and ate it on the ride home from JFK to my mother’s apartment on Roosevelt Avenue.

✶✶✶✶

Diego Alejandro Arias is a lawyer, diplomat, writer, and civil rights advocate. He was born in Medellín, Colombia, and grew up in Union County, New Jersey. He served three tours of duty for the United States Foreign Service from 2015 to 2023. He lives fifteen minutes from the Jersey Shore with his wife and three rescue cats, Ricky, Baby, and Miller. He is a member of the Colombian diaspora that fled Medellín in the 1980s.

✶

Sara Serna Loaiza is a Colombian illustrator and designer. Born near Medellín, where she is an architecture student, she freelances as an illustrator and designer. And by personal interest, collaborates with her work on projects related to the diffusion of culture, literature and art, such as revistacronopio.com.