- Early cats

It’s like we were all born under a bad sign, the way my family’s luck with pets went. Of course people at that time were off-their-trolley neglectful as far as pets were concerned. Not like now, when pets are a pampered part of the family. You kids, my mother would say. You never help with anything.

First we had a cat named Topsy. A Siamese with otherworldly blue eyes and an ungodly yowl. Sure, he was annoying and it wasn’t just his name. Nobody could live up to my mother’s standards because we were after all, just kids. She fed him and cleaned his poop out of a cardboard shit box in the basement (way ahead of her time, my mother eschewed plastic) and secretly liked the fact that he swabbed her legs in appreciation when she put a special bowl down for him in the kitchen. She had allergies, she claimed. Hay fever. It was all the rage then. At the slightest sneeze, all the moms claimed hay fever, the greatest excuse ever. Topsy had to sleep skeleton-key locked in the basement no matter how much he cried for companionship, unable to break the basement/first-floor barrier. Later they would discover the brain-blood barrier, the highly sensitive semipermeable border that separates circulating blood from the brain. We lived it first, there in Cleveland. Topsy was run over in a neighbor’s driveway, victim of the free-range pet policy so beloved in the fifties. We would no sooner keep our pets indoors than we would think to put slogans on t-shirts. Our parents called our pets in for bedtime the way they called their kids in for dinner.

Next up was Blackie. What did she look like? you timidly ask. Shut up! It was mid-century Cleveland. She was a tiny wild girl who barely tolerated us. She had kittens that we kept in a big cardboard box till their eyes deigned to open. We gave them away to complete strangers, nice people who came seeking kittens in response to an ad my parents ran in The Cleveland Plain Dealer. Life was so simple then.

Owning pets meant having a plan to care for them even in your absence. My father the professor took a month off every summer and we used to drive places: the Yucatan, the Tetons, the Gaspé Peninsula. My sister and I would have epic fights in the back seat while my parents ignored us. Typically, around the third or fourth day of driving, my mother would “discover” some box of colorful rubbery candy she’d secreted under the front seat, something that started with a “J,” like Jujubes or Jujyfruits. By then we were so exhausted and bored that we’d eat or do anything. It was all carefully calibrated.

While we gallivanted around North America, back home in Cleveland, my parents would have entrusted the care of the latest cat to one of the neighbors for the month we were away. My parents were always friendly with the neighbors, but only up to a certain point. Maybe they didn’t want to be a burden. God knows, being alive was burden enough. We were Jews and it was, in Jewish years, right after the war. After all, we were genetically tweaked to remember for a lifetime. My parents didn’t want anyone knowing our business, because who really knew what might happen next? Everything seemed calm now, sure, with your Levittowns and your GI Bills (in fact my father had gotten his BS, MS and PhD on the GI Bill, beating the quota system that limited the number of Jews at the stellar schools he attended). Sure, everyone loved us now. But the screw might turn again. Another shoe might drop. We hadn’t yet seen those horrific photographs of piles of shoes left behind by victims of the camps, but any one of those shoes could gain agency, seek its disembodied mate, and start a whole world of trouble. We didn’t need anyone to take in the mail for us. My parents had converted the old coal chute on the side of the house to a mail chute and trained the mailman to drop letters and packages through all year round. Voilà! (Or as my dad joked, Viola!) No need to trouble anyone to take in the mail, ever. It was somehow logical to them to leave the cat out for a month too, so the neighbors wouldn’t have to bother going in the house or scooping poop. (What dark Jewish secret were my parents trying to hide? My pre-adolescent inquiring mind wanted to know even back then.) Blackie disappeared during one of our first month-long vacations. Later we saw her about a mile away on the steep hill with the Christian Science Church perched on top that divided Cleveland Heights from Little Italy in Cleveland. My parents made no attempt to bring her or her new batch of kittens home. On the other hand, I became curious about that church which I’d never really noticed before, and later attended a service or two, listening as members offered testimony.

Cats symbolize independence, vulnerability, and bad luck.

- Rats and hamsters

First, we had to learn to love the taxonomy of the unlovable. My father brought home some white rats from what we knew as the “animal house,” in the basement of the university building that housed his lab. The building has long been replaced, with good reason, because my father and so many of his biochemistry department peers died of odd diseases: a handful of early-onset Alzheimer’s, brain cancer, leukemia, my father’s own metastasized breast cancer and unrelated lymphoma. The animal house was an eerie place to visit when I was a little kid. I vaguely remember it being aromatic and underground, maybe a basement or a tunnel between buildings. All the animals were in steel cages, and they were all vocal. Rats, rabbits, cats, dogs, monkeys, all terrified and seeking respite. My father only did experiments with rat livers, and later pig livers that he got from a slaughterhouse, the beginning of his long journey to becoming a pescatarian. He worked with mitochondria for much of his career. But even now I can conjure up the smell of the animal house: fear tinged with feces.

We always had a legacy of giant jars from my father’s lab around the house, usually brown ones that had held chemicals at work that would then get repurposed at home. My parents had both been tiny tots during the Depression and the lessons from those days didn’t go to waste: save everything. One glorious day my father brought home, in one of these giant jars, two tiny white lab rats with red eyes. We rested the clear giant jar on its side to give the rats a smidge more walking-around room. I have no memory of how long these two rats stayed with us. Probably not long enough to be named. But at some point, my mother made tiny chamois vests, ostensibly not for our pet rats but for the ones my father used at the lab. In retrospect, maybe they were one and the same. My father said the vests let him hold the rats in a more comfortable place when he injected them. Did he bring the rats home so she could measure them for vests and we thought all along they were pets? A few years later, when my father had a sabbatical year at Middlesex Hospital in London, he took me to his lab for a day and helped me dissect one of those ubiquitous white lab rats. After poking through its tiny intestines and organs, we shared a bowl of spaghetti at the cafeteria, an inappropriate eulogy.

In my school in London, I was the only Jew. Each morning we gathered to say prayers in the large hall downstairs, standing in some sort of linear formation. It wasn’t a large school, but we all wore dark brown uniforms, the boys in their shorts, the girls in pleated knee-length skirts. As soon as someone higher up in school administration realized I was Jewish, I was banished to the science room during prayer time, and spent that time each morning with the hamsters and gerbils running on their wheels. Instead of reciting The Lord is My Shepherd, I tried to understand why I was being ostracized and what I had done wrong. Finally, I had to acknowledge it was that darn Jewish thing, again.

Rats symbolize adaptability, stealth, and concealment.

- Fruit flies

After the rats, my father brought home fruit flies. Fruit flies are ideal for learning about genetics because they reproduce so quickly. In forty days, adults can lay 500 eggs. We kept detailed notes in the lined composition notebooks my father favored his entire life. Until a few weeks before he entered hospice care, he was still keeping track of every dose of every medication he took for his cancer and the congestive heart failure from the chemo, color coded in his careful scientist’s scrawl.

Down in the basement, we met after dinner to do our experiments. My father wore his white lab coat. It was a while before I realized that the other kids in the neighborhood were not meeting with their fathers to do similar experiments in their basements. Nor did they go on month-long car trips to other countries, or camp out with their families. They didn’t take year-long sabbaticals and come back completely disoriented, either. In my case, sixth grade had passed by while we were away in London. Other important things had happened, too. Everyone learned to conjugate French verbs. Girls learned how to use mascara and curlers. Boys learned how to kiss almost proficiently. Maybe ten or twenty years passed before I learned to recognize other exiles like me, who missed out on basic social graces because of living in other cultures during their formative years.

Fruit flies symbolize perseverance, and not just for their innate qualities: eight Nobel prizes have been awarded for research using Drosophila, or vinegar fly.

- Cats galore

Once we got back from our first sabbatical in England, there would be no more family pets for us as a nuclear family. But after a second sabbatical with my parents, this time in Leeds, I did get another black cat when I returned to university in Philadelphia. I had a second-floor apartment in a duplex owned by MK, an Austrian psychiatrist who had an odd habit of pursing his mouth and whipping his tongue quickly side to side when he dealt with my tall and good-looking roommate, Sheila. Since she was taller than he was, she tended to scoff at his amorous advances, but the fact that he was so much older made his leering come across as creepy. It became creepier still after he went away on vacation and we took a lackadaisical flip through his unlocked filing cabinets in the first floor waiting room. This was way before HIPAA, of course, but still, it was odd that he didn’t bother to lock anything. Inside we found a folder of our odd Austrian landlord as a young man in a Nazi uniform. A short while later, one of his patients escaped a hospital where MK consulted. MK received word that the patient was coming to see him, in the duplex where we all lived. We found out subsequently that instead of informing us that we might be in danger—two young, recent female college graduates in their early 20s—he had immediately barricaded himself in his private apartment on the first floor and left us to fend for ourselves.

But back to pets. My black cat, Lonzo, was named after the Richard Fariña and Eric Von Schmidt song Lonzo N’ Howard. I was partial to the album, as Blind Boy Grunt, aka Bob Dylan, played harmonica and sang backup vocals on a few tracks. I’d gotten this cat as a kitten. She liked to ride my shoulder to classes, and other students gave her lots of attention and affection. Philip Roth was not amused when we got to his class, because as an alpha male he preferred all eyes to gaze upon him.

There was a mouse upstairs in our rental apartment. MK was useless with anything practical around the building, but was determined to set a mousetrap. I joked that Lonzo would probably catch the mouse before the trap could. The mouse’s ears were probably burning, because as we were talking, the mouse scurried right past us. Without even thinking, MK—the probable former Nazi—stepped on the mouse and flattened it. I’ve never seen anything so repulsive. He apologized in his Austrian accent, saying it was instinctive and that he immediately regretted it. Almost twenty years later when my daughter was a newborn and I was a sleep-deprived single mom, I dreamt that I went out with friends to a play and left my daughter alone on my bed, only to suddenly realize, aghast, in the middle of the play, that I had made a terrible rookie mistake. In the dream I made a face that looked like Edvard Munch’s 1893 painting The Scream, a painting I had seen in Oslo while traveling with my parents as a child. I abandoned my companions, raced out of the play and into my bedroom, where my infant daughter was missing from the bed. I searched all over and finally found her in another room on the floor where I had accidentally stepped on her mid-hunt. Now she was flattened as if by a cartoon steamroller. I carefully peeled her up from the Persian carpet. Alive or dead?

Cats symbolize creativity, intuition, and resurrection.

Intermission

A pet is an animal “kept for pleasure rather than utility,” (Merriam-Webster), “a domestic or tamed animal kept as a companion and cared for affectionately” (Dictionary.com). Or that special lucky individual “that someone in authority likes best and treats better than anyone else (Cambridge Dictionary). In my family, we had many attempts at companionship and affection that perhaps fell short, but no one was abused or treated unkindly. We were just a normal family of the fifties and sixties, an era when TV families showed us an ideal that few could hope to achieve: Mothers wore dresses and heels in the kitchen. Siblings never fought. Dad smoked a pipe and brought home the bacon, often changing into slippers and an argyle cardigan with elbow patches to sip his evening martini.

Lassie was a truly extraordinary pet of the time, featured on the eponymous TV show that ran from 1954 to 1973. Trained by Rudd Weatherwax (why didn’t our names sound like that?), Lassie left small children like me agog as he rescued Timmy from one goof-up or another within a strict 22-minute timeframe. That was my memory. In reality, Lassie lived first with eleven-year-old Jeff and his war-widowed TV mom and grandpa. I was probably too young to remember this iteration. In the fourth season, Lassie traded that family in for seven-year-old Timmy and his adoptive parents. There was some churn in the actors who played the adoptive parents over the next few years. Eventually, the producers decided to go for an older demographic, and so the dad took a job in Australia and relocated the family there—everyone except Lassie. Poor Lassie. She joined up with the U.S. Forest Service for seasons 11-16 before striking out on her own for a year and traveling across the country. The series ended with two final years on a ranch for orphaned boys. Often, blacklisted writers wrote the scripts, and during the Forest Service years, scenes were shot in Alaska, Puerto Rico, Monument Valley and Sequoia National Forest. It turns out that the animal trainers got Lassie to turn his head and bark on cue by climbing up on stepladders behind Timmy (or whoever) and waving a chunk of meat at the appropriate time. Though referred to as a “she,” Lassie was in reality always a “he,” a male descendent of the original Lassie. And yet Lassie represented the perfect mother figure of the time: caring, nurturing, rescuing those in peril (especially children), with a demonstrated commitment to family and community.

What a mess.

- Rabbits

My sister is an avid gardener. Every summer she grows a bounty of healthy kale, salad greens, tomatoes, beans, blueberries, currants and raspberries in her front and side yards, and flowers, shrubs and trees in her backyard. Her garden is a very beautiful, peaceful place, with wisteria, a hammock, garden seating in carefully curated outdoor rooms, a large cobblestone patio, and mature trees and shrubs.

Through the family grapevine, I heard that one summer my sister’s idyllic space was marred by an invasion of rabbits. Instead of putting up chicken wire to keep the thieving lagomorphs out—which would change the appearance of the garden—my sister, if one can believe family lore, and I’m not sure I do, was apparently trapping the rabbits and drowning them in a bucket of water. No mollycoddling. How many? One, as an example to the others? No-one knows. Eventually she decided to buy a pair of feral cats which she boarded outside, making short shrift of the invaders. One cat left almost immediately, and the other took up residence under the neighbor’s porch. The rabbits, though, realized their days were numbered, and moved on to greener pastures.

Rabbits symbolize fertility, innocence and lust.

- Dogs

My daughter is crazy about dogs, but I prefer to look, not touch. I’m just not a dog person, I tell her, but I’m slowly coming around to her way of thinking. My cousin told me that all the elder women on our side of the family insisted that they were allergic to dogs and cats, although they clearly weren’t. I can enjoy them from afar. I like their blind persistence, their allegiance, their chatty friendliness.

My mother, in assisted living, tells everyone she is allergic to all animals, especially the ones she meets in elevators. She refuses to allow them near her. How embarrassing, then, that my daughter found an old photo of my mother at around 20, dressed in some sort of short white tennis dress, with one dog on her lap and another with his paw on her leg. My mother was laughing as she caressed them. My mother insists this never happened, and because she is legally blind, we can never confront her with the evidence.

When my daughter was dog-sitting for two black Labs and they were proving a bit unruly, she FaceTimed to show me what she had to deal with. I told her to hold the phone up to the dogs. Using my best mom voice, I said, Sit! Both dogs immediately sat.

Dogs symbolize trustworthiness, loyalty, and guidance.

- Bees

There is a danger that bees will go extinct. Not on my watch. Lola, my current blonde and grey tortoiseshell cat, enjoys hanging out in the garden with me while I tend not only the cultivated flowers: the white, deep pink and blood red peonies, the huge orange poppies with their shuddering stamens, the ethereal blue bachelor buttons, the electric forget-me-nots from my parents’ long-gone garden, Stargazer lilies, toad lilies, Japanese anemones, goat’s beard, Siberian irises, Japanese Hakone grass and climbing roses, but also their wilder brethren: the pale pink queen of the prairie, bottle gentian, many types of Echinacea, sensitive ferns, wild columbine, corydalis, rodgersia, and two varieties of amsonia. To say nothing of the many varieties of black, purple and brown tomatoes, which seem to do best in the limited light of the yard, and the hot peppers, kales and collard greens which likewise are quite forgiving of a lack of full sun.

Both the front and back yards were mostly grass when I bought the building more than 20 years ago, a 2-flat convent owned by an order of nuns headquartered in St. Louis. In its genteel way, the yard reflected both the neighborhood and the sensibility of the nuns. They were aghast at every change I made, from ripping out the filthy wall-to-wall carpeting, steaming off the dreary wallpaper, and removing the 1960s paneling in the sun room on the second floor. When I started slowly digging up the grass and disposing of the begonias and impatiens in the yard, it was as if I’d barged in on their bedrooms, or accosted them while they swilled cheap wine—ample evidence of which I’d find in the garbage cans every few days. In this tangle of animated growth that now surrounds the former convent, my Jewish soul has finally put down roots. My irritation over the nuns’ constant prying about why I had a child but no husband has been laid to rest beside the skeleton of one beloved cat, Frida, and the ashes of another, Wanda. They’re surrounded by hellebores and false baptisia whose roots love exploring the partial shade and sandy soil as much as both cats did. The taproots long ago absorbed the venom, although the memory of it still hovers in the quavering crackles of the cicadas singing their anthem at dusk.

The flowers attract butterflies and dragonflies, which Lola chases, and bees, which she gives a wide berth. They all attack the catalog of flowers like unmanned drones, certain of their targets and the inevitable pollination and procreative outcomes. Life is simple, life is good in the insect world. Eat your hearts out, pesticide companies. There will be none of your encroachment here. Take your squabble elsewhere.

Bees represent industry, wisdom, and good luck.

- Rabbits, redux

Lola, the 20-year-old cat, has been through a medical odyssey the past few months. One by one, she is diagnosed with hyperthyroidism, then a UTI, then a mild kidney issue, then high blood pressure. Her vet patiently tinkers and titrates until Lola perks up and starts regaining weight. She loves to sleep in a cardboard box at night, and to be wrapped up in old hand towels so she looks like a show horse, or Lawrence of Arabia. During the day she plays hide-and-go-seek, or hangs out on my desk while I work.

My formerly chatty mother, now 97, has found a dog she loves, the social worker’s Yorkshire Terrier. She lets him jump in her lap, despite her faux allergies. For years my mother avoided coming to my house because of her fear of encountering cat hair. Some days my mother can talk, usually about the weather, or a cooking show on television. Other days, it’s like trying to rev up the motor on a rusty speedboat, with lots of false starts and abandoned neural pathways.

One day in my garden I notice a dead bird floating in the pond. This happens occasionally, a disturbing occurrence in the fairytale world of tiny, deep ponds. Mine is three feet wide and two feet deep, scarcely more than a glorified bucket, really. Was the bird trying to spear some of the baby goldfish swimming beneath the protective surface of water lettuce and water hyacinth? Did it succumb to West Nile Virus? I’ll never know.

A few days later I am weeding in the garden when I spot a waterlogged, drowned baby rabbit carefully laid out beside the pond. There are small flesh wounds at its shoulder and flank. It looks as if it has been dunked and then gently scooped out of the water. While I’ve found perhaps a dozen dead birds in the pond over the years, this is my first rabbit. My neighbors immediately suspect a feral black and white cat they’ve seen lurking in the alley. But this doesn’t explain why the rabbit appears to be drowned and then carefully pulled out, like a rabbit from a hat.

I wonder if I might find answers on the internet. I find myself going down, please excuse the expression, a rabbit hole:

Do rabbits like kisses?

Do rabbits recognize their name?

Do rabbits get jealous of other rabbits?

How do you assert dominance over a rabbit?

How do you discipline a rabbit?

It turns out that rabbits can die from stress-induced heart attacks, and that getting wet is, for a rabbit, a very bad thing. The more I read, the more likely I think it is that the culprit is a bird of prey and not a cat.

A hawk, then, who I imagine swooped down and surprised the baby rabbit, who tried to wriggle free and perhaps fell into the pond and drowned. Who was then somehow scooped back out by whom? and for some reason laid gently back down, perhaps because the hawk was scared off by a car, a dog, or a person.

How do rabbits say sorry?

Can rabbits die of loneliness?

Time marches on for all of us.

Rabbits symbolize rebirth, resurrection, and incarnation.

✶✶✶✶

Judith Cooper lives and works in Chicago. Her work has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize, Best American Short Stories, and Best American Fantasy. She has been awarded residencies at Carraig-na-gCat, The Hambidge Center, Oberpfälzer Künstlerhaus, Ragdale, The Tyrone Guthrie Centre, and Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, and she is the recipient of several Illinois Arts Council and City of Chicago fellowships and grants. Her work has appeared in New Stories from the Midwest, The Normal School, Pleiades, Shenandoah, The Southern Review, and elsewhere. She is currently working on a short story collection, a novel, and a family essay collection, of which “Family Pets” is a part.

✶

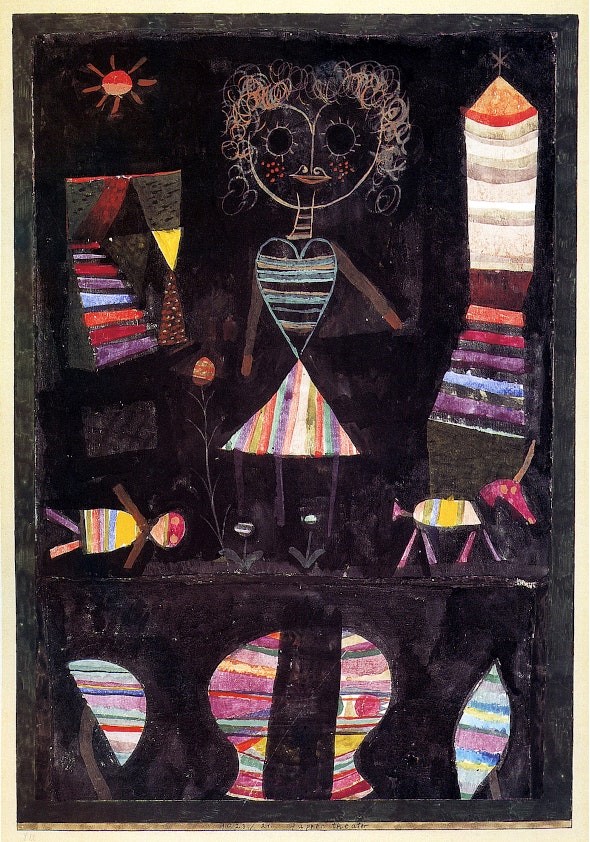

Paul Klee (18 December 1879 – 29 June 1940) was a Swiss-born German artist, influenced by expressionism, cubism, and surrealism. Although he was a draftsman, he explored color and wrote about color theory, and his lectures on this topic are held to be as important for modern art as Leonardo da Vinci’s were for the Renaissance.