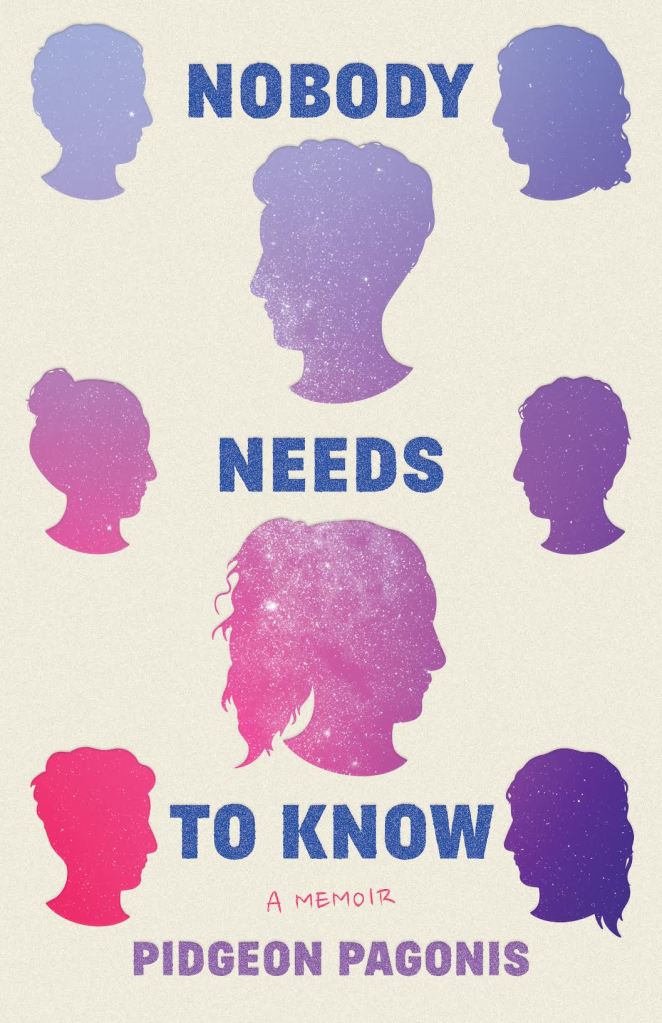

Pidgeon Pagonis is a vibrant author, activist, and presence in the Chicago queer scene. Their new memoir, Nobody Needs to Know, tells their story of growing up in the nineties and aughts, discovering themself as an intersex person, and fighting for the bodily autonomy of intersex children against a paternalistic, abusive medical system. It’s a beautiful account of both painful and powerful moments in their life and a must-read for anybody looking for a book that is vulnerable, welcoming, and, without sugar-coating traumatic events, full of hope. If you’re intersex, if you love an intersex person, if you don’t think you know one, if you’ve never heard of being intersex, or if you’re uncomfortable with the concept of intersex existence, there is something in this book for you and you should read Nobody Needs to Know.

A lifelong Chicagoan, Pidgeon is a writer, filmmaker, speaker, and advocate for intersex children. They co-founded the Intersex Justice Project, which fights against the unnecessary and non-consensual pediatric surgeries used to enforce binary expectations on intersex children. In addition to this critical work, they use their platform to provide educational and support resources to intersex people and parents of intersex children, fighting misinformation, loneliness, stigma and shame.

TOPPLE, August 15, 2023, 235 pp.

ACM managing editor Sasha Weiss interviewed Pagonis on their experiences. The interview has been edited for concision and clarity.

Sasha Weiss: Nobody Needs to Know is such an exhilarating read. When did you first decide to write it?

Pidgeon Pagonis: It was the first few months of the pandemic in 2020, and all my speaking engagement contracts disintegrated into thin air. Suddenly, my income was in jeopardy. Around that same time, I received a call from my friend Joey Soloway. They asked me if I wanted to write a book for their new imprint of Amazon Publishing called TOPPLE. I said yes pretty much immediately.

What was the hardest part to write, and what was the easiest?

Writing it was the hardest part—ha! Writing (or should I say typing on a computer) has always been very challenging for me. I always put off writing essays until the very last minute in school and when I did finally get to the last page, it always felt like my skin was crawling. It’s hard for my brain to sit and focus that long on a screen, and it’s also very hard on my body. I had so many knotted muscles and days of burning dry eyes. It was also super hard on me emotionally. Sitting with my memories like that and going so deep into them while alone was one of the hardest things I’ve ever endured. There were many breakdowns, so many tears, and moments where I thought I couldn’t go on.

The easiest parts to write were the ones that featured other people. I especially enjoyed writing about my softball coach Tommy Thompson because he was such a character in real life that his persona just kind of spilled onto the page. I loved writing dialogue for him and hearing his wacky phrases in my head. I also like writing scenes with my dad. I think I just really enjoy writing the blue-collar Chicago guy archetype because there’s something in those mannerisms and ways of speaking that is both fun to write and feels like home.

You’ve told parts of your story in so many different forms, from documentary to thesis to memoir. How does medium and genre shape the way you share your story?

In grad school for Gender Studies at DePaul, I had an opportunity to choose a creative option for my thesis. I made my first film for my thesis. I was interested in the myth of objectivity and how it often works to discredit people and their experiences. It started out as a memoir, but morphed into a script for a radio piece which then morphed into the short film called The Son I Never Had. It contained archival audio recordings of my family and recordings of my medical records. It also has some photos, video and illustration. Writing the script felt almost like writing short poems.

Almost exactly a decade later, sharing my story again—this time as a book-length memoir—demanded, of course, way more structure and way more writing. There was a team involved. I had a wonderful and amazing writing collaborator named Kenny Poppora, who I adore, and who helped me come up with a structure. Laura Van Der Veer, who I also adore, edited the book for TOPPLE. The book made me go back further and take readers on more of a slow burn through the journey of what it was like growing up as a kid in the dark about their own intersex body, and the ways in which it was being manipulated and mutilated for the sake of maintaining the binary. I sat with these memories during the period of the pandemic when everyone was self-isolating, just reliving them in my head over and over. I had to reenter my body and mind back then and think, what did that house look like, what did that doctor look like, what was I feeling? Whew, it was intense.

One of many moments in the book that made me cry (in a good way!) was your conversation with Lynnell from Intersex Society of North America. The image of you saying “I’m intersex!” in that pizza place feels like a synecdoche of the book. You share so much with your readers, from first crushes, stolen eyeliner and softball games to hospital nightmares and medical lies. How did it feel to write so openly after having been pressured into silence for so long?

I love Lynnell! Shout out to Lynnell!! It felt way harder than I imagined it would. Growing up, I read a bunch of memoirs and life-narrative-type stories from queer authors. I loved how raw and brutally honest most of them felt. I always thought it seemed easy to be super honest while writing your story. The authors made it look so simple. I always imagined that if I ever had the opportunity to write my own memoir, I would be just like them—super honest and raw. But then, when I had the actual opportunity to do so, I found it extremely difficult to do so.

In the end, I worked with Kenny and Laura to write with a balance of looking out for others’ feelings while also maintaining my truth.

Who do you want to read your book the most?

Everyone in my family. And even though I’m super afraid of my mom’s reaction–both because I never spoke to her about so much of what’s in the book (like sex), and also of her feelings getting hurt even though I worked hard to try and make sure that wouldn’t happen. I am looking forward to her reading it.

I also really want other intersex people to read it and be able to feel seen and less alone. It dawned on me recently just how wild it was that I grew up not knowing a single soul who was going through the same thing.

Lastly, I would really like people who were led to believe they need to fear or hate the LGBTQIA+ community, especially trans and intersex people, to read this book. Especially those people working to pass laws against gender-affirming care for consenting trans people, while leaving loopholes for surgeries on intersex kids. I hope they can read my memoir and see the hypocrisy in advocating for laws that will, as they say, prevent trans kids from being mutilated because consensual gender affirming care is not mutilation. It’s life affirming and has a net positive effect for trans kids and adults. It’s only a negative thing when it’s non-consensual and forced on intersex kids who can’t consent.

Though I’ve had surgeries in a very different context, your descriptions of dissociation in medical contexts really resonated with me. Did you expect these scenes would be very relatable to your non-intersex readers as well?

Yes, well not the disassociation in particular but I did have a sense that readers would all be able to relate to the shame aspect. I think many people understand how the surgeons who harm intersex kids use surgery and secrecy to mold us into “normal” boys and girls but what I think is talked about far less is their third tool: shame. Shame does so much work for the surgeons. It’s with us in the doctors’ offices during countless (and usually unnecessary) exams, many of which require our little bodies to be stripped naked and poked and prodded by adult clinicians, preventing us from advocating for ourselves and asking certain questions. It’s with us when we leave the clinic and go back home and to school—keeping us quiet about what we experienced. And I feel like everyone has gone through the negative effects of shame in their life, and I felt like people would be able to relate to that aspect of my medical experiences because it’s so pervasive in almost all of our lives–intersex or not.

What’s next for you as a writer and an activist?

I want to continue my goal, the one I first set my sights on when I first found out I was intersex some 15+ years ago, of ending intersex surgery. I want to keep sharing my story and the stories of others born intersex like me, and spreading those stories far and wide to reach the goal of ending the forced non-consensual surgeries. In the immediate future, I hope to share my first film The Son I Never Had to the public (if you’re reading this and you can help me make this possible–please hit me up) and to complete and share my photography project called Physical Record, which is a collection of black-and-white film photographs of intersex people that I took all over the world some years ago.

I also just want to spend as much time possible laughing, loving, dancing and hold my friends and family as close as I possibly can. I want to heal. No, scratch that, I need to heal. And I want to help others heal too. Healing is foundational to the rest of the work I want to accomplish before I die.

✶✶✶✶

Sasha Weiss is ACM’s managing editor.

✶

Whenever possible, we link book titles to Bookshop, an independent bookselling site. As a Bookshop affiliate, Another Chicago Magazine earns a small percentage from qualifying purchases.