Interview by Tamika Thompson

In the summer of 1969, it was illegal in most states to be gay. In New York, same-sex public displays of affection were against the law, as was wearing more than three pieces of clothing intended for the opposite sex. Members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender communities were often harassed on the streets, and police routinely raided nightclubs where they congregated.

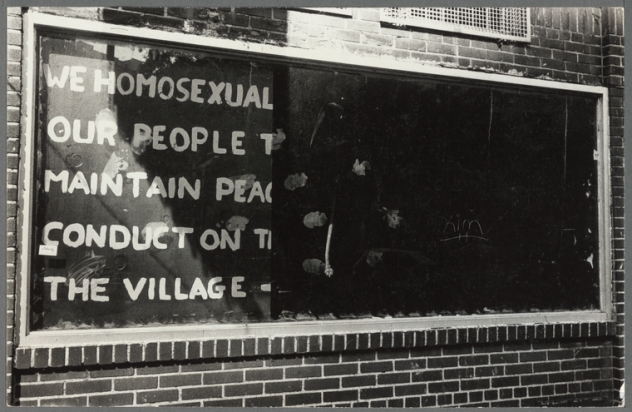

The mafia, looking to make money off of the marginalized groups, stepped in and opened the Stonewall Inn, a gay club in Greenwich Village and one of the only nightspots that allowed dancing alongside its watered-down drinks. The raid on June 28, 1969, was not the first at Stonewall, but that early morning surprise visit was the one that ignited a riot.

Police roughed up and arrested patrons, and, for six days, Village residents and Stonewall frequenters clashed with law enforcement on Christopher Street. The uprising galvanized members of the LGBT communities to become leaders, to join forces with one another, and eventually to launch a movement that would change the course of American social, political, and economic policy.

One of those leaders is Ginny Apuzzo. She was raised in the Bronx, graduated with a BA from SUNY New Paltz and an MA from Fordham University, and would eventually go on to work in New York State government as well as the Clinton Administration. President Bill Clinton appointed her assistant to the president for administration and management, making her the highest ranking out lesbian in national government office. Apuzzo left this post in 1999 when she rejoined the National Lesbian and Gay Task Force as the first holder of the Virginia Apuzzo Chair for Leadership in Public Policy. In 2005, she was one of the founders of the Hudson Valley LGBTQ Community Center, and in 2007, Governor Eliot Spitzer appointed Apuzzo to the New York State Commission on Public Integrity, where she served through 2011. She lived for many years in Kingston, New York, before moving to Florida in 2013. She took time to speak with ACM by phone about her career before Stonewall, and how the uprising changed the course of her life.

The following is an edited transcript.

ACM: Take us back to that moment, to those six days of the Stonewall riots, and paint the picture of how this uprising changed your life.

Apuzzo: I was in the convent at the time. I knew that I was lesbian. I was twenty-six. I was in a new program that allowed us more latitude than your ordinary canonical novice has. I had heard about, probably read an article in the newspaper, about this uprising, and it’s as if it drew me – not the riot, but the act of rebelling. It just moved me, and in a few days, I did go to just be on the outskirts, to pass by, to be a witness to the feeling that was emanating from this event. I try to explain it like one can go to a place where something happened not for the physical details of the place but to absorb the feeling of it, and I kind of stayed in the outskirts of Greenwich Village and just looked around. Greenwich Village wasn’t a place that I was all that familiar with. I was drawn to it because a group of people decided they’d had enough. I think having been in the convent and having done some reading and studying, not just theological things but social phenomenon and theology and the notion that a group can rise up and break the code of silence around the agreed-upon notion that everything is fine.

I’ve since done a lot of reading about Václav Havel and the Velvet Revolution, and he writes that if everyone is in collusion with the lie then the smallest break in that shell has repercussions.

So, I had the sense of people having done this at such risk and such a courageous thing. I wanted to step into that atmosphere, a little like people who – like myself – went to the first and second Gay Pride Parades and stood on the sidewalk. You were there but you weren’t there, but it affected you.

So even though you weren’t necessarily on the ground during the riot, Stonewall impacted your life’s work.

Oh, yes. Stonewall pushed me over the edge, and by the early seventies I was involved in grassroots organizations. LFL–Lesbian Feminist Liberation, the Gay Academic Union, National Women’s Political Caucus in New York. I just kind of dove in. I happened to go along a political route taking on as a volunteer first at what was then called the National Gay Task force now the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force and volunteered to coordinate an effort to get the Democratic Party to create a gay rights plank in 1976.

The draft committee of the platform met in locales around the country. What I did was organize whatever local community existed. I learned to work with the local communities not in San Francisco and New York, but in Detroit and in Houston and in Cincinnati and in Phoenix. Stonewall and the various other early riots had begun to galvanize people, along with the local oppression by police departments of raiding bars and taking down license plates and entrapping people in male bathrooms, and the violence.

People were upset, people were willing to take a risk, they were organizing, and there were issues. Real issues.

In his speech, “The Other America,” Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. said, “a riot is the language of the unheard.” Here you have a leader who was a proponent of non-violence with this nugget within his speech that speaks to rioting and seeks to explain why these uprisings happen. What do you make of Dr. King’s assessment – that riots are the language of the unheard?

If I were to speculate, I might come to the conclusion that given those political pressures in the larger African American community at the time, he was giving cover to those people who were inspiring others to be heard. Dr. King’s assessment was as much an indictment of the people who precipitated the riots as it was of whatever damage was done. A message is not just a message for the listener but also the larger audience that may choose not to listen now but there might be an opening, there might be grace in hearing it.

What if an uprising is violent? Most people who have ever been on the margins themselves can get behind the idea of an uprising, but it seems that when civil disobedience turns violent, it gives people pause.

I don’t happen to think that violence is a means. I think non-violence speaks so much louder than the initial violence itself. I think those kids who integrated schools, for example, clearly knew it was dangerous, clearly knew it could precipitate violence, and that’s the courage of the moment. That’s what the moment calls from you.

It sounds like you’re saying that you believe that the uprising, whether it’s violent or not, is an effective tool.

Yes. I do think an uprising is an effective tool. And there isn’t violence unless the authority reacts to the nonviolent uprising in a violent way. I’ve been in many, many demonstrations. We never went in looking to hurt anybody, but the resistance to our issues precipitated something, and my feeling is if the authorities don’t have the control, if the people in charge, or if the people who are resisting this nonviolent uprising resort to violence, the outcome is on them.

You have been on the ground protesting many issues over the years. Is there one event, one movement that comes to mind that you felt was pivotal for you or perhaps has always stuck with you?

The AIDS protests. I was very involved during the AIDS epidemic both in government and in organizations. I went into the Mario Cuomo Administration about 1985, having been executive director of the National Gay Task Force. I learned a little bit about how government works. And the AIDS epidemic really pushed me to speak very clearly and distinctly to the governor. While I worked for him and I was loyal to him, the best way I could serve him was by serving my community, and that meant getting knee-deep in what was going on. So, I was allowed to protest. I actually was, by many in the administration, encouraged to utilize whatever stature I had in my community, as well as help to organize New York State within the government to be responsive. And there were many demonstrations and many contentious encounters, and sometimes they frightened me and sometimes they inspired me to keep at it.

Since the 2016 presidential election, many would argue that the country has been socially fractured. In this current political climate, many people have taken to the streets, some for the first time, whether for the Women’s March, Black Lives Matter, students protesting the proliferation of guns in our country. Are uprisings working today?

The questions for me are, Where have we come and how have we done it and where are we going and how will we do it? As a community we are at our best when we use the power for the common interest. And my feeling about that couldn’t be more emphatic.

When we found economic things that were discriminatory – in banking, for example, you couldn’t get a mortgage if you were gay or lesbian in the ’70s, you couldn’t get insurance on a house, you didn’t really exist to the larger authority, and so that made organizing on the local level so critical. In the late ’60s, ’70s and even the ’80s, we were so intent on getting government off our backs that we didn’t realize that there was so much more government needed to do. We had pounded on that wall, but we didn’t have a notion of what was behind the wall. And what’s behind the wall is an opportunity because behind that wall are people.

As the head of the National Gay Task Force, I secured social security benefits for persons with AIDS from the first Reagan administration because there were people behind the wall.

Margaret Heckler was head of Health and Human Services in the Reagan Administration. She rejected a proposal that we sent to her for one hundred million dollars to be budgeted for AIDS. And I developed a relationship with her number two, a guy by the name of Dr. Edward Brandt Jr., a Republican from Oklahoma. We got to be associates and gradually he came to see the absurdity, the utter absurdity, of the President of the United States not ever mentioning the largest public health crisis of our time.

There was a person behind that wall and your job often is to find that person who will grab an opportunity to do the right thing. You educate the person, support the person. And it’s worked so many times. There’s always work, but it’s another option when you’re looking to create a change.

The fact of the matter is that we have to be heard. Dr. King is right – we have to be heard. It’s our responsibility as human beings, and if not for ourselves for other people. Some don’t get involved and say, “Okay. I will live my life in this corner.” Not good enough. Not good enough.

✶✶✶✶

Tamika Thompson is a writer, producer, and journalist. She is co-creator of the artist collective POC United, and fiction editor for the group’s inaugural anthology, Graffiti (Aunt Lute Books, 2019). Her fiction is forthcoming in or has been published by Prairie Schooner, Glass Mountain, Literary Orphans, The Matador Review, Orca, and Huizache among others. Her non-fiction is forthcoming in or has been published by The New York Times, Los Angeles Review of Books, The Huffington Post, MUTHA Magazine, and PBS.org. She received a Bachelor of Arts in political science from Columbia University and a Master of Arts in journalism from the University of Southern California. She lives on Chicago’s North Shore with her husband and two children. She previously published an essay in ACM.